Characters sweat a lot in Michael DeForge’s comics. Not the kind of flop sweat that traditional cartoon characters exhibit, with water droplets literally flying off the body in a halo formation, but beads of perspiration that cascade down the character’s face in such a plentiful supply that you sometimes wonder why there isn’t a puddle around the character’s feet.

What makes them sweat so much? Oh, you know, the usual. Your organs and flesh are slowly turning into leather and spikes. You had to join a secret mafia club in order to get your niece’s beloved clarinet. You’re an ant that’s overwhelmed by the meaningless of it all. You got infested with baby spiders because your weird kid brother insisted on wearing that dead horse head all the time. You’ve been consigned to a hell populated by beloved cartoon characters. You’re a hapless, divorced flying-squirrel dog trying to deal with your own inadequacies and two unruly kids. You’re desperately trying to fit in. You just killed someone.

Throughout his brief (thus far) career, DeForge has explored issues of adolescent longing and angst, sexual and gender confusion, and the individual’s role in a seemingly uncaring — and at times hostile — society. Not uncommon themes, but DeForge’s sublime hat trick is to explore these motifs within horror, sci-fi, and fantasy frameworks, adding layers of discomfort, surrealism, and moral ambivalence to these tried-and-true archetypes.

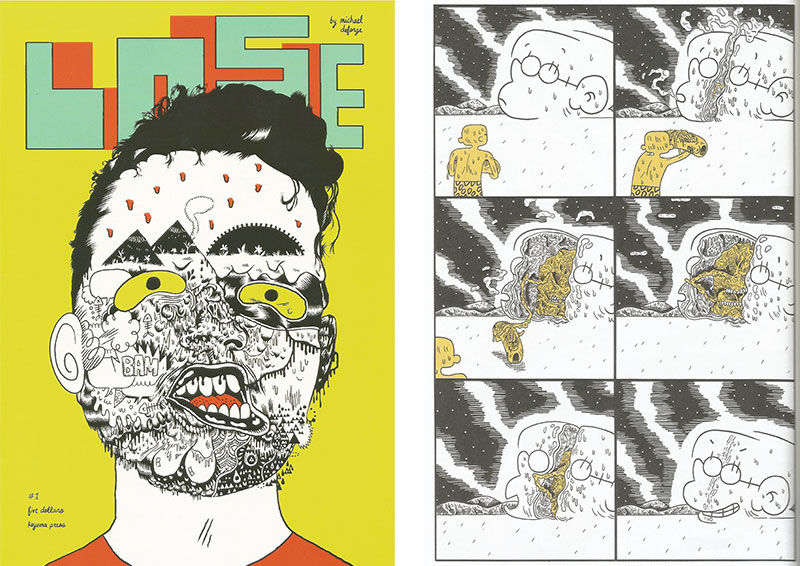

The cover to Lose #1, DeForge’s ongoing one-man annual anthology series and more-or-less his official debut (in 2009, now long out-of-print as DeForge has dubbed it “a bad comic book”), is ostensibly a self-portrait, but one that breaks down into various cartoon iconographies as the lower half of his face is littered with word balloons, topographical symbols, and outright abstract images. It looks as though his visage is melting or breaking out into some horrible rash. Or both. Francis Bacon by way of Mort Walker.

Consider that image a harbinger of things to come. DeForge loves playing with familiar cartoon shapes and patterns, squeezing and distorting them ever so slightly so that what should be cute or amusing somehow comes off as unsettling and “not quite right” (his dogs seem to consist of two circles for eyes, two ovals for a mouth, and sharp, pointy triangle teeth). Many of his early stories featured well-known comic strip characters like Nancy or Dilbert involved in odd or horrible goings-on. In the short story collection Very Casual, a caveman delivers a freshly killed offering to the enormous head of Jason, the annoying kid from Foxtrot. The head then proceeds to split in half, revealing a mass of wriggling tendrils and grotesque viscera lying just beneath the banal, smiling surface. Draw your own analogies.

In his more recent comics, DeForge’s art has even become more minimal and geometric. He seems to be trying to see how much he can subtract from a figure or object and yet still retain its Platonic form. At the same time, he has refused to adhere to one specific style. In Dressing, a more recent short story collection, he jumps about from one approach to the next — abstract forms here, profile cutaways there, impossibly elongated figures over here, cartoonishly ridiculous big heads and noses over there — DeForge seems to be deliberately challenging himself to not fall into some sort of codified style, which makes is art both instantly recognizable and constantly fluid.

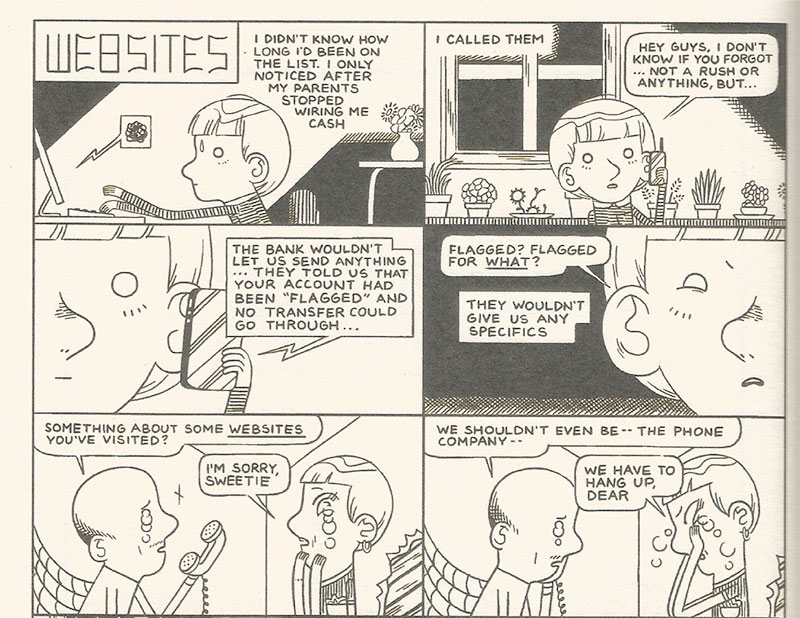

That fluidity extends to DeForge’s stories as well, where your social status, familial relations, and even your body can shift without warning in nightmarish fashion (DeForge is the master of the abrupt left turn). In the Kafkaesque “Websites,” a man finds himself completely cut off from society for reasons unknown (all he is told is he visited “some websites”). Even his parents aren’t allowed to speak to him. Only through a random occurrence that alters his visage is he able to reenter society and find greater success than he had in his previous life. In “Movie Star,” an ailing man discovers he has a twin brother, a wrestler turned action movie star. The pair’s lives converge until even his put-upon daughter can’t tell the difference between the two.

But it’s the human body and its promise of continual change (or eventual breakdown) that seems to fascinate DeForge the most. Whether it’s disease (as in The Sixties, where every animal in a small town — even the worms — has acquired the face of a young girl), survival (in Mars Is My Last Hope, a group of astronauts transform into an alien planet’s fauna, losing memories and language in the process), genetics (Incinerator depicts a young man whose torso is the back of Snoopy), or supernatural (in the x-rated College Girl By Night, a full moon turns a young man into a … well, you know), in Deforge’s universe, the flesh is not only weak: it’s mutable.

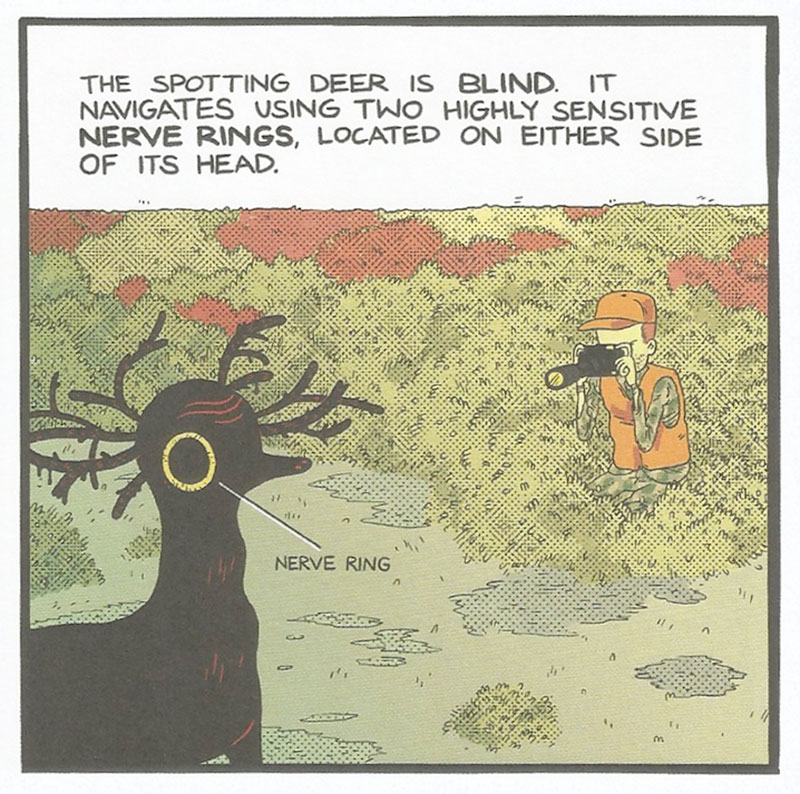

That mutability and strangeness extends to the rest of DeForge’s cosmos, which is filled with bizarre creatures and odd social structures. Spotting Deer is a Mutual of Omaha-like study of an animal that turns out to not be a deer at all, but a slug with “parasitic polyps” serving as antlers (that’s the least bizarre thing about it). In Canadian Royalty, DeForge creates an elaborately structured aristocratic lineage whose rules go from the bizarre to the outright ludicrous (the royals are in charge of such events as “the annual Ontario peeling ceremony”). Cody imagines a burgeoning underground movement that seeks to turn littering into an art form.

Operating in these surreal and often hostile worlds, DeForge’s protagonists rarely make admirable choices. In fact, they often come off as selfish, self-absorbed, or perhaps just a bit too needy. The lead character in Living Outdoors is a clueless teen who betrays a friend and endangers his life out of lust and a desperation to seem cool. In Recent Hires, the narrator has himself shot in order to win his girlfriend’s sympathies. The ants in Ant Colony are, almost to an insect, neurotic messes (one is an outright psychopath). Sensitive Property features a former activist who now works for real estate companies infiltrating and defusing protest groups. In short, DeForge’s characters are often capable of the same callousness and cruelty that is inflicted upon themselves by society at large.

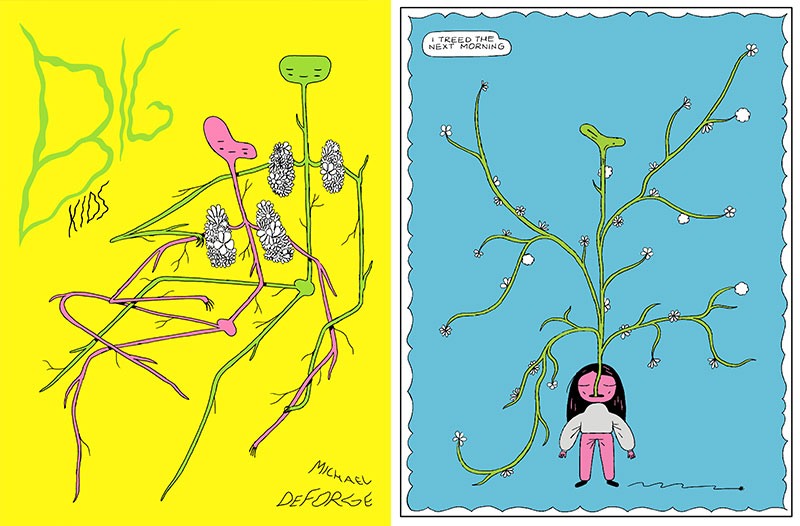

All of which brings us to Big Kids, DeForge’s latest work, a pocket-sized, square-bound graphic novel from Drawn and Quarterly. Despite its small size, Big Kids manages to hold just about all of the ideas and themes DeForge has been exploring up to this point. The secret societies, the adolescent angst, the strange body transformations, the antisocial hero desperate to find acceptance — they all coalesce in this slim book. If you were looking for a starting point in DeForge’s bibliography, this might be the place.

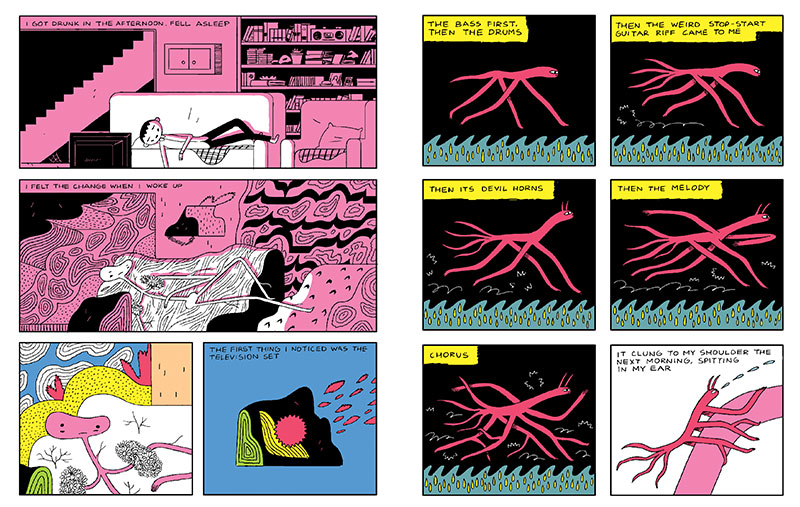

Big Kids is narrated by Adam, a bullied, closeted high school student who seems at first to be drifting through life in the way many of DeForge’s characters initially do. Then, suddenly (serious spoiler alert) Adam wakes up one morning to discover that everything has quite literally changed. His body now resembles an elongated pink stick, with a kidney-shaped head and flowers for lungs. Common devices like television sets and silverware have taken on odd, abstract shapes and glow with color and energy.

Turns out this is what the world ACTUALLY looks like. Adam has “treed,” a inexplicable maturation process that only happens to certain people, seemingly at random (though usually during adolescence) and features enhanced senses (to put it mildly). Those that don’t tree, like his father, are known as “twigs” and remain in the dark about the true reality of the world.

At first Adam revels in new discoveries. Sounds and smells take physical form. Music becomes a wiggly, multi-legged animal that clings to his shoulder. Swimming pools act as soothing respites that provide the chance to contort into mind-bending shapes. He even finds a new lover, another recently “treed” youth, and a new height of sensuality along with it.

But dissatisfaction and melancholy haunt the edges of this transformation. In fact, there’s a distinct suggestion that having the curtain pulled back for you only induces regret. The family’s boarder, April, is Adam’s initial guide to the world of “tree life.” But she’s also working on a computer program that would show what the world looked like before her transformation (“to remind us of the old shape of things”). Upon seeing a virtual version of her original self, Adam’s mom’s explodes in tears that crash through the house and lead to an irrevocable decision.

More to the point, enlightenment does not necessarily make you an enlightened person. In fact, discovering you’re one of the “special few” can lead to awkwardness, contemptuousness, and cruelty. That a change in perception does not automatically “fix” things. (Again, draw your own analogies.)

It’s that ambiguity between tree and twig, between discovery and disappointment, that makes much of Big Kids — and DeForge’s work in general — so compelling. In exploring themes of change, alienation, and maturity, but doing so in such a surreal, fanciful, and occasionally horrifying manner, DeForge is able to articulate painful truths about adolescence, adulthood, and the path between that sidestep cliche. We live in a world of wonders, but danger and destruction lurk around every corner. We can transform our bodies, genders, and identities but still remain fundamentally miserable. Change is constant but not always wanted or needed. We have the ability to transform our lives but often become preoccupied with petty grievances and mundane anxieties. Despite the hostility they often face outside their door, DeForge’s characters are often their own worst enemy. No wonder they sweat so much. •

All images ©Michael DeForge.