What is so American about Edward Hopper?

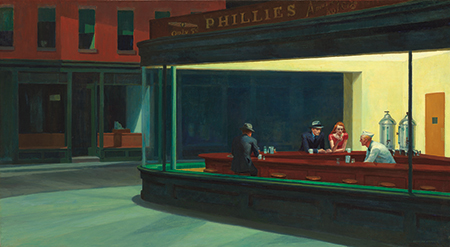

This is the question I pondered at this huge retrospective of his work in the heart of Paris. There seems to be a Hopper retrospective ever few years or so in the United States. His images have become so familiar, so iconic in their simple compositions and their isolated characters sitting silently in public and private spaces. His most famous painting, “Nighthawks” (1942), has been reproduced and caricatured so often you are surprised when you actually stand in front of it, the dramatic contrasting light between the diner’s inner, yellow hues and the shadowy street never match a reproduction. The painting practically glows from the interior outward, the light indistinct in source. It seems as if the whole canvas must be illuminated from behind. “Nighthawks,” like many of his works of the era, have become iconic of the mid-century era, their compositions inspiring artists and directors in the decades since. Hopper himself has from his earliest shows in the 1930s been called a definitively American painter, a painter who somehow captures the American scene.

- “Edward Hopper.” Through January 28, 2013. Grand Palais, Paris.

Take the review of Hopper’s first major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1933 in the New York Times, which noted with near glee, “on the ground floor are the water-colors — all of them save an amusing little set of Parisian ‘types,’ which has a wall to itself elsewhere in the building.” The “amusing little types” that captured scenes of Paris were by choice set off on their own, displaced as a kind of exotic moment amidst a landscape that was firmly American. In the substantial catalog to that show, MoMA director Alfred Barr argued that like any great artist of any era, Hopper traveled to the art capital of his day: Paris. But, Barr reassured, “he returned to his native country and showed in his mature work almost no vestige of his studies abroad.” In this way, critics often placed Hopper alongside the regionalist painters of the era such as Grant Wood or Thomas Hart Benton. These latter, mid-Western artists affected a rural idealism in their persona and canvases (despite the fact that Wood himself studied in Paris in the 1920s).

“Nighthawks” (1942)

Over two decades later, Time magazine, which featured Hopper on its cover, used the artist’s work and life as a crucial example of the kind of art that was uniquely American. In a tone that reflected those hyper-nationalistic 1950s, the profile celebrated Hopper’s own kind of realism and presented the artist’s work as important to the heritage of American art as distinct from European aesthetics. Over the decades, American art, the magazine informs us, “has reflected not European painting but American life — rough and smooth, tumultuous and diverse.” With respect to Hopper himself, the article quotes realist painter Jack Levine who noted “no dreams of the old masters set him off his course … Hopper looks inland. He’s an American painter all the way.”

“Gas” (1940)

Hopper’s Americaness has so often been his story, despite the fact that he himself was quite dubious of such a label. “The French painters didn’t talk about the ‘French Scene,’ or the English painters the ‘English Scene,’” was Hopper’s usual response to claims of his art’s geographical specificities. His rightful resistance to the claims about his art was an effort to recover his paintings as something more personal than national, more individual than social. “What lives in a painting is the personality of the painter,” he once said. And in this sense seeing Hopper as a kind of quintessential American painter distracts us from seeing Hopper the painter.

Despite the many times I’ve encounter his paintings, I’ve never had the experience of looking at Hopper in Europe. I hadn’t imagined that it would be much different than looking at Hopper in New York or Los Angeles. Unlike my earlier encounters with Hopper exhibitions, this one was not born in the United States nor was it set to tour there. Curated by Didier Ottinger, Chief Curator for the Centre Pompidou in Paris, “Hopper” at the Grand Palais offers a different story of artist’s development that has little to do with the American scene, and much more with the complex history that the artist’s work was caught in, between New York and Paris, between 19th century realism and 20th century modernity.

We can easily forget that much of what we admire about Hopper’s work today was done later in his life. The MoMA show in 1933 was mounted just before the artist’s 50th birthday. Between his art school education at the turn of the century, to the early 1930s, Hopper had worked as a magazine illustrator (the covers are projected in large colorful slides in one gallery), he experimented with etching (many are on display here), and worked for a time with watercolors. A small collection of these watercolors are presented here illuminating his delicate skill with the medium, crafting scenes as stark and quiet as his later works, each absent of people with hints of voyeurism. He exhibited and sold a painting in the famous Armory Show in the spring of 1913 in New York that brought European modernist works to New York — most famously symbolized in Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase” (1912). Such a diversity of experiences makes it difficult to know where to start the story of Hopper, and where to located the origins of his aesthetics.

Perhaps we can start at the New York School of Art where Hopper studied between 1900 and 1906. There he was influenced by his teachers William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri, who advocated a social realism that merged the values of late 19th century French painting with the particular subject matter of an increasingly urban America. It is Henri’s paintings that we first encounter in this show, his darkly framed image of an art student and one deeply intimate portrait of Thomas Eakins, whom he much admired. This first gallery situated Hopper among his contemporaries such as George Bellows, Whistler, and John Sloane. Henri’s focused drew on European post-Impressionism by capturing scenes of urban street life. For this group of artists, like their French contemporaries, the subject of painting rested on the new realities of social life, of working-class saloons, of construction sites, train stations, and boxing matches.

But before you get to these painters, this show opens with the black and white film “Manhatta” (1921), a collaboration between painter Charles Scheeler and photographer Paul Strand. The non-narrative film captures a sequence of Manhattan moments, from ferry crossings to the top of the newly built “skyscrapers,” the camera angled on elevated train platforms and window ledges all presenting the wonderment with the city’s growing monumentality. These images are interspersed with lines from Walt Whitman poems, modernism’s linearity meshing with 19th century romanticism. But such a vision of the city stands in strong contrast to the realists that Hopper studied with, whose vision of urban life is much more intimate, eschewing the skyscrapers of modernity for the street life in the shadows. Hopper himself never painted a skyscraper, though he lived much of his life in Greenwich Village, underscoring the personal and psychological themes of his paintings against modernism’s grandeur. His canvases are firmly rooted in an intimacy of small moments, a theater of empty spaces and silent encounters, of country lanes and lighthouses, that almost push out the voices and clatter of the city’s upward thrust.

“The Sheridan Theater” (1937)

But perhaps the real start, as this show suggests, comes with his travels to Paris, between 1906 and 1910. In his stays in the city, he resisted the circle of expat artists and writers. He didn’t visit the well-known salon of Gertrude Stein on the Left Bank, to engage the conversations on modernism. He lived instead a kind of isolated life. Years later he recalled that he met with nobody in Paris: “I’d heard of Gertrude Stein, but I don’t remember having heard of Picasso at all. I used to go to the cafes at night and sit and watch.” Instead he spent his days at the Louvre learning “perspective from Degas,” as the gallery text tells us. He learned from Vermeer the use of light streaming through an open window. He enjoyed the simplicity of Albert Manquet’s river scenes, the outlines of trees and bridges pronounced through the use of light and shadows, the landscapes in details blurring into abstractions. This show confronts you with a number of Manquet’s works along with Degas and Pissarro that ask us to look at these works as crucial to how we might look at Hopper’s use of light and his compositions. It was the light of the city, and the ways painters like Monet made light the subject of the painting that most captivated Hopper. “The light was different from anything I had known,” he later recalled, adding, “The shadows were luminous, more reflected light. Even under the bridges there was a certain luminosity.”

“Morning Sun” (1952)

Hopper’s own paintings of his time in Paris reflect many of the themes he would continue to work on throughout his life. His “Interior Courtyard at 48 Rue de Lille, Paris” (1906) is a simple study of a window and doorframe, the white curtains sweep back revealing a darkened interior. It is a study of light and perspective, and how the two seem to shape each other. There is no life in this interior, just as there is no life in the many landscapes he painted around Paris, studies of Notre Dame and barges along the Seine. These works are explorations into ways light and shadow create forms. They are captured from a distance, and even when the subject is a small staircase, there is often something just beyond the subject that we can’t quite grasp. But the perspective that he would eventually develop, that slightly distorted realism, had yet to emerge.

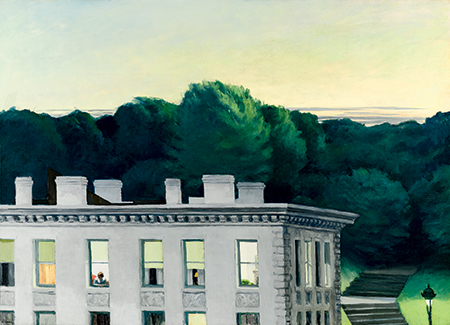

“House at Dusk” (1935)

It may not have been paintings that had the most influence on Hopper, as this show asks us to consider the stark Parisian photographs of Eugène Atget taken just a few years before Hopper was in the city. These streetscapes linger with a haunting presence and absence, buildings standing quiet surrounded by empty streets. “Hopper was charmed by the metaphysical atmosphere” of these images the gallery text informs us, and you see such influence in what would become Hopper’s obsession: The solitude of public spaces. In this sense these photographs presented Hopper with scenes reduced to objects, to the shuttered windows, the wooden doors, and cobblestones streets. Atget’s photographs are paired with those of Mathew Brady’s post Civil War images of the South, echoing similar depleted landscapes of buildings and objects, illuminated by the camera’s pure shadows and light that intrigued Hopper from the 1930s on. These images are projected life-sized on a large white wall, like a film or a doorway, as if you could walk into any one scene and emerge on the other side.

“The City” (1927)

After giving so much context, the show opens up and quiets down, leaving you with two large galleries of his oil paintings without wall texts or comment. The suggestion is clear: Paris taught Hopper how to see. As I wandered through these last galleries, I notice more acutely how his perspectives are distorted, buildings cut off half way as in “House at Dusk” (1935), the point of view floating in a nebulous realm as in “The City” (1927) or even how his interiors manipulate objects and light to create psychological realities as “Hotel Room” (1931). She could be one of Vermeer’s subjects who sits by a window reading a letter. There are many such scenes in Hopper’s paintings. Who is this woman who sits on a bed that has not been slept in (or has it been made already?) and reads a letter. We wonder about the luggage already packed, and why the woman is not dressed, and what the letter might be telling her. We wonder about the couple we spy on through the window in “Room in New York” (1932) and what they might be doing, his face set on the newspaper, her body twisted at the waist towards the piano, the whole room contorted as if pushing itself out the window for our voyeuristic pleasures.

“Room in New York” (1932)

What Paris gave Hopper was not only light but also an awareness of light’s psychological potential — but less so the natural light of open spaces than the artificial light of electricity. The relatively new electrical lighting illuminates so many of Hopper’s paintings, glows out of apartment windows, floods the interiors in indistinct ways. Hopper’s light inverts its usual meaning for insight and clarity. Rather, the light of his paintings betrays a kind of mystery and psychological density that remain distant. His many paintings set in theaters, unlike those of Manet or Degas, do not present the chaotic revelry between actors and spectators, but rather the quite moments before the show begins. The light on the spectators or on the lone usher standing near the exit makes the real performance of the theater these more personal and introspective realities that are just beyond our grasp.

“Hotel Room” (1931)

Hopper’s paintings so often gesture outside the frame of the image to something we cannot see but only wonder about. He gives us doors and windows to peer through, but leaves us to imagine the lives and rooms we look in on. What is going on here? Why are there no people on the street? Why is she naked? Where is she traveling? We look at his works with more questions than insights, and the light in his canvases hides much more than it reveals. To encounter Hopper’s paintings beyond their iconic aura, beyond the American geographies of hotel rooms, and apartment windows, of street facades and roadside gas stations, we can see how obsessed they are with turning privacy into a public spectacle, and public spectacle into mystery. As the poet Mark Strand has recently noted, standing in front of a Hopper painting “is as if we were spectators at an event we were unable to name; we feel the presence of what is hidden, of what surely exists but is not revealed.” I wonder if this too was something he learned in Paris, not from the paintings in the Louvre, but rather his wanderings along the streets and cafes of the city. If anything Hopper in Paris gives us a different insight into our idea of expatriate Paris in the early 20th century. Not everyone was having a party, or talking about modernism. Some wandered the city alone. In Paris, he explored an aesthetic of voyeurism and spectatorship that would become central to his paintings for the rest of his life. Hopper’s canvases present dramas without scripts, actions without stories, and scenes that are hauntingly more mental than material, turning these American scenes of solitude into alluring and enigmatic uncertainties. • 27 November 2012