Greek clocks do not waste but eat minutes. Greek noses, when curious, eat you. If Greek hands are hungry, you will soon get money, or be beaten. In Greece, too much work does not harm but eats you; you are not being scolded but eaten, you are not getting a boot but being eaten or even… eating wood (namely, getting beaten with a stick). Your head is not itching, but eating, and you are not searching thoroughly but are eating the world, hoping you won’t be eaten by the woodworm. Not only do you have to be aware of eating someone with your eyes, but also of not forgetting that in aging you are actually eating your own bread.

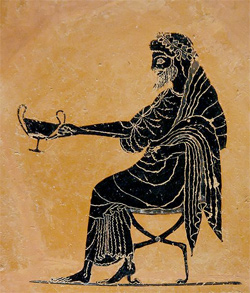

Ancient Greeks seemed to know the dialectics between language and food. Pindar offered food via his poetry. The thought of his lyric works as refreshing drinks and his melodies as sounding sweet as honey. Several literary species in classical Greece were expressed via cooking metaphors: satyr was the “sampler dish,” whereas the farce functioned as an interlude — “stuffing” amidst a serious performance. The general idea was that both books and men of letters were technicians producing pleasant mixtures for the mouth or the mind so as to satisfy the hunger of the word-eaters (lexifágos).

For ancient Greeks, “the beginning and the root of each good was the pleasure of the abdomen,” or, as Greeks today say, even “love goes through the stomach.” The ancient Greek “table” became the word for the Modern Greek “bank” (trápeza). Greeks still speak of the Epicurean feast, a sumptuous meal, and the Meal of Lucullus. They recall the famous symposia, the 30 sophists who sat around a dinner table to discuss a wide range of topics in the Banquet of Scholars by Athenaeus and “the dining philosophers problem,” which combine learning with… eating.

A central life concept, time (hrónos), is a word which etymologically relates to Kronos (Krónos). According to mythology, Kronos was the rather unaffectionate father of Zeus, who ate his children in an effort to maintain his authority. The great tragic poets of Greece attributed to Zeus adjectives such as caterer (trofodótis), alimentary (trofónios), fructuous (epikárpios), of the apples (milósios), and of the figs (sikásios). In addition, the word diet (díaita) stems from the Greek name for Zeus, namely, Días. Even the word nutrition, diatrofí, is a composite of the words días and trofí, thus, “Zeus” and “food.” In that context, nutrition is the proper diet, the one Zeus had, consisting of dittany tea (díktamo), honey (méli), and goat’s milk (gála).

Greek words may be sweet as sugar, coming out of a mouth as a river of honey. They may be silent as a fish or a pillar of salt, or calm as yogurt. When Greeks speak rudely, elders put pepper on their tongues. But when they get angry, they need to swallow vinegar. “Good appetite,” “To your health,” and “Good digestion” are frequently used expressions in Greek, absent from English. In a country where hospitality is lavish, village rules deem that one who enters the coffeehouse must treat those already present.

In Greek, “language” and “tongue” are one word: glóssa. “In the beginning was the Word”, the Lógos, something born in the mouth. The Annunciation is nothing else but a verbal conception: As the Virgin Mary absorbs the words of the Holy Ghost, she becomes pregnant and gives birth to Christ. Words, thus, using the human body and brain as transportation vessels are getting into the mouth and down the larynx to the pharynx and the esophagus, where they will be devoured and assimilated.

A closer look at the anatomy of the body tells us that Greek men have the Adam’s apple whereas Greek women continuously complain about their little breads and not…love handles. In general, Greeks grow almond trees instead of tonsils whereas they may get barley on their eyes (but not a sty). In their brains they have almonds — and not cerebellums — and on their skin olives — and not spots.

In the Greek worldview, bread (psomí, ártos) is a symbol of continuity and healthy life. Greeks pray for the daily bread. A Greek in a relationship is mature or convinced because he has been baked. To earn money, Greeks are making their own bread, sometimes even through sweating. Procrastinating is not blending the bread ingredients but continuing to sift. The hungry dream of bread loaves, and may even eat the tablecloth, whereas the greedy want both the dog fed and the pie untouched.

Synaesthetically, Cretans “hear” the smell and Greeks “flavor” colors: Tints may be of the rotten apple, the orange, the carrot, the eggplant, the cabbage, the plum, and the fish; the green of the olive, the cabbage, and the pistachio; the brown of the chocolate, the hazelnut, the coffee, and the cinnamon; the white of the milk; the cherry red; the yellow of the lemon, the corn, and the honey. When sunburned, a Greek looks like a dark-fired frying pan or pot.

Greek wine (krasí) is the nectar of gods. At the sounds of traditional music, Greeks open their wine barrels to festively honor saints such as Saint George the Inebriant, or merely to socialize and have fun. The grape (stafíli) is a symbol of fertility. “Wine and children speak the truth”, a Greek proverb says, whereas — inspired by the Aesop fable — “the grapes the fox cannot reach it calls them sour.” Ancient Greeks rarely drank wine waterless. Thus, krasí stands literally for wine mixed with water and the phrase “I put water in my wine” means compromising. Lastly, to a Greek, oínopas póntos, what Homer call the “wine-dark sea,” makes perfect sense.

Greece’s ethnic identity is recognized in its language. Bean soup is Greece’s national food. When beans insist on being raw, they behave like the country’s old-time enemies, the Turks. During Lent, bean soup reminds Greeks of sacrifice and restraint. This legume may be giant (gígantes) or black-eyed (mavromátika). Another legume, yellow split peas (fáva), may get married when mixed with onion and tomato, and, if you mash it and make a hole in its middle, then be careful, because there might be something wrong with or a hindrance in your life.

Speaking of condiments, salt is a necessary ingredient for human nourishment, and a symbol of duration, concord, and devotion. When Greeks throw salt to someone else’s plate, they are interfering into other people’s business. Stingy Greeks don’t even give you a grain of salt. Greeks who have eaten bread and salt together are like brothers and sisters. The family man is the salt of the household.

Fruits such as the pomegranate (ródi) and the apple (mílo) symbolize fertility. According to Greek mythology, the pomegranate sprang from the blood drops of Dionysus and symbolized Hades. Pluto, the god of the underworld, gave Persephone, Demeter’s daughter, a pomegranate to eat so as to remember him. Traditionally, Greeks would break a pomegranate in front of their doors upon reentrance to their houses on New Year’s for good luck.

The apple is a symbol of good luck, fertility, and fruitfulness. It symbolizes devotion of one partner to the other, particularly at weddings. It also stands for the acquisition of knowledge, heritage, and progress. As a Greek proverb illustrating Newton’s discovery and imaginativeness says, “the apple will fall under the apple-tree.” It is a purely erotic fruit. In Greek mythology, the apple-tree is the gift of the Earth to Zeus’ wedding. Paris offers an apple to Aphrodite as the prize of a beauty contest — the apple of discord. Its name is also associated with beautiful Milos, who hanged himself of a tree, when learned of Adonis’ death. Upon his death, Aphrodite converted him into a seed, which was named… apple (mílo).

Food expressions also mark Greek cultural ideals. The wise person’s children cook before they get hungry. The pot rolls around until it finds its lid. Too may cooks slow down the cooking process and spoil the broth. The guest and the fish stink after the third day. When a Greek brags about many cherries, bring along a small container, and if you get burnt at the pumpkin, blow even the yogurt.

On months whose names do not contain an “r,” Greeks must put water in their wine. Everything is seasonal, thus Greeks consume mackerel in August. Most Greeks have generous hearts as artichokes. Mean Greeks may profit fat out of a fly or milk out of the male goat. Old Greek women are rich in broth because they have eaten the sea by the spoon, whereas wealthy Greeks also own the bird’s milk.

You may think what I have been sharing with you is “zucchinis” (kolokíthia), squash words (kolokithokouvéntes) or vegetable marrow pies (kolokithópites). But I will teach you how many pears fit in the sack, so let’s call the figs, figs and the wash-tub, wash-tub. By the way, did you know that in ancient Greece figs were very important in cooking and whoever stole a fig from someone else’s tree was immediately accused as sikofántis (slanderer)? So, please, don’t hide behind the leeks, as I may catch you, and, as a Greek, dance you on the roasting pan.

Greeks do not put on layers of clothes, they instead dress themselves as onions. They are so hospitable; they may prepare a whole meal out of an onion only. Greeks should not eat like pigs, even if they are hungry as wolves. Eating light, as a bird, is best, especially with golden spoons.

Food is a basic societal need. As Greeks claim, “appetite comes by eating” and “if the pot boils, friendship lives.” Sharing a meal is the most common Greek social activity. Perhaps fast food was invented to house the lonely and to save them faster: The faster the process, the shorter the sense of solitude. We may drink alone, but food presupposes companionship, exchange of understanding. Perhaps that is why, unconsciously, Greeks always speak to their babies when they feed them: to accustom them to the sociality of food.

Take for example the Greek word nóstimo (tasty), which shares the same root with the word nostalgia. Nóstos means the return, the journey, while ánostos means without taste. Nóstimos, thus, is the one who, from the Homeric Odysseus to the contemporary Greek, has journeyed and arrived, has matured, ripened, and is therefore tasty and, in extension, useful.

I have tried to nibble on this spicy, meaty, juicy honey of a topic in order to savor and relish. I asked you to feast your eyes on the veritable potpourri of mushrooming food expressions that grace the table or Greek language and season your tongue. As I chewed the fat about the food-filled phrases that are packed like sardines and sandwiched into everyday Greek conversations, I tried to sweeten the pot with some tidbits of food for thought guaranteed to whet your appetite.

In that case, I don’t need to eat my words. (Otherwise, I’m ready to eat my hat.) After all, Greeks speak what they eat, and their big fat Greek vocabulary could make Greek a piece of cake! • 13 November 2009