The auditorium was filled with men, mostly between the ages of 60 and 70. Despite gray hair and widening girths, they were as giddy as teenagers. The occasion was a conference celebrating the 75th birthday of Superman at the Center for Jewish History in New York City. For those of us not part of the demographic, the scene appeared bizarre — all these old men communally regressing to their 13-year-old selves, trading minutiae on how Superman’s outfit was made (from the blankets in which he was swaddled when sent to Earth from his native Krypton) and on the five kinds of Kryponite (green, red, gold, blue, and white) and their respective powers (I forget). There were spirited conversations on favorite Superman narratives, with the focus on material from 1938-1969, the so-called Golden and Silver Age of comics. Anything after that, those in attendance agreed, was a falling off — second-rate, Bronze Age stuff that younger, more callow enthusiasts might go in for but at which they, being purists (which is to say, old), turned their noses up.

Since the site was the Center for Jewish History, it was inevitable that the keynote speaker, Larry Tye, author of the 2012 Superman: The High-flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero, would broach the not-altogether-novel topic of whether Superman was Jewish. A number of points were attested to in favor of this theory:

1) Superman was created by Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, two Jewish boys from Cleveland.

2) Superman’s name on Krypton was “Kal-El,” which means “Voice of God” in Hebrew.

3) Superman was sent to Earth as a baby by his parents to save him from destruction; he was adopted by people not his own. This was like Moses, sent out in his basket to escape death and plucked from the bulrushes by the Pharaoh’s daughter.

4) “Kent” could be an Americanization of “Cohen” — though I have to say that there are no Kents in my family.

5) Superman in his disguise as Clark Kent sought to assimilate into American life, much as Jewish immigrants of the time tried to do.

6) Clark Kent, with his studious demeanor and thick glasses was, let’s face it, the embodiment of a Jewish stereotype of the period.

7) The destruction of the planet Krypton can be taken as a metaphor for the destruction of European Jewry during World War II, occurring near the time that Siegel and Shuster launched the series.

8) Man is a popular suffix in a Jewish name. “Superman” has this suffix and can be pronounced to emphasize the fact — say Superman in the manner of Lieberman or Klingerman.

A student in the audience, who said he was writing his Ph.D. dissertation on Superman, presented some additional supporting details: Superman’s cape can be construed as a tallit; his spit curl as a displaced pais; and the triangle on his chest as half of a Star of David. The youth had more to say on the topic, but some of the old guys had had enough of the Jewish Superman and were ready to launch a counter-argument.

“The enduring fascination of Superman,” an audience member with a gray ponytail explained, “lies in his universal appeal. He is nonsectarian: Any group can identify but no group can claim him as their own.”

“That’s what we were going for,” nodded panelist Jim Shooter, who had written many Superman stories for DC Comics before transferring to DC’s rival, Marvel, where he eventually became editor-in-chief (though without severing his primal loyalty to Superman).

There was much murmuring in agreement. It seemed that for many in the audience Superman was a kind of religion or, more accurately, a displacement of devotion to the God of their forefathers onto love for American popular culture — and thereby a path to assimilation.

Jenette Kahn, a former DC Comics editor-in-chief, observed: “Superman is a hero for whom absolute power absolutely does not corrupt.” Several participants noted that Superman presents himself in reverse of superheroes like Batman and Spiderman. His disguise is his everyday persona, while his undisguised self is his heroic self. “As a hero, he shows his face to us,” agreed Kahn.

Superman as Clark Kent in 1978.

The discussion began to roam more widely as Samuel Norwich, publisher of the Jewish Forward, pointed out the element of social justice embedded in the Superman myth. “He reflects the values of progressive democracy,” Norwich noted, “and the personal touch — no job too large or too small.” Norwich also pointed out the superhero’s continuing topicality: “We shouldn’t forget that he is an illegal alien.”

The question and answer period was lengthy — many in the audience were inclined to perseverate, seeing as they knew more on this subject than the panelists. Superman is a topic that can be parsed ad nauseum, once again suggesting his Jewish (i.e. Talmudic) affiliation.

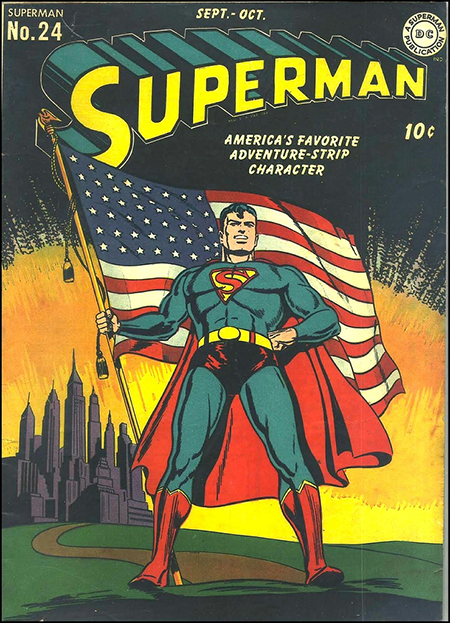

Superman in 1943.

After the program, the audience recessed to the Great Hall to inspect a glass case containing a 1938 photograph of one Stanley Weiss and, next to it, a sketch of Weiss by Joe Shuster. It seems Shuster met Weiss at a Jewish singles retreat and saw in him the image of Superman: “as he existed in my mind’s eye.” Weiss’s son, David, was present to recount the anecdote as told to him by his father. Given that David Weiss was a square-jawed Superman-ish-looking figure himself, this lent credence to his story.

Peering at the photograph and examining the hunky Weiss fils clinched it for some: Superman was Jewish, no two ways about it. Others, however, remained skeptical. The subject continued to be debated over birthday cake in the Great Hall, along with discussion about what a Golden Age Superman comic with a small tear on the front cover would fetch at auction. • 1 February 2013