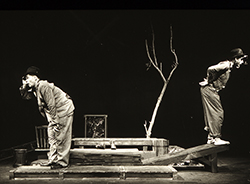

One of the legends surrounding Waiting For Godot (this year celebrating the 60th anniversary of its premiere) — and there are many, as is the case with all works of art that are mysterious and canonical — is that Beckett took his inspiration for the play from Caspar David Friedrich’s “Man and Woman Observing the Moon.” The painting is quintessential Friedrich: a subject — in this case two — gazing solemnly out at the sublimity of Nature. The man and woman stand on a hill next to a craggy tree that is half-dead, uprooted, and leaning over a rock. The couple is wearing traditional German folk dress. They are motionless, transfixed by the sky, the moon, the ridge of pines in the distance. The man’s arms are down; perhaps his hands are clasped before him. The woman keeps one arm at her side and her right hand rests gently on the shoulder of the man. “If there is one word for the mood of Friedrich’s pictures it is ‘longing’,” wrote the critic Robert Hughes, “the desire, never satisfied, to escape from the secular conditions of life into union with a distant nature, to be absorbed in it, to become one with the Great Other, whether that other is a mountain crag, an ancient but enduring tree, the calm of a horizontal sea, or the stillness of a cloud.”

Apparently, when someone once asked Friedrich what the couple was doing he replied, “These two are plotting some demagogic activities.”

“Man and Woman Observing the Moon” (c. 1830-1835)

You can see the similarity to Godot at a glance — two lone figures in a desolate landscape, a craggy tree, the moon. In “Man and Woman Observing the Moon” the two figures face away from us, they face away from each other — they are faceless. Faces, for the man and woman, are unnecessary. They are Rückenfiguren, figures seen from the back. They can see themselves only in what they see outside of themselves. It is not necessary to speak about what they see; it is not even possible. What Friedrich paints is the ineffable. Before the great glory of Nature, man and woman are mute.

Vladimir and Estragon, the two main characters of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot, are anything but mute. The two men can hardly shut up. Each time they face a moment of silence, a moment of pause, they panic immediately, fall into despair, hold each other fast and talk some more.

In the course of the play, we come to know that these men have been friends for around 50 years, and that they were told — when and by whom we do not know — to wait by the tree in the moonlight for Godot. They are poor; we don’t know why. As for Godot, we don’t know what or who that is either, only that Vladimir and Estragon are desperate to meet him, that they have been waiting for an undetermined period of time, and that they will continue waiting. Or they won’t. Waiting For Godot is not a play of answers. Like “Man and Woman Observing the Moon” it is a work of the ineffable, but an ineffableness very different than Friedrich’s. As they wait for Godot, Vladimir and Estragon fill the void with nonstop activity. They talk about the past, talk about the future, talk about the Gospels, exchange shoes, exchange hats, talk with strangers, contemplate hanging themselves from the tree, feed each other, play act, pretend to be the tree, exercise, sleep, sing, contemplate the moon, contemplate leaving each other. Each time Vladimir and Estragon try to make sense of their situation, try to understand it, control it, reason with it, they are filled with anxiety. It is the attempt to understand that gets them in the most trouble. “What we know,” says a character in Beckett’s novel Watt, “partakes in no small measure of the nature of what has so happily been called the unutterable or ineffable, so that any attempt to utter or eff it is doomed to fail, doomed, doomed to fail.” Vladimir and Estragon don’t know how to talk about anything without eventually being pointed to something unfathomable and inexplicable within their own selves. Every time they think they should know something, they talk and talk and talk and weep and cry until at last, dangling themselves over the abyss of the ineffable, they can only fall into an embrace.

ESTRAGON: Don’t touch me! Don’t question me! Don’t speak to me! Stay with me!

VLADIMIR: Did I ever leave you?

ESTRAGON: You let me go.

VLADIMIR: Look at me. (Estragon does not raise his head. Violently.) Will you look at me!

Estragon raises his head. They look long at each other, then suddenly embrace, clapping each other on the back. End of the embrace. Estragon, no longer supported, almost falls.

About Waiting For Godot more has been written, considered, thought through, guessed at, and reasoned than possibly any play ever — at least any play in the last century. In writing about the ineffable, about the failure of knowing, Beckett opened up a whole can of speculative worms. People have guessed the play is about death. That it is about poverty. That it is about war. That it is about concentration camps. That it is about Christianity. That it is about waiting — whatever that means.

I remember well the first time I read Waiting For Godot. I felt, when I finished, that I had read a very great love story, maybe the greatest love story I had yet read. At that time I hadn’t ever been in love, I was a teenager, but I felt all the hilarity and desperation in Vladimir and Estragon’s predicament pointed to something profound between the men — a noisy and inexpressible disastrously inextricable love. Among all the crying and the fighting, all the vaudevillian rearranging of hats, the one thing Vladimir and Estragon cannot stop doing is loving. Even when they stop doing, they are still loving.

How did these two men find each other? Why do they stay together? Even they do not know. Or, at least, they cannot say. Love is the ineffable. Beckett understood this. Love transcends reason. What we can say about love, what we think we know about it, is reasoning after the fact. As Vladimir and Estragon wait for Godot they wait to know, they wait to be told what to do, what they are supposed to do, what they are supposed to know. In the meantime, they are loving. Estragon asks of Vladimir, Who am I to tell my private nightmares to if I can’t tell them to you? And Vladimir says to Estragon, You’re my only hope.

When Beckett saw Friedrich’s painting that day in Berlin, and found inspiration for a play (maybe), he saw two figures with a deep longing, a never-satisfied desire. But whereas Friedrich expected his characters to find the sublime in (as Hughes put it) the Great Other, Beckett’s characters — godless and rootless and filled with dread every time they look at the moon and the tree — find the sublime in the Other. Or rather, in each other. We should turn resolutely towards Nature, says Estragon to Vladimir. We’ve tried that, replies Vladimir. True, says Estragon. Oh, it’s not the worst, I know, says Vladimir. What? asks Estragon. To have thought, says Vladimir. Obviously, says Estragon. But we could have done without it, says Vladimir. Que voulez-vous? asks Estragon. I beg your pardon? asks Vladimir. Que voulez-vous, says Estragon. Ah! que voulez-vous, says Vladimir. Exactly.

Vladimir and Estragon talk about escape. But they cannot. They are waiting for Godot. But why do they want to escape? And from what? From each other? To each other?

ESTRAGON: Oh yes, let’s go far away from here.

VLADIMIR: We can’t.

ESTRAGON: Why not?

VLADIMIR: We have to come back tomorrow.

ESTRAGON: What for?

VLADIMIR: To wait for Godot.

It’s almost as if Vladimir and Estragon wish they could be finished. What would it mean if they stopped waiting for Godot? But each day of waiting means another day of loving, which means another day of wondering, of chatting, of surviving, of thinking, of knowing and not knowing. Of waiting.

When we say that love is ineffable, as Beckett knew, what we mean is that, when we love, we don’t know what the hell we are doing. We can’t stop talking through it, trying to figure it out. We think we ought to be talking about everything, doing everything, doing anything — breaking into spontaneous rage, talking about suicide, playing games, complaining about our boots — instead of just loving. We wait and wait and wait. Inevitably, boredom creeps in, terror creeps in. When you give yourself completely to another, as Vladimir and Estragon have done with each other, and you say, “Don’t leave me, you’re my only hope,” every day is a little more and a little less frightening, every day is a little more and a little less suicidal, every day is a little more and a little less. You could, like Vladimir or Estragon, easily be talked into hanging yourself from a tree by the only one who could save you from it. We must escape. We cannot. We can’t go on. We do.

What’s your name? Pozzo asks Estragon in Act II. And Estragon replies, Adam. Are Vladimir and Estragon Adam and Eve? Is their love just as primordial? Just as new? Are all lovers Adam and Eve after the fall, wishing they knew whether they should keep on trying to get back to a prelapsarian state or move on?

ESTRAGON: You’ll help me?

VLADIMIR: I will of course.

ESTRAGON: We don’t manage too badly, eh Didi, between the two of us?

VLADIMIR: Yes yes. Come on, we’ll try the left [boot] first.

ESTRAGON: We always find something, eh Didi, to give us the impression we exist?

VLADIMIR: (impatiently). Yes yes, we’re magicians.

In love, Vladimir and Estragon make themselves and each other exist. They’re magicians. But they also have the power to destroy. At one point, while they wait for Godot, Vladimir and Estragon decide to verbally abuse each other, just to distract themselves. Moron! Vermin! Abortion! Morpion! Sewer-rat! Curate! Cretin! Critic! And then Estragon asks Vladimir, Do you think God sees me? — as if only Vladimir would know.

Basically, Vladimir and Estragon are terrified by their love. They cannot trust it for an instant. One moment, they are in terror of losing it. Of losing themselves in it. Then, they believe in it again, and are happy. And it goes this way, on and on. From the very start of the play, this relentless dance of terror and elation is apparent. They don’t trust each other. But they only trust each other. So there you are again, Vladimir says to Estragon, as if only he could know.

VLADIMIR: So there you are again.

ESTRAGON: Am I?

VLADIMIR: I’m glad to see you back. I thought you were gone forever.

ESTRAGON: Me too.

VLADIMIR: Together again at last! We’ll have to celebrate this. But how?

Yet maybe Vladimir and Estragon are terrified because they think they must know their love. And at the same time, they think that, if they figure it out, their love will no longer exist. They will no longer exist.

When we attempt to utter what we think we know, Beckett wrote, we are doomed, doomed to fail. Trying to talk about love may be the most futile performance of all. But just because words fail love doesn’t mean that love fails.

Samuel Beckett is not known for writing explicitly about love. But he was writing about love all the time. He wrote about love in his poem “Cascando”:

why not merely the despaired of

occasion of

wordshed

is it not better abort than be barren

the hours after you are gone are so leaden

they will always start dragging too soon

the grapples clawing blindly the bed of want

bringing up the bones the old loves

sockets filled once with eyes like yours

all always is it better too soon than never….…..saying again

if you do not teach me I shall not learn

saying again there is a last

even of last times

last times of begging

last times of loving

of knowing not knowing pretending

a last even of last times of saying

if you do not love me I shall not be loved

if I do not love you I shall not love

the churn of stale words in the heart again

love love love thud of the old plunger

pestling the unalterable

whey of words

terrified again

of not loving

of loving and not you

of being loved and not by you

of knowing not knowing pretending

pretending….

Love love love thud knowing not knowing pretending pretending if you do not love me I shall not be loved if I do not love you I shall not love — this is the song of all lovers, the song of failing, of being doomed. On the other hand, maybe we can be comforted by the fact that if we know we are failing, we also know we are loving. Just as Beckett saw in Friedrich’s painting; that which is ineffable can be sublime.

VLADIMIR: You must be happy too, deep down, if you only knew it.

ESTRAGON: Happy about what?

VLADIMIR: To be back with me again.

ESTRAGON: Would you say so?

VLADIMIR: Say you are, even if it’s not true.

ESTRAGON: What am I to say?

VLADIMIR: Say, I am happy.

ESTRAGON: I am happy.

VLADIMIR: So am I.

ESTRAGON: So am I.

VLADIMIR: We are happy.

ESTRAGON: We are happy. (Silence.) What do we do now, now that we are happy?

VLADIMIR: Wait for Godot. • 14 January 2013