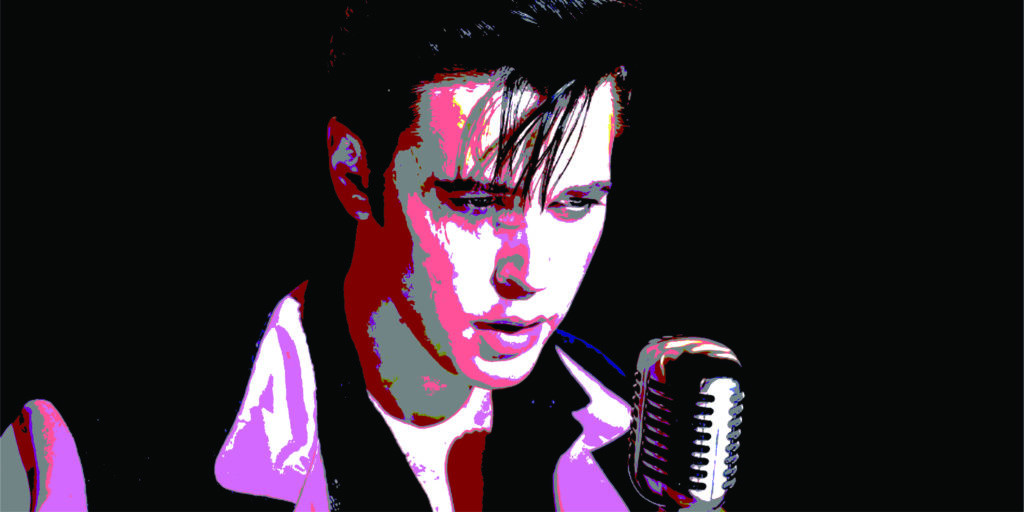

The opening chords of Elvis, Baz Luhrmann’s latest sprawling visual epic, are positively electrifying. Luhrmann layers image upon vivid image, superimposing and split-screening to his heart’s content —indeed, I wouldn’t be surprised if the first ten minutes managed to contain, on average, more than one fully-composed shot per second — in a vibrant build-up to the introduction of the film’s main act: Mr. Elvis himself, of course, whose thrumming tunes are underscored with enough ridiculous zooms on ecstatic audience reactions and subtly placed crotch shots to sway even the most detached viewer. Rendering the pure catharsis that surges in the energetic exchange between audience and performer, Luhrmann achieves no small feat, delivering in spades the primary desire of any audience member walking into the latest lavish, Hollywood-produced music biopic — to feel what it was like to be there when stardom was born.

How disappointing it is, then, that the film ultimately dissolves into the cinematic equivalent of a handful of discordant chords, leaving these surges of great thrill to float emptily in the wind. As I watched the closing act of Elvis, in fact, I was struck by the most alien feeling — namely, that I suddenly wasn’t sure what to feel. The flashy cuts and the closeups were all still there, yes, but they had lost their novelty and their footing, somehow. Sure, they were coupled with an odd musical flashback to Elvis’s youth but it, inserted hastily mid-song, came and went with little importance, presented as it was with absolutely no motivation whatsoever. Even Elvis’s character, I realized, had become totally alien to me: where usually I would expect some arc or development, I could see no clear change in the man before me, panting heavily on the stage as sweat dripped from his forehead onto the mic, except for the heavier makeup on his jowls and the flashier gems on his costuming — and even these visual changes were presented without comment. It was a profound existential crisis: had I lost my ability to watch and understand movies, I wondered? Everything before me had the trappings of emotional creation, but none of the actual sequencing or compulsion that would give them the appropriate weight or meaning to impact an audience.

I almost had to applaud the revelation of this sudden narrative abstraction, this total removal from identifiable plot structure. On the one hand, the film presents us with a laughably clear hero/villain opposition, with Colonel Parker (and his overdramatized, unbelievable narration) sketched as such a clear figure of unfounded, leering evil that even casting Tom Hanks, noted “lovable guy,” isn’t enough to complicate his role in the film. And yet, on the other, the film fails to follow through with any of these moral promises. With a constantly shifting narrative focus, always abandoning the present moment in favor of shinier, prettier baubles, the film becomes like a kaleidoscope in more ways than one: it’s both an orgastic explosion of light and color and an ultimately piecemeal, decontextualized object, consisting of opposing fragments whose simultaneous presentation only makes the whole thing all the more dizzying. Jumping from one narrative point to another and switching between locales, characters, and subplots ultimately serve only to jumble the film, exposing the emptiness that lies beneath this threadbare plotting. Even Austin Butler seems so enraptured in his task of portraying the screen persona of Elvis that he forgets to actually act, refusing to show any semblance of real emotion. Or, rather, the problem is that “semblance” is all he shows: even when mourning the loss of his mother with heaving sobs, he somehow manages to look pretty for the camera. All of the film’s attempts to extract narrative satisfaction in the back half of the film, as such, fail to stick their landing. From the moments surrounding JFK’s death to Dr. King’s funeral to Elvis’s own stand-off with Colonel Parker to any number of melodramatic monologues that crop up in the latter half, the final act is filled to the brim with uncomfortable tonal missteps —unjustified dramaticisms whose fraught repetition only makes them all the more tired and confusing.

In these ways, perhaps, the film is a lot like Elvis’s own career, itself waning and dully repetitive. Yet the film lacks the self-awareness for any such defense, instead blundering through all of these choices with an unmitigated earnestness. I don’t mean to parrot, to be clear, the too-easy argument of style over substance that this is slowly shaping up to be, especially not at a man like Baz Luhrmann, who can easily reply that that really kinda is, after all, the whole point of his directorial style. In fact, there’s something quite bold about so clearly prioritizing visual sensation above any clear perspective or thesis, and even something admirable in the almost cubist way in which the film constantly switches its perspective, refusing to stick with any emotional satisfaction, it seems, in favor of including them all. Yet it is the lack of consciousness with which this is all performed, from the empty visuals themselves to Butler’s blank gaze, that pull this film under.

It is this lack of self-awareness, in fact, that incriminates the film on an even deeper level as well, for it is this lack of awareness that allows the film to stumble into a fundamental logical fallacy: far from simply being an empty, confusing jumble of unsturdy filmmaking, it also becomes a confusing jumble that seems to partake in the very forces its villainizing — namely, those of stardom and the corporate Hollywood machine.

The movie, after all, so clearly posits the following as evil: Colonel Parker, and his predatory desire to leech off of Elvis’s art; Hollywood, and its false promises of meaningful stardom; the Las Vegas stage, and the temptations it offers of unmatchable grandeur (in the simplest terms possible: bigger as better); and the various shiny and enticing objects that Elvis buys, ultimately leading to his financial ruin. In turn, however, the movie also engages in the following: playing the energetic exchange between Elvis and his audience for sheer thrill, with a healthy dose of sexual voyeurism attached, all at the considerable price of 20 dollars per movie theater ticket; (most obviously) perpetrating the Hollywood machine, with a particular note on the star-making qualities of the biopic; striving to cram as much as possible into every single frame, both temporally and spatially (the opening five minutes alone contain more instances of split-screens, superimpositions, and close-ups than one could count); and prioritizing the glitz and glam of its aesthetics over meaning or narrative coherence. The film’s textual messaging is in direct contradiction to its subtext, placing the film at odds with itself.

Most importantly, this is all done with a few slight winks and nudges, but nothing close to actual satire or understanding, especially not when compounded with the film’s ultra-serious, sporadic bouts of botched family drama or equally botched political messaging. Even if the odd bone is thrown to satire via cheery ‘60s fonts and gleefully, ridiculously overdramatic narration, ultimately it does little to actually, definitively separate itself from the forces it blames for Elvis’s downfall. In yet another misstep of tone, the film can’t seem to quite commit to making fun of itself, furthering the confusion that I, hapless viewer of this three-hour epic, felt: not only is the piece untethered and emotionally confused, but it undermines what little aims it seems to have through sheer contradiction.

If there was any question as to whether the work is really taking itself as seriously as I claim it is — or if it is, also, as tonally deaf and confused as I sense it to be — the film’s odd, shoo-in ending should lay that to rest. Clips of the real Elvis play with an earnest seriousness as if performing a strange imitation of an in memoriam newsreel, while triumphant music soars in the background. The move equally touts him as the tragic hero of this story and engages in the exact type of false grandeur that it is supposed to hate; it is the most beautifully lukewarm “last nail in the coffin” that I could hope for.

In the end, it makes sense that a movie like Elvis happened: occurring at the tail end of a long string of musical biopic releases, all varying in quality (but largely they were all profoundly mediocre and unsatisfying), it is exactly the kind of weird sputter of powerful, but woefully misdirected creative energy to expect from a late genre release. All of this only serves to prove to me further that there is, ultimately, something inherently unsatisfying about the great genre of the musical biopic, exemplified here by the last energetic sputters left within the genre. Sure, Luhrmann (and many other directors who have been in his shoes) initially manages to serve up the very thrills that any regular audience seeks in such a great meditation on an artist’s life — the thrill of their performance, the anticipation of oncoming stardom, the great ability to go, “Gee, wasn’t that guy great?” — but the product always soon finds itself faltering. There is any number of myriad reasons for this tragedy, ranging from legal red tape and producer input to the promise of monetization as long as things don’t get too scandalous, etc. As the work of sensitive historical fiction that it is, the musical biopic is bound to the accuracy and objectivity of a documentary while promising all of the sensation and subjectivity of a narrative feature — two obviously rather incompatible aims. In many ways, perhaps, the genre is simply doomed, unable to keep up with the audience’s unceasing desire to experience fully the promised thrills of stardom. •