It seems as though every decade or era in alt-comics’ brief history can be marked by a flagship anthology. The underground comics movement of the late 1960s and ’70s was largely shaped by titles like Zap Comix and Arcade. In the 1980s, it was Raw and Weirdo that marked comics’ growing avant-garde. In the ‘90s, Drawn and Quarterly and Fantagraphics made the case for comics as art via D&Q’s self-titled series and books like Zero Zero.

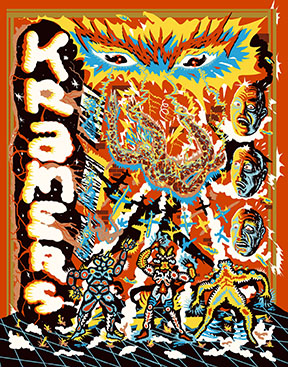

And then there was Kramer’s Ergot. Originally started by cartoonist Sammy Harkham as an outlet for him and his compatriots, the series turned heads with the arrival of volume four in 2003. Chunky and oversized, it introduced readers to a plethora of new cartoonists, particularly those that were a part of or were influenced by the brief Fort Thunder scene in Providence, Rhode Island, in the late 1990s.

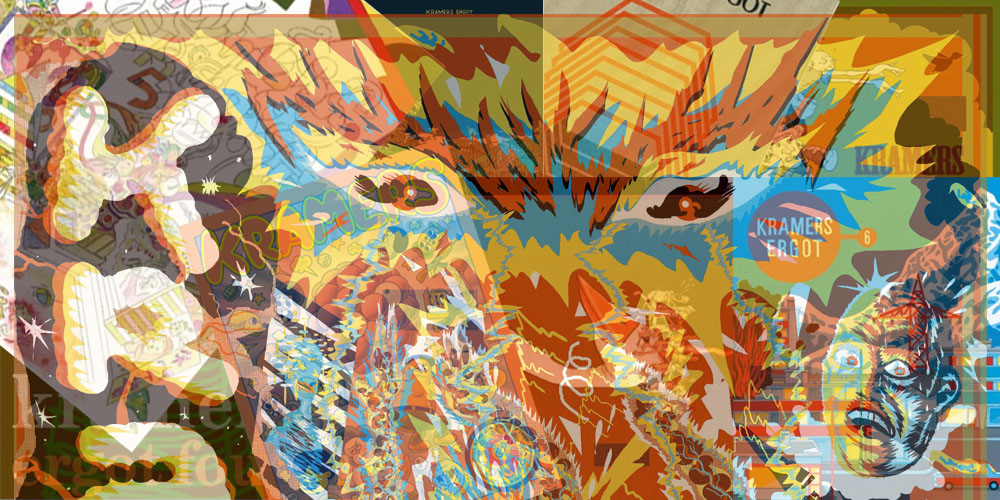

Harkham has continued to deliver a new volume every few years, occasionally experimenting in format and production — volume seven in 2008 was a ginormous (16″ by 21″) collection designed to mirror the size of early 20th-century newspaper pages. Now we have Kramer’s Ergot 10, one of the strongest volumes in the series in recent memory.

The contributor list for volume ten (or Kramer’s X if you prefer) has a rather impressive array of talent, many of them familiar to anyone who was reading indie comics circa 1999 — Robert Crumb, Rick Altergott, Ivan Brunetti, Kim Deitch, etc.

But what’s interesting is how short most of these established artists’ contributions are — a page or two at best — making room for some interesting work by lesser-known (at least outside of alt-comics circles) artists. (Crumb’s piece is surprisingly the weakest in the book, a sketchbook gag from 1990 involving a group of lizard-headed thugs who can’t seem to spray paint a swastika correctly and end up getting into fighting each other over their own ineptitude. The sequence obviously resonates given the recent rise of fascism but it lacks bite).

The strongest pieces here are ostensibly the longer ones, many of them from women. Anouk Ricard delivers a charming series of interspersed one-page gags involving a duck-faced cowboy and his whiskey-drinking, card-cheating horse. Anna Haifisch adapts a Mervyn Peake story about a rich art collector whose quest for the perfect addition drives poor, struggling artists to madness. Aisha Franz’s surreal “Malaparte II” imagines an island-dwelling man whose bourgeois comfort is rattled by the appearance of his peculiar neighbor. And Lale Westvind, who is quickly becoming a force to be reckoned with in comics, delivers a gruesome tale of a woman raised in the ocean and her first meeting with men. Westvind tells her story in dark hues of red and blue and diagonal slashes across the page connoting violence and lingering scars. It’s a tour de force.

Harkham has always cast his eye to comics’ past in Kramer’s, introducing readers to artists like Marc Smeets and Suiho Tagawa (Kramer’s 9 featured a lengthy segment to Ron Embleton and Frederic Mullally’s “Oh Wicked Wanda,” Penthouse’s BDSM-flavored answer to “Little Annie Fanny”).

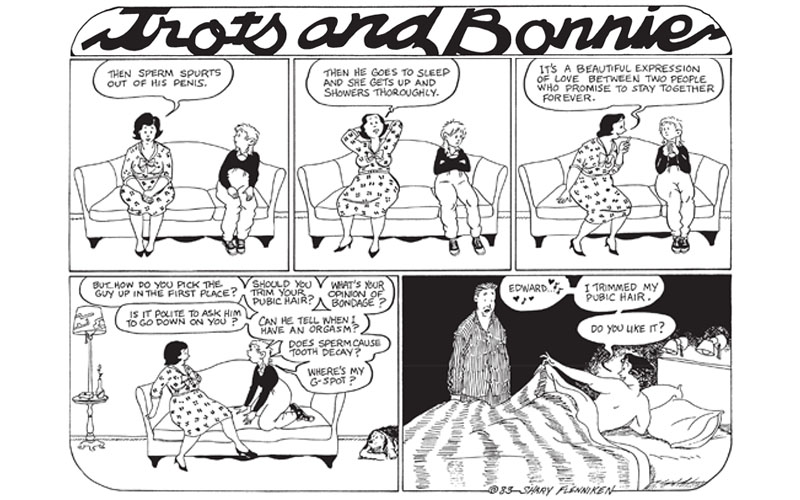

Here, it’s the great Shary Flenniken, an artist I’ve long felt has been unjustly ignored. Best known for the “Trots and Bonnie” strips she did for National Lampoon magazine back in the 1970s and ’80s, Harkham collects a small sampling here.

Reading these strips in an era where stories about sexual violence seem to be revealed every day, it’s kind of amazing how much Flenniken was able to get away with back in the day. Although drawn in a sunny style that connotes innocence, Trots and Bonnie is a deeply dark strip that jokes about murder, sexual assault, pedophilia in a deep knowing and acidic manner, where predators are around every corner. If anything, it’s a more shocking comic now than it was back in ’79.

The longest story in the anthology “and one of the best ” comes from Harkham himself. “Blood of the Virgin,” an off-short of sorts to the similarly-titled story Harkham is telling in his own series, Crickets. It’s about a young farmhand in 1915 who, enticed by the silent picture being made nearby, decides to head to Los Angeles to eventually find fame and fortune. Spartan in its dialogue, the story leaps across the decades to carefully unravel a story ultimately about friendship, betrayal and the bitterness that resides decades after.

What’s perhaps most fascinating about Kramer’s and this volume, in particular, is not just the diversity of talent but the way Harkham is able to connect each contribution so that the whole package flows together seamlessly, despite the plethora of styles on display. An over-the-top violent Johnny Ryan strip involving murderous convicts on the run is immediately followed by a colorful, psychedelic story by the artist known as C.F. Will Sweeney’s great sci-fi dystopia “The Big Embiggening” is followed by Helge Reumann’s bleak, apocalyptic “Equalizers,” which then leads to a comical rooftop via a 1922 “Gasoline Alley” strip by creator Frank King.

Kramer’s is no longer the place to go for what’s hot or new in comics (and truth be told, it hasn’t been for some time). What it offers instead is something a bit grander: a document of the seemingly limitless potential the medium offers. Look, Harkham seems to be saying, comics are both representational and abstract, direct and oblique, grim and adorable. Wanna know why comics are cool? Here you go. •