I could not get used to the windows in Classroom 3. They ran from floor to ceiling, lining the entire portside wall. The Pacific Ocean rolled by. Later, in other seas, there would suddenly be land when we weren’t expecting to see land, or The Voice would come over the speakers and announce the sighting of sea turtles, and we’d all have to stop what we were doing and run over to see for ourselves. After a week, the students had gotten better about not staring out at the wavering horizon; I still found those windows distracting.

“Help me close the shades,” I said, and began to lower the one closest to the podium. Collective groan. “Sorry,” I said. “We’re looking at slides today.”

I powered up the overhead projector. The ship rocked. I clutched at the podium. The first time my balance faltered, the students laughed; now it was just your standard, daily ship-rocking.

I led a discussion on Gauguin: “What do you make of Gauguin’s use of flatness and unrealistic color?”

“He’s exaggerating the primitiveness of Tahitian culture.”

“He’s trying to reclaim the innocence of the primitive people.”

“What do you make of this slide?” I asked. “Would that have been acceptable if Gauguin had used naked French women as models instead of the Tahitian women represented here?”

“Professor? We can’t really see.”

I walked in front of the podium and turned to face the screen. All the eye could make out were vague shadows of color. The sun was too bright — the shades couldn’t keep it out. We tried to adjust the shades. It didn’t work.

“So, the world outside is interfering with our classroom studies. Does anyone see a metaphor here?”

This was the fall 2006 voyage of Semester at Sea. I was one of three English professors on board. I taught three classes on the M.V. Explorer: creative writing, travel writing, and “Exoticism in Literature.”

We were 60 teachers and staff and 550 students, and we came from colleges and universities all over the United States. We traveled around the world on the fastest passenger vessel on the planet. (Top speed: 28 knots.) The ship was 590 feet long and weighed 24,300 tons. It was four years old, and it gleamed with fresh paint and the constant swabbing of the wooden decks. In 100 days, we sailed from San Diego to Florida, stopping for five days each in ten ports. The itinerary: Hawaii, Japan, China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Myanmar, India, Turkey, Egypt, Croatia, Spain.

“This is not a cruise,” the deans reminded us, repeatedly. “This is a voyage of discovery.” Semester at Sea might not have been a cruise, but one thing was certain: We were on a cruise ship.

•

This was the first time I’d teach Exoticism while traveling, and with students to whom travel might be a brand new thing. I’d taught something called “Exoticism in Literature and Art” for five years at Emerson College in Boston. I’d designed it around books I liked, contemporary art I liked, and Orientalist art I’d researched, because it was what most scholars identified with exoticism. The course had developed organically, out of my own experience traveling, and because of what I did with my travels, which was write about them.

Emerson students readily bashed certain artists, including primitivism in the work of Gauguin. They were arts and communications majors — young writers and filmmakers and set designers and audio producers. They were critical, jaded, lefty, and often funny:

“Yeah, Gauguin thinks he’s all back to nature. He forgot to mention in Noa Noa that all his food was canned stuff that came from a store.”

“He married a 14-year-old and they couldn’t even understand each other’s languages! That’s gross.”

Emerson students were also forming analysis from the relative comfort of their dorm rooms on Beacon Street. Perhaps, for instance, they’d read Tim O’Brien’s Vietnam stories differently if they were reading them in Vietnam.

I’d always been a traveler. I took time off from college for an 85-day Outward Bound “cultural exploration” course, which — in addition to teaching me how to survive in heavy rains, lost for two days, with a dwindling ration of soggy crackers and 14 people ready to kill each other — culminated in the ascension of a 17,000-foot volcano outside Mexico City. I left feeling tough. I spent a semester studying in Seville, Spain, living with a family. The nine-year-old, Ana, who quickly became my best friend, taunted me ruthlessly for language errors until my Spanish was almost fluent. At 22, I left the U.S. for Costa Rica as a volunteer English teacher. I lived in a one-road village in the highlands amongst coffee farmers and sugar cane cutters and hiked to school through muddy, cane-strewn fields. I became unfazed by the sight of lice. I went weeks without speaking English. Sometimes, while speaking with fellow Americans, I would switch from English to Spanish without noticing I’d done it. This was my idea of travel: I believed in immersion and effort. I believed a little bit of suffering wouldn’t kill you.

Traveling became my job. I led summer trips abroad. I slept on a concrete floor in Costa Rica for a month with ten American teenage girls, and helped the townspeople demolish a school and then build another one. At 30, I began directing an educational program for Americans in Cuba. We learned how to defy the oppressive “tourist Apartheid” in Cuba, and how to get money directly to the people as often as we could. We illegally hired music teachers, tipped in dollars, and bought black market ice cream. We spent our weekends in family-owned casas particulares instead of government-run hotels, eating in family-run paladars instead of government-run restaurants. The Cuba program lasted until the Bush administration killed it. I went to Cuba five times.

I wrote about my travels. I wrote short stories and travel essays and began a novel that will never be finished. I couldn’t quite get Costa Rica, in particular, out of my system. I wrote about my Evangelical host family; I wrote about quirky Costa Rican habits. I wrote about Costa Ricans I loved and the American tourists I did not love. One day, at a party, I met a Dominican-American writer whose work I admired. He asked about my writing and I told him. He asked me if I were Costa Rican. I said I was not. Not long afterwards, he said something that slapped me right in the face.

“People always want to write about us,” he said. “Like we’re the fucking anthropological study of the month.”

I panicked. My momentum, as a writer, halted. I became convinced I was doing something wrong by writing about a culture as an outsider. I was a condescending, imperialistic, ethnocentric…asshole.

No, I wasn’t. Wait. Was I?

So I read. I read novels by Paul Bowles, Isak Dinesen, Joseph Conrad, and Melanie Sumner. I read theory by Tzvetan Todorov and Edward Saïd. I found other writers who packed in local color and charming details and skimped on depth. I found characters who seemed to have forgotten the meaning of home.

To my relief, I landed at the logical: that literary exoticism — the presentation of one culture for consumption by another — was not always “bad.” It was, in fact, a way to promote cultural dialogue. The determining factor was how far outside her own perspective a writer, or traveler, would venture. It mattered where they’d gone, why they’d gone, and how they got there. It boiled down to how one traveled.

So, I developed this course, and went about using books to bully young college students into being responsible travelers. I believe that sometimes it worked. Some Semester at Sea students came on the trip to lie at the pool and get wasted in Kobe, in Cairo, in Ho Chi Minh City. But most of them were here because they wanted to understand the world.

But me, meanwhile. Look at this mud-covered, fluent-speaking, system-dodger now! Traveling around the world and stopping in ten countries just long enough to learn the words “hello” and “thank you” — then promptly forgetting them. Residing, for three months, on a cruise ship with a pool and a spa, in a cabin with a porthole, a king-sized bed, marble bathroom floors, and two closets. And a cabin steward (a cabin steward!) named Edwin, from the Philippines, who cleaned my cabin twice a day.

I even had an ice bucket. Who needed an ice bucket?

My feelings about this new me were mixed. I mean, it’s not like I was going to complain about circling the world on a ship. No one could argue that this wasn’t a dreamy way to travel. The real question was how to change my lens so that I could look at it as the right way to travel.

•

The ship stopped in Hawaii long enough to refuel. I led a trip to the Polynesian Cultural Center, which was more like a Polynesia-specific Epcot Center run by Mormons. All the scenery I saw inside the Cultural Center was fake. The “islands” — Tahiti, the Marquesas, Samoa — surrounded a fake lake. Even “Hawaii” was fake. Everywhere in between the “islands” were souvenir stands selling Hawaiian Barbie dolls, plastic leis, wooden masks, and woven hats.

The ship stopped in Hawaii long enough to refuel. I led a trip to the Polynesian Cultural Center, which was more like a Polynesia-specific Epcot Center run by Mormons. All the scenery I saw inside the Cultural Center was fake. The “islands” — Tahiti, the Marquesas, Samoa — surrounded a fake lake. Even “Hawaii” was fake. Everywhere in between the “islands” were souvenir stands selling Hawaiian Barbie dolls, plastic leis, wooden masks, and woven hats.

I sat with my student, Hilary, and watched dancers wearing chemically-dyed feather headdresses and carrying factory-made spears perform a Marquesan tribal dance. We watched the Marquesan MC coax four newly-wedded men onto the Astroturf stage, hand them spears, and instruct them to “kill the pig.” The tourists fake-stabbed at a teenage boy dressed in a pig costume made of dried grass and rope. They carried the dead “pig” away on a stake.

Now this was exoticism.

Hilary and I clapped and smiled.

“How exotic!”

“How charming!”

“They’re so primitive! It’s so genuine!”

“Gauguin would hate it here.”

“Yes he would, Hilary. Yes he would.”

We went to the Polynesian snack bar for lunch. We ate hot dogs and drank Diet Cokes.

Then we were back on the ship.

Climb the metal stairs. Spread your feet and arms apart; get frisked and wanded by security. Even your bra’s on limits for the frisk. Swipe your card in your cabin door, drop your bag, look for your friends, tell them your stories.

After Hawaii, the best stories going around were the ones about the students who got caught trying to smuggle alcohol onboard. Sneaky girls with small breasts, for instance, borrowed the bras of their large-breasted friends, and lined the bras with plastic baggies filled with booze.

After Hawaii, the best stories going around were the ones about the students who got caught trying to smuggle alcohol onboard. Sneaky girls with small breasts, for instance, borrowed the bras of their large-breasted friends, and lined the bras with plastic baggies filled with booze.

“Then, some kid brought on a case of water bottles, plastic wrap intact, and we almost let it get through. But then the security officer noticed that the lid on one of the bottles was a tiny bit askew.”

“Vodka?”

“Yup.”

“Busted!”

“Poor fools,” my friend Brian said. He opened his backpack and produced a double-tall bottle of cheap white wine.

•

The faculty/staff lounge was upstairs on Deck 7. Every night until eleven, Mag — from the Philippines — served up piña coladas and Tiger beer and bowls of cheddar-flavored goldfish. Early on, the young and the childless gathered nightly to figure out who their friends and travel companions would be, and to occasionally get somewhat drunk and sing karaoke.

Days, we were busy. When there weren’t classes, there were meetings. I spent my hour-long windows of free time on the elliptical machine at the gym, or grading papers in my cabin, wishing I could be sitting by the pool on Deck 7 aft among the students who baked in the sun, watching the frothy wake of our ship fading into the horizon.

Then I figured out I could grade papers at the pool.

I made friends with Kate, the charming administrative coordinator, and Brian, the videographer who read good books and cracked me up. Kate and Brian were big karaoke fans. We knew what we were doing in Japan.

In Exoticism, on our way to Kobe, we discussed Arthur Golden’s novel, Memoirs of a Geisha, and the film adaptation of the novel.

“White, Western author, writing about a Japanese geisha. Being forced into prostitution worked out pretty well for this girl. Realistic?”

“I loved the movie,” one student said.

“Me too!” several students said.

Ah, yes. Work to be done.

•

The ship cleared in Kobe and the Amazing Race began: The contest was to see who could see the most and the best of Japan in five days. We swiped our cards at the gangway, scattered. We were free of school obligations while in port.

In Japan, Kate and Brian and I spent a night at a ryokan on the island of Miyajima, wearing matching kimonos, eating delectable, unidentifiable foods in our own private dining room, and lounging in the baths. We took a train to Kyoto and biked around the city. Here is a picture of the silver pagoda. Here is a picture of the gold pagoda. Here is a postcard from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. We spent two nights at a karaoke club and sang until our vocal chords betrayed us.

In Japan, Kate and Brian and I spent a night at a ryokan on the island of Miyajima, wearing matching kimonos, eating delectable, unidentifiable foods in our own private dining room, and lounging in the baths. We took a train to Kyoto and biked around the city. Here is a picture of the silver pagoda. Here is a picture of the gold pagoda. Here is a postcard from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. We spent two nights at a karaoke club and sang until our vocal chords betrayed us.

Then we were back on the ship.

Climb the flimsy metal steps. Swipe your shipboard I.D. Enter your private square of the ship, that safe bubble of comfort. The door clicks behind you.

Once the ship cleared in Kobe, and everyone was back onboard, The Voice came over the loudspeaker. “Attention everyone. There will be an emergency meeting in the Union at 2000 hours. All must attend.”

We were having our first emergency!

In 2005, the Explorer had been hit by a rogue wave while en route from Vancouver to Japan. It was a dramatic disaster. Windows were blown out, engines were disabled; glass tables and cabin mirrors shattered. Students and faculty were flown to Japan while the ship was repaired. This was not one of Semester at Sea’s more reassuring legends. But it was an exciting legend.

At the meeting, they told us Typhoon Shanshan was heading right for us. It had been heading for Taiwan, then hooked towards Japan just before our departure. The Explorer was re-routing, they told us. We were skipping Qindao, China, altogether and going straight to Hong Kong. The crew put out baskets of Meclizine pills and soda crackers. Now this was traveling.

In bed, groggy from Meclizine, I stared at the ceiling as the sea lifted my bed, then dropped it. My stomach was in my throat. This was not fun after all. Something clattered behind the bathroom door. I rose, clawed at my bedcovers to keep from falling, and made it to the bathroom, where I removed from the sink my electric toothbrush, a bottle of hair-shine serum, and the glass pot of facial moisturizer that was somehow still intact. Everything went under the sink. The smack and thunder of the ship bucking on the water lasted into the next day.

A third of the seats in my Exoticism class were empty. People were locked in their cabins, throwing up; some could not wake up from the Meclizine. Those who did attend my class looked stoned and took an exam, applying theory to an essay by Seth Stevenson called “Trying Really Hard to Like India.”

“Sorry about this,” I said, handing out the tests. I bumped into walls. I knocked over a chair. I figured out how to get the timing right: When the ship pitches, you can jump into the air, and you’ll stay there — you can fly.

Because of the re-routing, I missed the Great Wall of China. I also missed Tiananmen Square. I wasn’t all that disappointed to miss these things. It’s a big world.

•

In Southeast Asia something shifted. It was easy to travel in Cambodia or India, easier than it was in modernized cities like Hong Kong or Tokyo — people were more open, transportation systems were more chaotic, diseases were more infectious, and standard rules of behavior were more likely to go out the window.

Also, things were cheap.

In Ho Chi Minh City, the SAS shuttle dropped us in front of the Hotel Rex, which we’d heard had been the hub for American GI leisure time during “The American War.” The market, blocks away, seemed like a logical place to start our explorations of Saigon.

Bartering fever diverted us. Street vendors, squatting on the sidewalk, used machetes to lop off the tops of skinned coconuts and offered us the whole thing with a straw. “One dollah!”

My instinct was to ignore them. But when we passed the third coconut vendor, already choking on Saigon heat and motorbike fumes, the juice started to look pretty good. Kate squatted to meet a vendor, a teenage boy in a greasy trucker’s hat, and attempted to trust him as he told her how much her dong was worth in dollars. He took her dong and we had our green coconut.

“How much did you pay for that?” asked a Semester at Sea student coming the other way, holding his own coconut.

“A dollar,” Kate said.

“You could have gotten two for a dollar,” he said.

Thirty minutes later I was lost in the maze of the indoor market, laden with plastic shopping bags. The original plan was to investigate the scene for later gift-buying, eat lunch, then head into the city. But then there was this adorable tea set, square black-and-turquoise cups with bamboo handles and a bamboo tray, for just $10. And then there was this silk bag I thought my sister would love — $4. The assistant dean, Roanne, rounded a corner and grabbed Kate by the sleeve. “You have to go to this stall,” she said, handing her a wilted business card. “They have the best silk, everything fits!” I soon had an ankle-length red dress, a black dress with red tubing, a yellow side-button top, and three gift scarves. Silk. Well-made. Fancy. $38 for it all. I could never have imagined bargains like these.

As we headed towards the exit, I stopped to examine a red, patent leather Gucci knockoff clasp purse. It was totally tacky, and though it was also fabulous, partially for its tackiness, I can’t say I really wanted to own this bag.

“Ten dollah.”

“Three dollars,” I said, without thinking.

“No, no. Ten dollah. Good price.”

We played it out. I walked away. I was yanked back by a lower price. The vendor and I pretended to become insulted and annoyed with each other. I looked down, and in my hands was the purse, wrapped in tissue paper. My wallet was $7 lighter. That’s when I knew I had to stop.

Later, when we discussed Vietnam in the context of Tim O’Brien’s war stories, I asked my Exoticism students: “What did you associate with Vietnam before you went there?”

“The war,” they answered unanimously.

“And now?” I asked.

Silence.

“Shopping?” I asked.

Laughter/muttered assent.

“That’s not what I associate it with,” one student, not laughing, said. “I asked this guy if he would take me across the river in this little wooden boat. He brought me home to meet his family. I made friends in Vietnam.”

Meanwhile, my creative writing students were beginning to generate some impressive work. I told Brian and Andy in the faculty/staff lounge about an essay one student had written about trying to get a massage in Vietnam without getting a hand job.

“That happened to me, too,” Brian said.

“That happened to me, too,” Andy said.

They were both visibly traumatized. “I don’t want to talk about it,” Andy said.

“Let’s just say it was a battle until the end,” Brian said.

•

Mid-semester, each Exoticism student gave a presentation about how they traveled. The assignment was based on the categories of exoticism delineated by Tzvetan Todorov: ethnocentrism, primitivism, and humanism. We’d used these to examine the literary texts and the accompanying art; now we were turning it around on ourselves.

We’d read Flaubert, partly, to knock him down. We’d criticized the way he exploited his French power to gain access to important people in Egypt. We criticized the fact that the only women he tried to meet during two years in Egypt were prostitutes. But we also watched him shift from Romanticism to Realism when he visited the Pyramids. We read about him running out of water while traveling with a caravan; he suffered. He acknowledged that he’d idealized the famous prostitute, Kuchuk Hanem. Was he an ethnocentrist? Because, you know, ethnocentrism was lame. And if he was an ethnocentrist at the beginning of his trip to Egypt, was he by the end?

Humanism was the “good” exoticist’s goal. To release your cultural assumptions, find some rational basis of judgment, and apply it as readily to your own culture as you would to another.

Hilary described her experience with pushy vendors at various tourist locales. “I found myself getting really annoyed. They were mean. One pushed me really hard when I wouldn’t buy a deck of cards. I realized I was getting angry, but I wasn’t thinking about what it might be like to rely financially on this tourist industry. At the time I didn’t stop to think what their lives might be like. I’m afraid I was really ethnocentric.”

Roger showed photos of a hike he took through the jungles of Vietnam. “The landscape was different from what I’m used to. I’d been in the woods, but I’d never been in jungle. I was fascinated, but I don’t know if that makes me a primitivist. I like to think that there’s a universalism to appreciating nature. So, hopefully, I’m a humanist.”

Most students found themselves to be a combination of two, or all three, categories. Here was the gist of the most common analysis:

“I want to be a humanist, but I know I’m an ethnocentrist. I think, if I’d had more time, I would have been more of a humanist. You just can’t let go of your own culture’s assumptions in a few days.”

We kept trying.

•

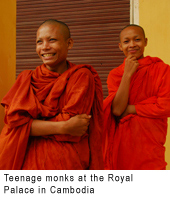

In Cambodia, I take a guided tour through the rooms of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, examining rusty tools of torture and watching Semester at Sea students cross the line into doom. A guide explained the Cambodian autogenocide to us — few students had heard of the Khmer Rouge, or the Killing Fields — how the Khmer Rouge had tortured, forced into labor camps, and murdered somewhere between 850,000 and three million fellow Cambodians in four years. The effects of the autogenocide were fresh. Everyone we met had relatives who’d been killed; no adult seemed to have a father. At the National Museum, I took pictures of two teenage monks, and when they saw me aim the lens at them, they came over to view their images in my digital camera’s display. We talked, using sign language, for what seemed like an hour. I watched the sun set over the Mekong River.

In Cambodia, I take a guided tour through the rooms of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, examining rusty tools of torture and watching Semester at Sea students cross the line into doom. A guide explained the Cambodian autogenocide to us — few students had heard of the Khmer Rouge, or the Killing Fields — how the Khmer Rouge had tortured, forced into labor camps, and murdered somewhere between 850,000 and three million fellow Cambodians in four years. The effects of the autogenocide were fresh. Everyone we met had relatives who’d been killed; no adult seemed to have a father. At the National Museum, I took pictures of two teenage monks, and when they saw me aim the lens at them, they came over to view their images in my digital camera’s display. We talked, using sign language, for what seemed like an hour. I watched the sun set over the Mekong River.

My Destination Asia guide in Cambodia changed my mind about organized tours, and I had changed my mind about being a tourist.

I did not want to go back to the ship.

The door shuts with a soft click behind you. Crack open another book.

•

Between ports, Kate and I developed a new, and secret, habit: We hid out in my cabin and watched episodes of Lost on DVD.

“I have so many papers to grade,” I’d say.

“I was going to read about Turkey,” she’d say.

Then we’d be leaning against pillows, with her computer in our laps, hunched towards the speakers, deliriously happy to be doing nothing.

“Should we watch another one?”

“I really think we should watch another one.”

It was rare that we had time for more than one episode. When we did, it was inevitable that Edwin, my cabin steward, would knock on my door during his afternoon rounds.

“Hi Edwin!” I would call. “We’re busy!”

But those doors were bomb-shelter thick. Without fail, Edwin swiped his card and opened my door, then looked at us apologetically, as if he had no idea we were in there. I’m pretty sure he always knew we were in there. But he had a job to do.

“Sorry, Edwin. Don’t worry about turning down the bed,” I’d say.

Edwin and I developed a new routine: turning down the bed was optional. All I wanted was ice in the ice bucket. The water from the tap tasted of salt and chemicals; the ice was made from filtered water, and I filled my Nalgene with ice every afternoon and waited for it to melt. Still, despite our agreement, Edwin managed to sneak in there most days and leave my bedcovers without a crinkle.

On the rare afternoon when I returned to my cabin to find the bed unmade, I felt disappointed.

But only a tiny bit.

Edwin always filled my ice bucket to the top.

•

Sometimes, in the classroom, the magical moment occurs without warning: The teacher-mask falls away like sloughed skin, the hierarchy vanishes, grades become irrelevant, and suddenly it’s just a bunch of people sitting in a room talking about things about which they are genuinely, personally passionate.

This happened the day we returned from Vietnam and Cambodia. The syllabus stated that we were to devote this class to the short stories of Tim O’Brien. But our minds were on the next thing, which was Burma.

“Do you guys even know anything about Burma?” I asked. Frankly, I didn’t know a whole lot about Burma. I’d done some reading, such as the history section of Lonely Planet: Myanmar, and Mark Jenkins’ “The Ghost Road,” — a harrowing essay about Jenkins’ attempt to dodge travel restrictions and traverse an old military road in northern Burma, which was off-limits to foreigners. The most horrifying scene Jenkins describes is when he is stopped, for the first time, by Burmese authorities on the forbidden road. He is taken into a room where an official interrogates him, but both of them know Jenkins can’t be hurt — he’s an American. Instead, the official brings in a Burmese boy, clearly enslaved by the military, and begins to beat the boy, as if to say to Jenkins, I can’t touch you, but now you have to live with the fact that your actions have led to this.

“Do you guys even know anything about Burma?” I asked. Frankly, I didn’t know a whole lot about Burma. I’d done some reading, such as the history section of Lonely Planet: Myanmar, and Mark Jenkins’ “The Ghost Road,” — a harrowing essay about Jenkins’ attempt to dodge travel restrictions and traverse an old military road in northern Burma, which was off-limits to foreigners. The most horrifying scene Jenkins describes is when he is stopped, for the first time, by Burmese authorities on the forbidden road. He is taken into a room where an official interrogates him, but both of them know Jenkins can’t be hurt — he’s an American. Instead, the official brings in a Burmese boy, clearly enslaved by the military, and begins to beat the boy, as if to say to Jenkins, I can’t touch you, but now you have to live with the fact that your actions have led to this.

I had a dream the night I read that essay. Semester at Sea was sponsoring a trip to see a Burmese man get beaten to death. I was supposed to lead the trip but I was late. When I arrived at the site, a naked man was tied down on a rack on the floor, and Burmese tour guides in military attire were throwing buckets of blood and feces on Semester at Sea students and teachers.

“This is to prepare you so you won’t get sick,” they said. Then they began breaking the man’s ribs, one by one, with a hammer.

This should have tipped me off that, subconsciously, I knew there was something questionable about the fact that we were going to Burma. In my dream, SAS had sponsored this beating-to-death — paid money to make it happen — because we were curious to see something “authentic.” The nature of the sponsorship rendered it instantly inauthentic. The drive to experience authentic “color” led to the dehumanization of a human being. It was the most dangerous form of exoticism.

Of course, it was only a dream.

“We don’t know anything about Myanmar or Burma,” several students said at once.

I told them about the military dictatorship that ruled by terror. Unlike the government in, say, Cuba, the junta did not even pretend to have any idealistic political goals to support their rule of oppression, other than the maintenance of their own power. Tourist sites, such as the Shwedagon Pagoda, had been restored by forced labor. The government shut the country off from the world. (They’d also “reclaimed” Myanmar — the country’s name before the British named it Burma—making the simplest discussion of the place controversial. Was calling it Burma supporting Imperialism? Was calling it Myanmar bowing to the junta?)

Many people consider it unethical to visit Burma at all, saying tourist money supports the junta. One is Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of Burma’s National League for Democracy. In 1991, Aung San Suu Kyi won the Nobel Peace Prize for her non-violent resistance against the military dictatorship. Now she lived under house arrest in Yangon.

Another such activist was Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who was slotted to sail with Semester at Sea for Spring 2007 voyage.

Gusty raised her hand. “I’m ROTC, and when I told my lieutenant I was going to Myammar, he was real upset,” she said. “He tried to get me to not go on Semester at Sea at all.”

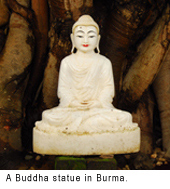

“Should we be going there?” I asked. Honestly, I wasn’t sure we should be going to Burma. Which is not to say that I didn’t really, really, really want to go to Burma. It was one of the most Buddhist countries in the world, and it had that untouched quality that reeled in the curious traveler. It was easier to meet people in a place that hadn’t been jaded by tourism. Burma had a forbidden element, like Cuba. The architecture was dreamy and drippy and glittering; everything in the pictures I’d seen seemed to be made of solid gold. It was unlike anywhere I’d ever been, which made it — just plain — exotic.

“Should we be going there?” I asked. Honestly, I wasn’t sure we should be going to Burma. Which is not to say that I didn’t really, really, really want to go to Burma. It was one of the most Buddhist countries in the world, and it had that untouched quality that reeled in the curious traveler. It was easier to meet people in a place that hadn’t been jaded by tourism. Burma had a forbidden element, like Cuba. The architecture was dreamy and drippy and glittering; everything in the pictures I’d seen seemed to be made of solid gold. It was unlike anywhere I’d ever been, which made it — just plain — exotic.

There were good arguments for traveling to Burma. An international presence reduced the number of human rights violations. Dollars weren’t that hard to get into the hands of people directly. It was all in figuring out how to do it —hiring a private truck to take you to Bago, for example, rather than taking a government bus. We could take what we’d learned and bring awareness of Burma to the States. The people, by and large, wanted us there, and we were exposing them to an alternative philosophy of life.

We spent most of the class discussing ways we could get our money to the people, rather than the government. The books would be on the ship when we got back. The world wasn’t waiting for us.

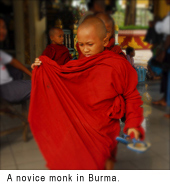

In Burma, I visited the Shwedagon Pagoda, the elaborate, gold-glittering Buddhist temple, in bare feet. I was approached by monks and I spoke with them about Buddhism. I stayed in a moldy hotel at the top of a mountain and observed a famous boulder — several stories high, dangling off a cliff — that was supposedly kept from rolling off because an embedded Buddha hair kept it balanced. I drank tea in tea stalls and swatted flies off Chinese pastries before I ate them. I asked cab drivers whether they preferred the name “Burma” or “Myanmar;” the consensus was “Burma,” which is the reason I have decided to call it Burma. I visited a rural home to watch a weaver make the traditional longi on a wooden loom and I purchased two of them, which are like wrap-around skirts. The money I spent on the longis went to the woman, not the junta. At the end, I hid out in a fancy hotel that Brian had booked without telling us it was fancy. And I liked it. The money we spent on the hotel went to the junta, not the people.

Out of the 35 students in Exoticism, only three felt we shouldn’t have gone. They came back wearing longis and woven shoulder bags. They came back with sides of a story.

“The world needs to know. People were so interested in talking to us I couldn’t believe it.”

“I’m totally starting a Myanmar awareness group when I get back to UCSD. I’ve already emailed all my listserves on campus.”

A few months after our voyage, towards the end of the Spring 2007 program, I received a group email from a fellow faculty member. Presumably because of Desmond Tutu’s influence, students on the spring voyage — who’d had no contact with Burma themselves — had organized and threatened to boycott the alumni drive if Semester at Sea continued to go to Burma.

The Institute for Shipboard Education cancelled Burma for all future voyages.

•

Then we were suddenly in India. I signed up for an organized overnight stay in a Dalit, or “Untouchables,” village. We spent the day at a nursing school for young Dalit women. We watched skits about a woman’s ability to support herself, even if her husband died in a horrible car accident, and about the importance of education. We played “catchball.” Or perhaps it was called “throwball.” We heard stories about the caste system and the poverty and discrimination the Dalit people faced in the workplace, and learned some alarming statistics about the rape of Dalit women.

Then we were suddenly in India. I signed up for an organized overnight stay in a Dalit, or “Untouchables,” village. We spent the day at a nursing school for young Dalit women. We watched skits about a woman’s ability to support herself, even if her husband died in a horrible car accident, and about the importance of education. We played “catchball.” Or perhaps it was called “throwball.” We heard stories about the caste system and the poverty and discrimination the Dalit people faced in the workplace, and learned some alarming statistics about the rape of Dalit women.

We slept on a roof in a Dalit village called Nalloor. Henry, our guide, joined us on the concrete roof where we would sleep, and instructed us to sit in a circle. He passed out little gold oil lamps that looked like cymbals and a woman walked the circle and filled each one with oil. Another woman came around and lit the floating wicks.

Henry spoke. “I am so grateful that Semester at Sea can spread the message of the injustice done to the Dalit people in India. You will take our message to so many people in your world. God bless you all. Let us take a moment to meditate on peace and freedom for all people.”

I peeked. Everyone had their eyes closed—the quick-witted librarian, the girl in my creative writing class who rarely spoke. I closed my eyes again, and meditated on peace and freedom.

When the moment was over, Henry asked if anyone would like to sing a song. Rhonda, an African-American from Alabama whose father was a minister, sang a song about Jesus. Then a student I didn’t know, a plain girl with wide-set eyes and a bowl cut, announced: “I’m thinking of a different song.” In a low voice, she began to sing “We Shall Overcome.”

Then we were all singing. And I had tears in my eyes.

There I was, free of cynicism, academic imperative, or judgment of any kind. I felt gratitude and hope. I felt good.

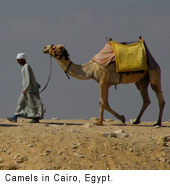

I signed up for a three-day tour to Cairo. Flaubert had written about his first sight of the Great Pyramids—it seemed like the floor of his soul had just dropped out. I watched the sun rise over the Pyramids. I knew how Flaubert felt.

Then I got back on the bus.

And so it went.

•

During my first few days on Outward Bound, years ago, I was that girl who suddenly “had to go to the bathroom” the minute it was time to scrape the pots. I let the boys carry my gear. Slowly, I started volunteering to carry the shovel or extra food. I offered to take gear for the boys. It took me months to feel tough.

On my second day in Bolivia, while searching out a cup of coffee, I got caught up in a demonstration against the privatization of water. Cholitas threw split-open fruits at me and stained my dress, then laughed hysterically at my stunned reaction. I had no idea what was going on. It took the rest of the week to figure out just how, exactly, I’d been supporting the opposition: by holding that coffee cup in my hand, in front of a shop that was supposed to be closed in protest.

On my second day in Bolivia, while searching out a cup of coffee, I got caught up in a demonstration against the privatization of water. Cholitas threw split-open fruits at me and stained my dress, then laughed hysterically at my stunned reaction. I had no idea what was going on. It took the rest of the week to figure out just how, exactly, I’d been supporting the opposition: by holding that coffee cup in my hand, in front of a shop that was supposed to be closed in protest.

On my third day in Burma, I took hundreds of photographs through a grimy bus window which came to be known (in my mind) as the “Burmese Dreams Series.” (“The blur’s on purpose! It’s to create a dreamy effect.”) I was using a different filter, one I’d previously considered a barrier: I’d used a window. I took my blurry experience of Burma home with me. I showed it on coffee shop walls.

On my second day in Cambodia, I saw skulls piled atop skulls; you could see where heads had been broken, and where bullets had entered. I bought a brief history guide to Cambodia and couldn’t put it down. This led to the reading of Khmer testimonials, which led to the watching of several movies, which led to more and more books, which led to obsessive Internet searches on ways to get paid to go to Cambodia as an English teacher. Who knows where that will lead.

Sometimes it takes months to trigger a change in the course of your life. Sometimes it takes one day. One comment by a Dominican-American writer whose work you admire.

Or one moment: The sight of the rack upon which Cambodian teachers were tortured.

•

You can get used to anything. Cambodians who starved in forced labor camps under the Khmer Rouge can tell you that. One woman I read about got used to eating grass, and looked forward to mice finding shelter in her make-shift home, so that she and her brother could hunt them and cook them. I got used to iceberg lettuce and looked forward to “taco day,” where once I’d gotten used to ice-cold showers and the sight of lice.

Everything is exotic to someone. It depends only on what you’re used to. When the shock of the unfamiliar eventually wears off, you’re left with a new “normal.” You’re a humanist. All it takes is willingness and time.

What if you’re long on willingness and short on time? The fascination fails to wear off. That fascination is bound to take real root somewhere and hold on.

When Semester at Sea nostalgia hits, it’s not about, say, India — though I feel another kind of yearning when I think of India. I wasn’t done with India. Someday, I would go back, and I’d begin somewhere other than the filthy chaos that was Chennai. And I’d gotten gypped in Hawaii with that “cultural” center. I’d have to go back. But these site-specific feelings were about the future, hope for what I would do rather than memories of what I had done.

When I feel nostalgia, it’s for my cabin.

At home, months later, I open the kitchen cupboard and I am hit by the strong smell of sweet Turkish coffee with its cardamom kick. This coffee, in its yellow paper sack with red Arabic writing running up the sides, is the smell of my cabin. One whiff and I’m back in my cabin, zipping up my black silk dress from Vietnam, getting ready for a social in the faculty/staff lounge, smearing sticky Egyptian sandalwood oil on the insides of my wrists with a plastic wand. There are ice cubes melting slowly in my ice bucket. My books, including newly-read guides on Burma and Cambodia, are upright and aligned, because Edwin has made them so. There is the reassuring sensation of the air conditioning. And the ceaseless rush of water past the porthole.

I forgot there were windows in Classroom 3. I got used to them.

I went back to Emerson College, where I’d taught the Exoticism course for five years. This year, it was a kinder, gentler Exoticism.

“Flaubert is such an ethnocentrist,” students would say. “He just lived in his own little bubble.”

I would tell them, “Maybe we should give Flaubert a break.” • 6 August 2007

All photos by author.