Hitler loved art. His taste tended toward classicism. The Greek ideal of beauty was his general standard in aesthetics. He once wrote the following memorandum about how he guaranteed that he would get “good” art for the Munich Museum. “I have inexorably adhered to the following principle,” Hitler wrote.

- “Degenerate Art:The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937. Through June 30. Neue Galerie, New York.

If some self-styled artist submits trash for the Munich exhibition, then he is a swindler, in which case he should be put in prison; or he is a madman, in which case he should be in an asylum; or he is a degenerate, in which case he must be sent to a concentration camp to be “reeducated” and taught the dignity of honest labor. In this way I have ensured that the Munich exhibition is avoided like the plague by the inefficient.

And it was. I suspect a number of contemporary curators and museum directors feel roughly the same way Hitler did about artists who “submit trash.” But what made Hitler, Hitler — and not just your average Museum Director — was that he was willing to go that extra mile. He did, actually, send artists to prison, the asylum, and the concentration camp.

The current show at the Neue Galerie in New York City (“Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937”) mostly displays art that appeared in the now-infamous “Degenerate Art” exhibits organized by the Nazis in Munich and then taken to other cities around Nazi Germany. The point of the “Degenerate Art” exhibits was to demonstrate just how bad modern art had become, according to the Nazi sensibility.

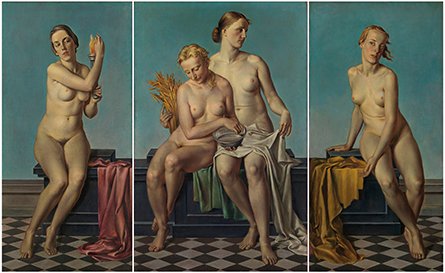

In the late 1930s, Hitler made it Goebbels’ responsibility to purge art of degeneracy. Goebbels appointed Adolf Ziegler, who happened to be one of Hitler’s favorite painters, to the position of Director of the Reich Chamber of Visual Art. Ziegler looked around and declared many of the artworks of his time, “the products of insanity, of impudence, of ineptitude, and of decadence.” Ziegler went about the process of seizing much of this “degenerate” art, some of which appeared in the “Degenerate Exhibit” before being sold off to other countries or destroyed. The show at the Neue Galerie includes paintings by Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Oskar Kokoschka, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Paul Klee — to name a few of the most well-known “degenerates.” The Neue Galerie’s show also displays some of the work that Hitler and the Nazi apparatus liked. There is a painting by Adolf Ziegler himself, entitled “The Four Elements: Fire, Earth, and Water, Air” (1937). This painting was a special favorite of Hitler. He kept it hanging in his Munich apartment.

“The Four Elements: Fire, Earth, and Water, Air,” Adolf Ziegler (1937)

Pinakothek der Moderne, Bayerische Staatsgemaeldesammlungen, Munich

Photo credit: bpk, Berlin/Art Resource, NY

There is a danger when viewing the Neue Galerie’s exhibit. The danger is that we enter the exhibit already “knowing” that all the art the Nazis thought was bad must be good, and that all the art they thought was good must be bad. There is some truth to this. But it is an easy truth. The question is whether we should ever approach the history of the Third Reich looking for easy truths. I propose that we should not. This has everything to do with the Holocaust. Nazism produced death camps, the likes of which had not been seen on this planet before. Nazis did not invent evil but their places of systematic human extermination were a new form of evil, one we are still trying to come to terms with. So, confronting Nazism, even in a seemingly less-vital area like aesthetics, requires a certain amount of care. You can’t come with pat answers. You have to let the disquiet emerge.

How do you let the disquiet emerge? You do it by trying to identify with Nazi sensibilities as best you are able. Here’s an example. The art critic for The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl, recently wrote a particularly courageous review of the Neue Galerie show. This is the crucial paragraph:

In the Ziegler, which Hitler owned, four nude Aryan beauties repose on a long plinth and wield attributes of fire, water, earth, and air. They are kitschy enough, as confections of a trumped-up sensibility that Hitler had wishfully termed “Greco-Nordic,” but well done, in simmering harmonies of light-blue sky and delicately shadowed, effulgent flesh. The pleasure imparted by “The Four Elements” is disturbing. In presenting the work, and other, lesser but not entirely miserable examples of “great German art,” Peters [the curator] plainly means to disrupt complacent assumptions about a moment when people, if untouched by the terror, might still have condoned some aspect of the Reich. Further complicating matters, not all the “degenerate” artists were first-rate, or even very good, as witness the cartoonishly grotesque sculpture of a head, by Otto Freundlich, that provided the chief image in publicity materials for the Munich show.

Schjeldahl does two important things with these comments. He admits that the painting by Adolf Ziegler (which Hitler loved) is a compelling painting. He also admits that some of the work that the Nazis hated wasn’t very good. This breaks down the boundaries between us (the right-thinking people), and them (the inscrutably evil Nazis). There is something inscrutable about the evil of Nazism. It is, and will always be, impossible to wrap one’s head around the knowledge that, on a daily basis in the early 1940s, trains of human beings were driven up to industrial crematoria, families unloaded, herded along into the gassing rooms, and murdered wholesale. That cannot ever “make sense.” But there is much of Nazism that can make sense. And to draw away from these aspects of Nazism, to protect ourselves from the elements of Nazism that we can understand, is to pretend that the evils of Nazism have nothing to do with us.

As Henry Grosshans wrote in his book, Hitler and the Artists:

[Hitler] was acquainted with the thought of Nietzsche, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Ranke, Treitschke, Bismarck, and Spengler. He read military histories, Ibsen’s dramas, the libretto’s of Wagner’s operas, and books on mythology. According to his fellow soldiers, Hitler read and reread Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Idea during World War I….

Hitler went out of his way to acquire famous paintings by Vermeer, Frans Hals, and Goya. As Grosshans wrote, “By 1945, over five thousand paintings by, among others, da Vinci, Jan Steen, Tintoretto, Rubens, Ingres, and Rembrandt had been secured, as well as tapestries, pieces of sculpture, and miscellaneous items.” Hitler’s collection was probably worth about four hundred million dollars. Grosshans quotes Janet Flanner from her book Men and Monuments in saying that Hitler’s art expenditures were probably, “the greatest individual outlay for beauty ever recorded.”

This is a disturbing thought.

The more one thinks about these things, the more it becomes clear Hitler was no more a philistine than any other political figure of the last hundred years, and probably much less so. His theories on art were brutal, his aesthetic decisions based on an idea of racial purity that trumped all other concerns. But the problem wasn’t that Hitler didn’t take art seriously enough — rather, he took it too seriously. He sent men to their deaths, on some occasions, around aesthetical concerns. Why was Hitler so bad, so evil? Well, that is the question so very difficult to answer. But distancing ourselves from Hitler, though an understandable impulse, does not make the question easier to address. It makes the question go away.

The terrifying but necessary thing to do, for those who can stomach it, is to look into Hitler’s thoughts on art and to realize that there are places where we agree with him.

Hitler’s abhorrence of Modernist art was a common reaction in his day. The paintings and sculptures of men like Kirchner, Dix, Barlach, and Beckmann were (and still are) disturbing. The work reflected a genuine crisis of the spirit. These artists rejected many of the values that had been seen, rightly, as constitutive of Western Civilization up until the beginning of the 20th century. It takes much training and even a certain amount of desensitizing to appreciate the work of the Expressionists, let alone see beauty in it. The beauty, when it comes, is a hard beauty. It is a beauty that comes of suffering and confusion and no little amount of despair. The artists Hitler tended to despise were the artists who, more often than not, chose to play with outright ugliness in their work. Even thoroughly non-Nazi art critics like Robert Hughes have wondered, often and with great pathos, why Western art so thoroughly abandoned beauty in the course of the 20th century. Lamenting the loss of beauty is not shallow and it does not lead to evil. The lament is not the problem. The problem, perhaps, comes from the idea that beauty can be an act of will.

One thing Hitler detested most in Modernist art was the depiction of a tortured and wounded Aryan soul. He wanted to see Aryans portrayed with healthy and robust souls, along with healthy and robust bodies. We can sympathize with this desire. But human beings, even the Aryan, are not like that. We aren’t healthy and robust. We are breakable and, more often than not, at least partially broken.

The life story of the artist Emil Nolde — whose work can be seen in the Neue Galerie show — is particularly instructive in this regard. Nolde was born in 1867 and later became an influential member of the group of Expressionists known as Die Brücke (The Bridge). He made images as challenging and innovative as anything produced in the early 20th century. He also made the fateful decision to join the Nazi party in the early 1920s. He was a nationalist and an anti-Semite.

“The Prophet,” Emil Nolde (1912)

But none of that was enough to save him from the Nazi art purges. Nolde’s art simply did not look right to Hitler and Goebbels and Ziegler. Looking at his famous woodcut, “The Prophet” (1912), one can see why. It is a stark woodcut, with thick and harsh lines. The prophet’s face droops downward, sallow and a step away from complete defeat. Nolde’s prophet does not bear a message of triumph. He has a sadder tale to tell. This isn’t to say that the prophet lacks strength. He has learned something, Nolde’s prophet. He knows that life is made richer by the trials of pain and suffering. Nolde’s prophet wants everyone to know that our greatest strength can be found, paradoxically, in our weakness. This was a spiritual insight utterly intolerable to Hitler. Hitler had emerged from his own pain and suffering with a different idea: Strength comes from strength, power from power.

Nolde was compelled to make art that expressed the power of weakness even while he professed Nazi doctrine that strength comes from strength. This proves how thin and sometimes imperceptible is the line between these two thoughts. The latter is so much more compelling. It is an idea we tell ourselves every day; that we must ever be strong. There is, then, a lesson in the otherwise lousy tale of “Degenerate Art.” We are all potential Nazis in our desire to master the turmoil in ourselves and in the world. And we can triumph over the Nazi temptation only when we surrender to the turmoil that can never be mastered. • 21 April 2014