Recently, while driving through the town where I live, I noticed a sign at a new restaurant. “EAT WELL BE TRUE,” the sign said. I was confused, at first. “Eat well be true?” What does that even mean?

Then I became angry. Why was some random restaurant in my own hometown telling me how to live? On the rare occasion that I do require input on how life should be lived, after all, it is to close friends that I turn, not restaurants — or department stores, or bikini wax clinics, or even the local Jiffy Lube.

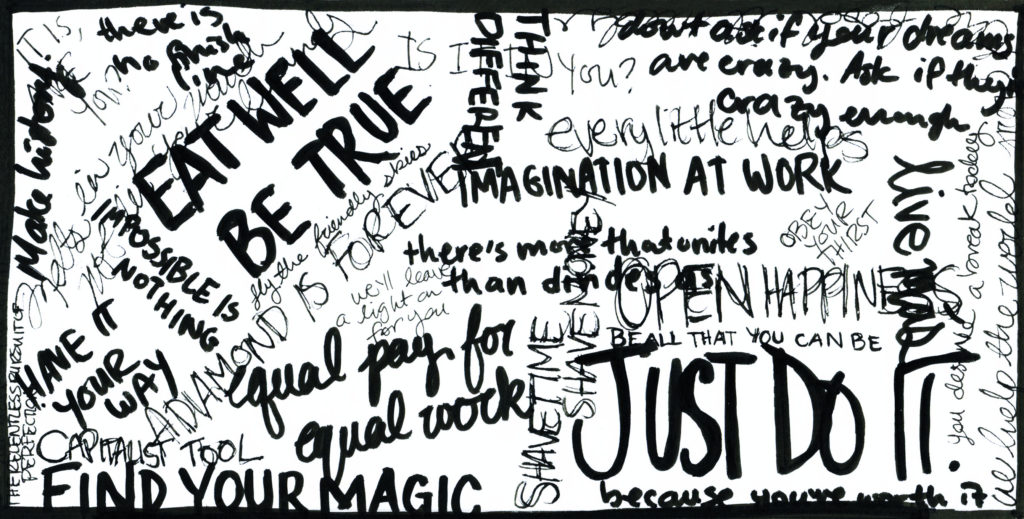

This wasn’t the first time I’d been on the receiving end of this sort of message, of course. According to industry pundits, “purpose branding” (as it’s called) is the future of marketing. I’ve even grown used to it, to a certain extent. When Taco Bell tells me to “Live Mas,” for instance, I don’t stop and ask what business a fast-food conglomerate has telling me how to live — let alone whether living mas truly is better than living menos, or mas o menos. Or what any of this has to do with tacos.

Sometimes I may even welcome the input. When a company that makes razors tells me that “It’s only by challenging ourselves to do more that we can get closer to our best,” for instance, I nod right along. Same when a deodorant company tells me to “Find your magic,” or a beverage company tells me to “Make history.” It’s the kind of thing I might even say to myself, over breakfast, perhaps, to psych myself up for the day.

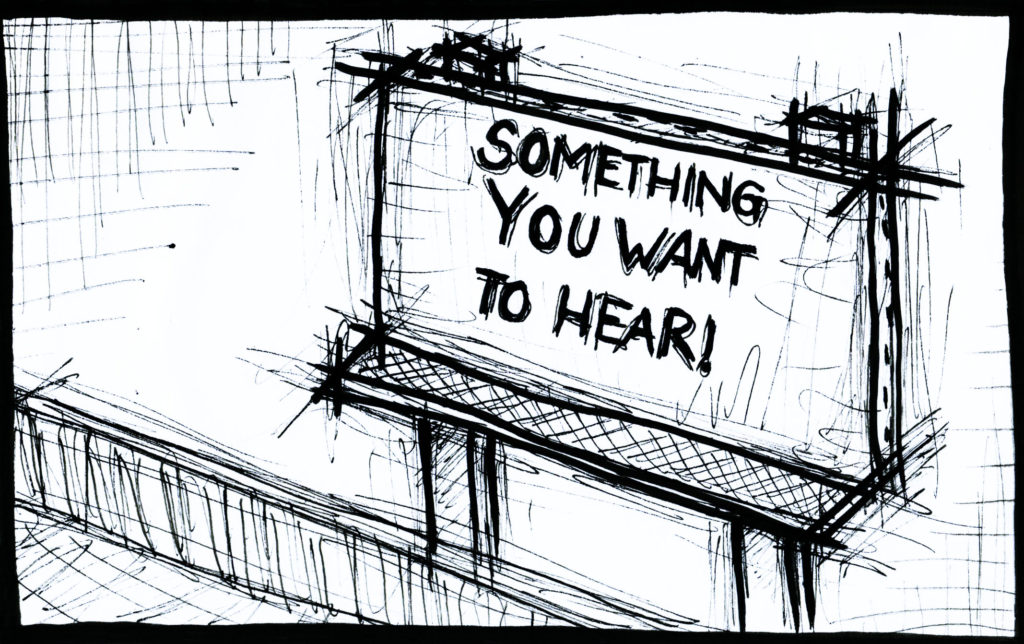

You might even argue that these ads are actually doing me a service, anticipating what I need to hear and then formulating it for my consumption. There is a certain sense in letting corporations do the work, after all. They’re the ones with all the resources. They’re the ones best positioned to scry our souls with market research, and then hire the hip advertising firms and production companies to deliver the needed encouragement. With the result that the final product (for by this point the ad is the product) is far more eloquent than anything I could have come up with.

Nike even won an Emmy for one of these ads, a moving montage of legless wrestlers, one-handed football players and hijab-wearing boxers accompanied by an introspective piano motif and the voice of Colin Kaepernick saying, “Don’t ask if your dreams are crazy. Ask if they’re crazy enough.”

The one I always liked best was the Under Armour ad with Gisele Bündchen. In it, Gisele, slick with sweat and panting with effort, tests herself against a heavy bag. The bag hangs in the middle of a bare and echoey industrial space. There is no music, no voiceover — only Gisele’s grunts and the rumble of a ventilation fan. Against this aural and visual void blink YouTubey comments from random internet users. “Stick to modeling sweetie.” “Gisele is soooo fake.” That sort of thing. And some positive comments, too. “Omg . . . I love her.”

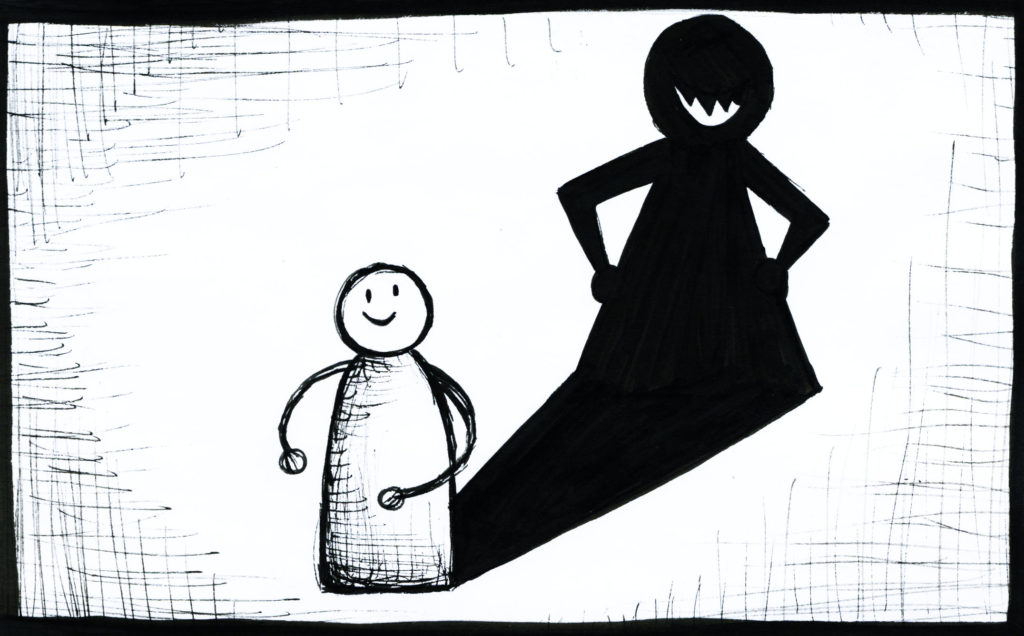

Gisele pays no mind to the superimposed text. She’s too absorbed in destroying the heavy bag. Which ultimately is the ad’s message, its little cube of life philosophy: Screw the haters — the admirers, too. Just do your thing, and do it with all your heart.

The “Omg . . . I love her” text could easily have been mine. Yes, I thought, when I first saw the ad. That.

But then the ad fades, the corporate logo appears — with the same suddenness as those random internet comments — and you’re left wondering whether it really makes sense to be getting your life philosophy from a company that makes underwear. Because while doing so does, granted, offer a certain shopper’s convenience, it also seems like the kind of thing that goes against some general rule of thumb, the kind of thing your grandmother might hammer into your head when you were young. And remember kiddo, never get your philosophy and your underwear from the same place!

The underwear peoples’ philosophy is always a bit simple, after all, and packaged with simplistic metaphors. (Life is not always like sports. In fact, life tends to be most interesting when it is not like sports).

More importantly, it’s generic. Which doesn’t much matter when it comes to underwear. Most people don’t require personalized underwear, or underwear that reflects their unique life experience, reading experience, cultural background, hereditary background, personal risk tolerance, etc. But this does not seem unreasonable to expect of a life philosophy — if only because otherwise we’d be dealing with 6,000,000,000 other chumps who were also just doing it, living like they mean it, eating well and being true, or whatever. And that would be irritating.

The thing is, it’s actually not always easy to reject these corporate come-ons. Especially when social justice issues are at stake. These are not just messages that we need to hear personally but messages that we wish others could hear. Like the burger restaurant ad declaring that no one deserves to be bullied. Or the ad for the multinational corporation specializing in personal hygiene products declaring that love doesn’t care who gives it. Or the ad for the outdoor clothing company declaring that politicians are self-serving and corporations are greedy. All of which is perfectly true, and not accepted as such nearly often enough.

It’s hard to reject the messenger without rejecting the message. And it’s hard to reject the message when it is not being voiced by anyone else — least of all the people elected to lead us. As those moral voices have withdrawn, replaced by ideologues, stooges and buffoons, corporations have moved in, to the point where morality itself has become a product, privatized like highways, data-mined from our Facebook accounts and sold back to us for the price of a shoe. It is, I submit, a sad state of affairs when we need to rely on a beer company to remind us that “there’s more that unites than divides us,” or a dating app to remind us that women must take the power, not wait around for someone to hand it to them. Not least because the corporations peddling these inspiring messages don’t believe them themselves. (“Equal pay for equal work,” said one ad for Audi, whose board of directors, at the time, was all men).

Anyway, corporations aren’t capable of belief. Belief is a human phenomenon, and companies are not human. They ape human mannerisms to score more sales.

And this is the really creepy part. For once the attractive mask is removed, be it Gisele or Serena Williams or Mila Kunis or whomever, what you’re dealing with is actually not a charismatic, butt-kicking human being but a venal corporation trying to slither its way into your personal headspace.

I’d lost sight of how unbelievably yucky this kind of thing is. It was only seeing it against the relatively bullcrap-free backdrop of my own home town that the yuckiness became once again screamingly obvious.

But why tolerate it anywhere? Why should my home town be more like the world at large and not the other way around?

In my pique, I was tempted to stop in at the new restaurant in my town and demand their views on what “being true” really meant. Who knows. Maybe they had actually given the matter some thought.

As it happened, the restaurant went out of business before I had a chance. The reason: “egregious” violations of state alcohol laws, failure to pay owed wages to contractors and employees, and a US District Court lawsuit alleging trademark infringement. Corporations like Nike, of course, aren’t likely to go out of business any time soon. Nor are they likely to be interested in a ruminative discussion of what “Just doing it” really means. No matter how I feel about purpose-driven branding, in other words, there’s not much I can do but ignore it.

The powerlessness can be frustrating. And suddenly I find myself identifying once again with Gisele — her fury, autonomy, and strength. Except, in the end, no logo. Because no logo is needed. •