Our habit of discussing political philosophies in terms of a spectrum from right to left ignores the actual variety of views lumped together under the labels “conservative” or “progressive.” So-called conservatives include free-market libertarians who want total separation of church and state, “theoconservatives” who insist that America is a Judeo-Christian nation that should be governed by Biblical laws and norms, and even a few white supremacists who despise libertarianism and Christianity alike.

Like “the right,” “the left” is a category so inclusive as to be meaningless. Some years ago the editor of a left-wing magazine asked me if I would consider writing a regular column. The editor told me, “We want to move in a more progressive direction.”

I replied, “Progressive, in the sense of Woodrow Wilson and Walter Lippmann and Herbert Croly?”

“No,” the editor answered, “we were thinking of Bukharin.”

Moderate American reformers, revolutionary Russian Marxist-Leninists — whatever. We’re all one big happy progressive family!

As my reference to Wilson, Lippmann and Croly may suggest, I have always identified with the Progressive-Liberal tradition in the U.S., and the trans-Atlantic left-liberal tradition of which it is a part. Left-liberalism is not just a watered-down version of some radical left. It differs fundamentally from Marxist socialism, essentialist identity politics, and other movements assigned to “the left.”

Left-liberalism, as the name suggests, is the left wing of liberalism, a philosophy with individual rights, civil liberties and democratic government at its center. We left-liberals have less in common with other “left” philosophies and movements than we do with “right-liberals” — the proper name for moderate conservatives in the U.S., UK, and similar societies with well-established liberal traditions. (Radical libertarians sometimes call themselves “classical liberals,” but they are not really part of the liberal tradition; their intellectual ancestors are nineteenth-century anarchists).

Here are a few of the institutions and ideas that unite left-liberals with right-liberals, while dividing left-liberalism from various other schools of thought to the left of center.

The Nation-State: The precursors of modern liberalism and republicanism evolved in premodern city-states. But in the modern world the inclusive, democratic nation-state is the unit of government in which liberalism has flourished best. With exceptions like Acton and Macaulay, from the days of Mazzini, Gladstone and Wilson to the present most liberals have considered dynastic or racial or national empires illegitimate and have favored self-government by nations. Left-liberals reject narrowly racial and religious definitions of national identity. But left-liberals tend to agree with J.S. Mill that a common language and a minimum sense of shared identity is necessary for a flourishing democracy.

If you find even liberal, democratic, tolerant nation-states inherently “problematic” or “exclusionary,” then you are not a left-liberal. The Cosmopolitan Justice booth is over there, next to the Identitarian booth.

Capitalism: The Marxist left hates capitalism. The lifestyle left hates consumerism. Left-liberalism is neither anti-capitalist nor appalled by consumer society.

We left-liberals are liberals — we place high value on individual rights and private property. Unlike right-liberals or conservatives, our sibling rivals, we worry as much about concentrated economic power as we do about concentrated political power. Left-liberals have no problem with public ownership of some things — public utilities, for example. But socialism is not an ideal for us, and we worry that even in “democratic socialism” the lines between economic and political power might be too blurred and easily abused. Left-liberals dread the two extremes of plutocracy, in which an economic elite monopolizes political power, and totalitarianism, in which a political elite controls the economy. From a left-liberal perspective, totalitarianism was the greatest danger in the 20th century and plutocracy is the greatest danger in the 21st.

Unlike old-fashioned right-liberals or “classical liberals,” left-liberals do not believe that deregulated markets can be counted upon to automatically eliminate dangerous concentrations of economic power in a modern industrial economy. What John Kenneth Galbraith called “countervailing power” — based on labor unions and small-business cooperatives as well as elected officials and government agencies — is needed to counterbalance concentrations of power in finance and industry.

Left-liberals dismiss the claim of right-liberals that political tyranny can be averted by the simple expedient of keeping government small and starved of taxes. The imperatives of national security and the need for industrial regulation and a social safety net make the small-government ideal of right-liberalism impossible in the modern world.

The best that can be hoped for in modern conditions is a “mixed economy” in the economic realm, in which economic power is divided among for-profit, nonprofit and public players, and checks and balances in the political realm, including the checks provided by an independent press and informed voters. This compromise is not as inspiring as the utopias of socialism and libertarianism, but it is responsible for more widely-shared freedom and prosperity than any other system in history.

Not what you’re looking for? The Revolutionary Spartacists are two booths down, under the big red banner.

Class: Left-liberals seek to ameliorate class systems, not eradicate them. This statement may be rejected by many of my fellow left-liberals. But a moment’s reflection proves I am right.

As a version of liberalism, left-liberalism prizes individual liberty and property rights. In an ideal world many left-liberals would prefer a classless society, a society in which the rich or educated or socially adroit do not pass on their advantages to their children. But our liberalism prevents left-liberals from proposing the sort of despotic policies that could erase class differences—say, confiscating all wealth and redistributing it equally per capita, or taking children away from their parents and raising them under different identities in state-run orphanages and boarding schools. At the same time, our liberalism forbids us to support the kind of totalitarian Maoist state that would be necessary to eradicate class differences (at least until class privilege reappeared among the “princeling” children of the communist power elite, as they did in the USSR, China and North Korea).

Without adopting illiberal methods and a totalitarian state, we left-liberals can still do a lot to reform the class systems in our various democratic nation-states. By socializing necessities like health care and education, or ensuring that they are provided cheaply by private producers, we can reduce the importance of class origins in daily life. And by breaking down systems of racial, class and gender discrimination, we can increase the upward mobility of the disadvantaged and the downward mobility of the privileged. But as long as parents can pass along some property and cultural advantages to their offspring, there will still be some kind of multi-generational class system.

So if you are on the left and your goal is to eliminate, not simply ameliorate, the class system, you are not a left-liberal. You might try the Khmer Rouge booth over there.

War: Unlike some schools on the left, we left-liberals believe that war can be legitimate. There would be no point in winning independence from an empire or dynasty for a nation-state, and then struggling to liberalize and democratize that nation-state, if we were unwilling to fight and kill to prevent foreigners from conquering the republic or traitors from dismembering it.

Because we left-liberals value individual rights, civil liberties and private property, we do not want a militarized, Spartan state. But we do not want a feeble, incompetent state either. We must have soldiers and police to defend the left-liberal democratic republican nation-state, along with the tax revenues and the government-supported military-industrial base to supply them.

Wars of conquest and enslavement and genocide are evil. But from the left-liberal perspective, there is a rebuttable presumption in favor of wars of national liberation or secession from colonial empires. Just as legitimate are defensive wars, by independent nation-states attacked unjustly by others, and defensive alliances to deter aggression and intimidation.

When it comes to the question of world order, left-liberals have generally rejected world federalism as both utopian and incompatible with national independence. At the same time, left-liberals have sought to replace international anarchy with some degree of international law. Among American presidents, the two Roosevelts and Wilson envisioned a “concert of power” among law-abiding great powers—a sort of global posse—as the least bad option.

If you are a pacifist who rejects war for any reason, or if you think democratic nation-states should be subordinate provinces of a world government, guess what? You’re not a left-liberal. Try the Quaker booth on the other side of the convention hall.

Now I know what some of you are thinking, as you are reading this — at least those of you who are Marxist radicals or cosmopolitan open-borders utilitarians or religious pacifists. You’re thinking: “He’s just a conservative in disguise!”

Certain factions on the right — racists, theocrats, radical libertarians — often have a similar response, on learning that a right-liberal or mainstream conservative acknowledges the need for anti-discrimination laws, or favors separation of church and state, or thinks that the modern welfare state should be reformed but not destroyed: “He (or she) is just a progressive in disguise!”

All of which simply underlines the fact that the arbitrary line between “left” and “right” is drawn smack through the middle of the liberal tradition.

Left-liberals and right-liberals are two sides of a single broad liberal school of public philosophy. The late Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., coined the term “the vital center” for this tradition. He was not talking about “centrism” as a partisan position within democratic societies. He was not naming the theoretical midpoint between the most conservative Democrat and the most liberal Republican. He was distinguishing the modern, democratic nation-state with civil liberties and a mixed economy from non-liberal models on the communist left and the fascist right.

Left-liberalism, then, is not the right wing of the left. It is the left wing of the vital center. In ordinary times when the stakes are small we left-liberals will debate our right-liberal siblings within the boundaries of a liberal consensus. But when the vital center is seriously threatened from without, by forces originating on the anti-liberal left or the anti-liberal right, left-liberals and right-liberals must close ranks to protect the liberal tradition we share.

If that’s not good enough for you, my leftist friend, you might try another booth. I hope you find what you’re looking for. •

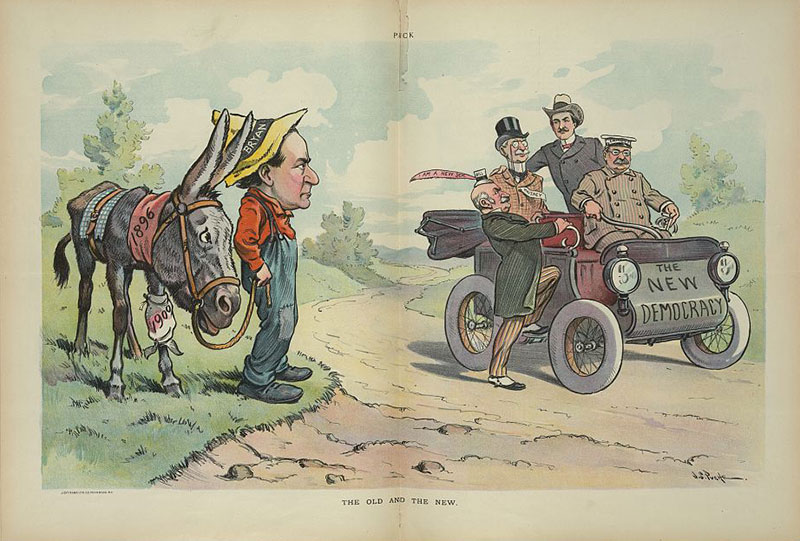

Illustrations courtesy of the Library of Congress (1 • 2 • 3)