(a special thank you to my friends for providing their quotes)

The giant mixed-media sketchbook sitting on my desk is nowhere near half full.

In May of 2020, when it was still taking up space in my childhood bedroom as my family waited for New Jersey stay-at-home orders to lift, I told myself I would finish a page every week. I started off fully confident in my ability to fill the 60-page sketchbook before the year was over; when this goal proved to be too ambitious, I resolved to fill it up halfway. More time passed and I kept bargaining with myself, each half-finished ink sketch or acrylic painting only extending my deadline. The months drifted on, I moved back to Philadelphia for school, and it became clear that artist’s block had rooted itself in my brain.

I wanted to make something of this challenge I’d set for myself. I knew I’d feel better after even a little progress, but among all my other priorities, pushing myself to sit down and create something only brought headaches, frustration, and an unrelenting sense of limitedness, both within the confines of my own mentality and those brought on by the pandemic. The whole situation left me considering the physical and mental limitations we’ve encountered over the past couple years — how they’ve shaped and altered our relationships with creativity in negative and, ultimately, positive ways.

I think creativity is so fluid that it can change instantaneously. I don’t think anyone’s perception of [it] ever remains the same for their entire life.

My own relationship developed early, long before the pandemic uprooted it. Growing up in a quiet suburb, my free time was dominated by random projects I created purely out of the need for something to do. Bored beyond belief without any siblings in the house to keep me company, I would take up residence on my bedroom floor with a collection of scissors, pens, paper, and colored pencils and, for lack of a better term, do my thing. Like anyone’s earliest drawings, mine consisted of colorful stick figures with impossible proportions; the projects became more complex as I navigated phases of wanting to become a fashion designer or theme park engineer, with cutouts of outfits or imaginary rides littering the floor from time to time.

Once I got a little older and my attention span became substantial enough to handle typing up a Word document, I would swap out pencils for words as my medium of choice. Nowadays, my mother will occasionally scroll through the notes app on her iPad and find some unfinished 2011-era short story or movie concept that she’ll quote relentlessly at me while I laugh and yell at her to stop.

(Don’t act like you don’t have at least one childhood project or memory that makes you want to scrub your brain every time your family brings it up. We all had the same phases.)

Dance, especially ballet, was another interest of mine that quickly became an artistic outlet. It took one show at age six to first draw me to the stage, a few more rehearsal seasons for me to develop a real passion, and several years of performances for my parents to accept that the “tutu phase” was evolving into more of a long-haul lifestyle.

Art, dance, and writing took a hold on my daily life as I began taking my passions seriously. My class breaks during the last couple years of high school were spent scratching dried paint out from under my fingernails and washing graphite residue off my hands, constantly in the process of some half-completed assignment for my afternoon art class that I’d unnecessarily put too much effort into for my own entertainment. Weeknights and weekends were dedicated to ballet practices and rehearsals for upcoming performances, two weeks of each summer reserved for international dance intensives. Emboldened by AP English classes, personal projects, and the allure of the media industry, I’d determined that I wanted to write for a living long before declaring a public relations major at Drexel University. These activities occupied my brain on the daily, but they also improved my mental health, providing relief from any stress or anxiety that I was (and am) dealing with.

Cut to two surreal years later, and my sketchbook keeps staring at me from across my desk like a skinny blue monster waiting to be fed something of substance. Last spring, one of the on-campus publications I was involved with became more of a commitment than I could handle, so I asked to take some time off and come back when I had less on my plate; a year later, despite how attractively they spice up my resume, I’m still lacking that motivation to start writing articles again. My first round of in-person auditions for the upcoming Drexel dance ensemble concert left me popping Aleve and wondering what made the process feel so unnatural — a year of learning and creating choreography from our respective apartments, or the hesitation to recommit to a large-scale performance.

Stress and the lack of real opportunity will make creativity seem more and more like a memory than something you engaged with regularly.

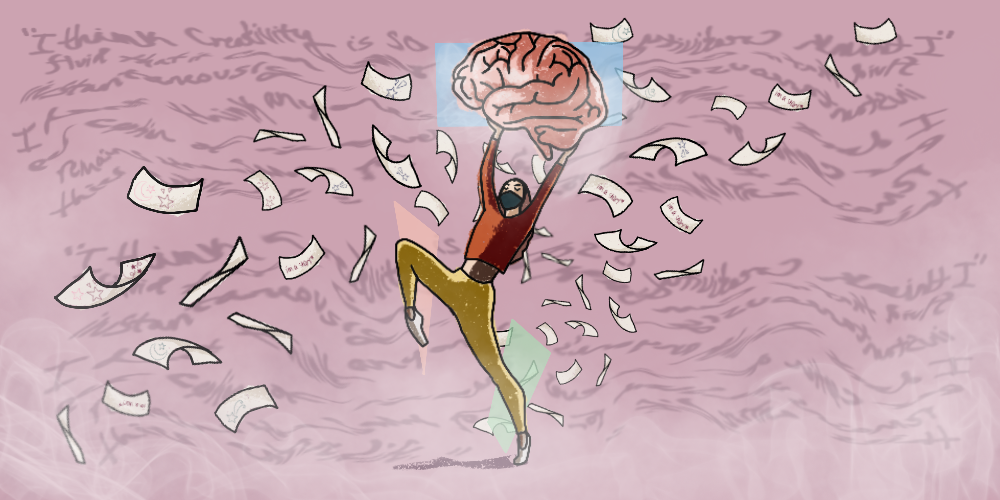

Artist’s block twists itself around your brain at the most inconvenient times. It seeps in and clouds your thought process just as you’re beginning to piece together an idea or build motivation. The kind I’ve experienced during Covid feels like being suspended in artistic limbo, a sticky buffer zone between wanting to express an idea you’ve been ruminating on for months, having the time and the space and the sources of inspiration — and still not being able to follow through. It’s seeing others’ post-quarantine projects (seemingly) flourish on social media and wondering whether you’re lacking the potential to display something of the same caliber, searching for whatever invisible factor is holding you back from letting inspiration set in, or pushing your boundaries, or even enjoying what you’re doing.

Neuroscientists have confirmed that isolation and uncertainty mess with cognitive function, so this isn’t a surprise, but that brain fog gets even thicker if you’re trying to make something from scratch. My friends have been feeling it, too — when I asked one how last year’s monotony affected their relationship with writing, they admitted that after promising themselves they’d finish writing a radio drama script in August, they still hadn’t touched it. The restrictions of the pandemic and online learning were a perfect breeding ground for writer’s block, which only worsens when you don’t get a change of scenery.

My relationship with writing [now] is sort of like those old noir films where a femme fatale enters some washed up dude in a trench coat’s office and says ‘I have a case for you.’ And while I say something along the lines of ‘oh no I’m retired lol,’ she drops a photograph on my desk of something I vaguely recognize and then I’m hooked. The ideas are there, but [eventually], like any good detective film back before people realized you shouldn’t take cocaine to cure illnesses, the case goes cold and I have to scramble to find the motive.

I recently experienced writer’s block during a previous internship, at a PR firm catering to Philadelphia’s dining industry, which I started in the fall of 2020.

Community was one factor that helped my coworkers and I power through that internship. Being able to (safely) work in person helped. We’d take the university shuttle into Rittenhouse every morning, sit around one table bouncing restaurant promotion ideas off each other, and refuel with lunches from local delis or sushi bars. Having that freedom to relax and socialize helped me feel less overwhelmed by the blog posts, news station pitches or press releases I’d be writing. The office’s sense of camaraderie brought us all together — but my writer’s block stuck around.

I recently realized I’d gotten too used to online school at the start of the pandemic. Eyes glued to a screen, with seven classes on my schedule and no discernible excuse to close my laptop, I used to stay up way past normal hours just to make a dent in the assignments I otherwise had no desire to complete, comforted a little by the knowledge that my parents were in their respective home offices doing the same. With too little space and too much on my to-do list, my mindset fed even more into the toxic productivity culture already present on so many college campuses. Now, I was back in an office and encouraged to write creatively — previously a source of stress relief — but that leftover “go go go” feeling would still make writing feel like a chore. When it struck in the long run, it also drained any energy I had to work on any other creative projects. Occasionally, I’d start something and then run out of steam — just as my friend wrote, the case went cold and I had to scramble to find the motive.

But of course in the world of Zoom and infinite cabin fever it becomes less and less of an opportunity to hear ideas and more of an endless void of nothingness. My best ideas come from when I’m sitting or standing in a crowd.

Putting occasional challenges aside, I did genuinely love my internship. Ironically, though, I spent the last week of it quarantined after a potential Covid exposure.

Cue eight days of takeout dinners on my bed, mornings spent on calls with coworkers I’d never see again, evenings spent on calls with friends I couldn’t wait to see again, and double-masked solo walks around campus twice a day. (That was the same week I submitted my last article for the school publication four days late and admitted to my editor that I needed a break.)

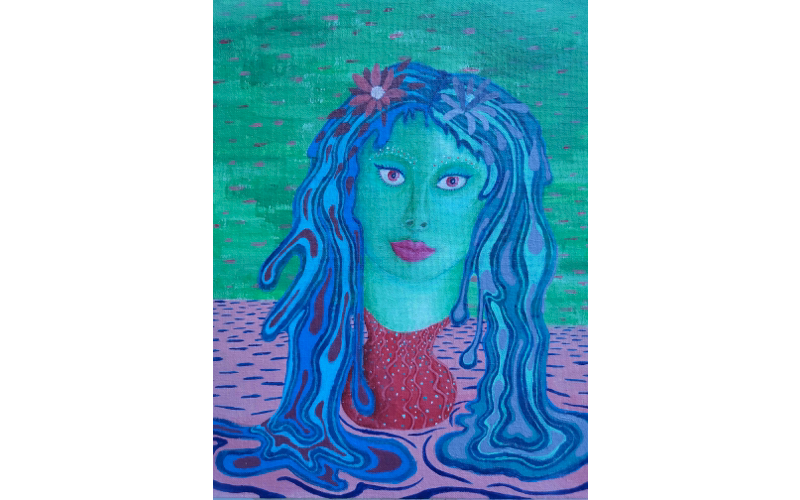

With my writer’s block thriving, I turned to visual art to pass the time. A few weeks before my exposure, I’d dug out a half-finished surrealist portrait I was planning to submit to Drexel’s literary magazine, a tradition I’d started my freshman year to motivate myself to keep making art. I was confident that finishing the painting during quarantine would pay off, but I also figured that the paint fumes and far-too-familiar cabin fever induced by previous lockdowns would get to me a little bit. Unsurprisingly, I ended up being right.

Having too much going on in life for personal projects is one challenge. But being physically confined to one place, with all the time in the world to immerse yourself in your own art and others’, and still not being able to enjoy yourself? That’s a whole new level of frustration, especially with a deadline on the horizon triggering stress hormones and impairing your creative reasoning.

I found myself struggling, spending hours hunched over my desk, missing my support systems, carving out details in alternating pink and green brush strokes to freshen up the previous layers of paint overlaying a year-old canvas. Every new day in isolation made it harder to push through that does this look good or is it too much ah shit I don’t know what I’m doing I just want to finish this already and it’s been three hours feeling that floated around daily, so I ended up looking through Instagram art profiles for inspiration. Whenever I’d finally put down my phone, my unfinished portrait stared back at me with red eyes, reminding me that I still had a way to go. It goes without saying that I went the whole week without touching my sketchbook.

But in between all the brain fog, more time to waste somehow became more time to think. There were still moments of clarity when I felt like playing around with the painting’s details or could at least visualize the finished product in my head, even though I had no access to the kind of community that helped me overcome creative blocks during my internship. While returning to city life just to go back into quarantine a few months later would rattle anyone’s mental health, the quiet hours of free time ended up keeping my mind afloat. I stopped dreading looking at the canvas and started seeing art as an enjoyable activity again — a feeling that stuck around after the finished portrait got accepted.

It’s definitely possible for hardship or restrictions to strengthen you or your art. If anything, it’s primarily about discovery and expanding your boundaries but it can be as simple as coming out empowered after doing something you aren’t normally comfortable with.

Internship and self-isolation behind me, I still wonder whether either experience had any positive effect on my creative process. I ended up talking to one of my close friends, an illustration major, who’d also been struggling to gain motivation. They’d spent their entire first year of art school at home, tackling assignments that required ten times the effort of my one-week quarantine project. Still, we both ended up producing work we could be proud of, directly influenced by our restrictions. At the risk of sounding like a motivational speaker, I’m starting to believe that we both gained a lot from change, even if it wasn’t always positive.

My last story comes from my dance experience. Last year, Drexel’s dance ensemble temporarily transitioned to an online format, another casualty for the performing arts industry during the Covid era. Our over-60-person company went from practicing in a spacious fourth-floor studio to logging into modified virtual classes, with even auditions conducted remotely. Coming home to a rearranged apartment, my roommates always had to navigate the maze of living room furniture stacked across the kitchen, area rug rolled up to clear the floor. No one was expected to stay on rhythm anymore. At that point, we were all too used to short-term blackouts, glitches, lags, freezes, roommates cooking dinner or pets making scenes in the background.

Being stuck in the same cycle of movement in the same space made me forget the importance of community and dance and how we inspire and feed off each other. I also felt that I was losing technique… a drive for dance… [and] energy, so it just started to feel like auto pilot as the pandemic progressed.

If you’ve ever taken any kind of dance class before, you know how environment is everything. You’re surrounded by people, grooving to music that’s filling the whole room, free to take up lots of space without concerns about coming into contact with walls, floor lamps, fake plants. No matter how draining your day was, you’re leaving it at the door and feeding off the energy of everyone you’re dancing with. It doesn’t — shouldn’t — feel like yet another Zoom-centered chore you need to check off your to-do list while spending your eighth hour at home and noticing how it’s suddenly gotten dark outside. Virtual rehearsals made everyone feel just as disconnected; our choreographers could only do so much to motivate us. We were all restless, impatient to get back to the studio and stage and enjoy ourselves again.

Then the shooting process started. Our winter performance was replaced by a dance film concert, with eight different pieces shot across separate locations over the course of two weekends. The film I was cast in was staged at Graffiti Pier, Philly’s resident abandoned-railroad-terminal-turned-unsanctioned-street-art-museum overlooking the Delaware River. The 15-minute film was shot in one single take throughout the 500-foot-long concrete structure, with recordings of our own voices playing in the background.

We’d never put all the groupings we learned over Zoom together in person. Still, there was something about filming in this huge outdoor space with an unlimited view of the Philadelphia skyline, walls exploding with color, wearing orange and yellow streetwear that I joked looked straight out of a cereal commercial, that made things click faster than expected. We shot take after take for hours on end, growing more accustomed to the 50-degree air and each other’s presences. The same collective frustration everyone felt while stuck rehearsing at home became a need to convey everything we’d been holding in to the camera; if we didn’t experience that frustration firsthand, there would be much less of a drive behind our performance.

The whole experience confirms my previous thought — that restrictions can fuel our ability to create just as they can impair it, molding our work into something more meaningful even if it came about in an unconventional way. (We’ve seen art influenced by the pandemic through virtual drag-opera collaborations, interactive theater, even just community art submissions.) Yes, we hit roadblocks and lose motivation and postpone things, but as long as we’re presented with challenges to our sense of normalcy, we have some potential to come up with even more innovative ways to work around them. In that sense, those challenges are even shattering our perceptions of how creativity itself functions.

Watching the final product onscreen, I can confidently say it looks stunning.

If something is limiting us from a normal experience, it can create a barricade or fuel for creativity; it just depends on the person.

I don’t mean to make this sound easy. No one I know, including myself, wakes up one morning and magically decides that their hardships are going to help them re-embrace their artistic pursuits. Regardless of the situation at hand, there are so many factors that affect our ability to create under pressure or restriction.

Education, socioeconomic status, and upbringing come to mind. I can acknowledge the advantages I possess as someone whose parents always encouraged their interests, whose university offered programs to cultivate them, who could afford adequate mental healthcare. Other people aren’t as privileged. Many encounter circumstances more traumatic than mine that stifle their creativity or put their lives on hold, leaving no room for projects they were previously passionate about. Even those able to go to college and turn their passion into a career path can get derailed by burnout; my friend admitted that going to art school made them realize they wanted to do “more than just art for the rest of my life”.

Mental health is one factor that stands out, especially in regards to the pandemic. Recent studies showed that the average amount of adults with symptoms indicative of an anxiety or depressive disorder increased by over 30% from the end of 2019 to the beginning of 2021; this comes as a surprise to no one. Speaking from experience, I think mental health can absolutely be linked to creativity; the same overthinking patterns that affect my brain because of my anxiety can fuel my attention to detail or ability to generate new ideas — on the other hand, they’ve also caused me to put too much thought into projects to the point of questioning whether they’re even worth completing.

Amid all this, I hold onto my belief that whatever circumstances we’ve inevitably struggled with, lately or long term, have just as much potential to enhance our creativity as they do to stifle it. No two writers’, dancers’, musicians’, designers’, artists’ blocks are going to be the same, just as it’s impossible to tell who’s going to be impacted more negatively or positively.

I guess I’m just trying to say that we’re all going through it in different ways, and at the end of the day, that’s okay.

It’s possible but it’s not always possible for everyone. Each person has a unique experience with their craft. For some it comes from joy, others from sadness. There is no determinable way to handle moments of limitation, but we also know for some it can be an opportunity worth taking.

The sketchbook’s gotten some action over the past few months. My schedule is way too hectic to keep up with it every day, but occasionally I end up with an idea, a handful of art supplies, and some free time on my hands. Even though I’m not submitting anything for publication any time soon, the few pages I’ve filled — a few stylized food sketches, tattoo designs, plants painted in impossible color combinations — were really fun to work on. (Sometimes I forget that this is supposed to be fun.)

My relationships with writing and dance have been growing stronger too; I wrote part of this essay from the parking lot of an abandoned North Philly warehouse where my company was shooting another dance film, and I’m back dancing in the studio again. Assistant editing an arts and culture publication through my current internship has exposed me to so many different types of writing that, in addition to approaching writing from a more editorial perspective, I’ve gained lots of inspiration for my own projects, career-related or not. Artist’s block still hits me over the head occasionally, but no matter how many times I’m low on motivation or focus, I know that my past experiences have shaped my creative processes for the better.

After dealing with all the past couple years’ chaos, I know the brain fog is guaranteed to fade out at some point. And even when it takes a while, it’s only a matter of time and resilience. •