Maybe one of the greatest gifts moving overseas has given me is

distance from the absolutely batshit health care debate going on in the

United States. Before I left, I could barely stomach the yelling, the

sign waving, and the pundits’ pronouncements that “the United States

has the best health care system in the world!” Ten minutes of the

nightly news was enough to bring me to the brink of a coronary

incident.

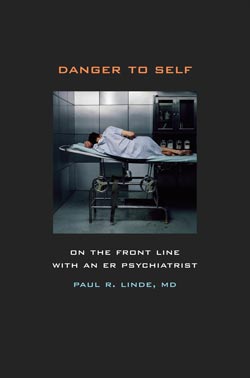

- Danger to Self: On the Front Line with an ER Psychiatrist by Paul Linde. 280 pages. University of California Press. $24.95.

- Doctoring the Mind: Is Our Current Treatment of Mental Illness Really Any Good? by Richard P. Bentall. 384 pages. NYU Press. $29.95.

- Healing the Broken Mind: Transforming America’s Failed Mental Health System by Timothy Kelly. 193 pages. NYU Press. $25.95.

- The Sixties by Jenny Diski. 160 pages. Picador. $14.

Like any other human being living below the standards of your typical cable news commentator, I’ve had maddening run-ins with the American health care system. In my poorest (and uninsured) days, I used a drug trial to gain access to antidepressants and regular contact with health care professionals. Getting health insurance didn’t actually improve matters all that much. Apparently going suddenly (if temporarily) deaf in both ears is not a legitimate reason to go to the emergency room, and my insurance company denied the claim. Everyone I know has a horror story, from a case of pneumonia while uninsured to being told their very real health condition was probably just a panic attack brought on by a husband’s going out of town for the weekend. Best system in the world, my eye.

Any reasonable person will tell you that the problem runs deeper than just a public insurance option. It is a system in desperate need of tort reform, a system beholden to the pharmaceutical industry and utterly lacking in preventive care and personal responsibility. But it’s hard to discuss subtleties when there are a hundred people on television screaming that socialized medicine will turn the United States into Nazi Germany.

Many areas in desperate need aren’t even being discussed, like America’s mental health system. In 2002, the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health released a report stating, “America’s mental health service delivery system is in shambles.” Timothy A. Kelly outlines the enormity of the problem in Healing the Broken Mind: Transforming America’s Failed Mental Health System as he witnessed it as the former Commissioner of Virginia’s Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation, and Substance Abuse Services, from doctors who overmedicate their patients and leave them in drugged stupors to community clinics left in budgetary limbo to insurance companies that will pay for those medications but not the rehabilitation that can allow the afflicted to rejoin society.

The overwhelming scale of the problem is one reason thrown around for the lack of improvement. The word “epidemic” is frequently used in relation to mental illness, and while the statistics vary from study to study, Kelly uses one of the more moderate figures: 26.2 percent of Americans will suffer from a mental illness at some point in their lives. Approximately 2.4 million Americans develop schizophrenia, while another approximately six million live with bipolar disorder. Ten years ago, a study found that even then $69 billion was being spent annually on mental health services, and yet recovery rates and patient satisfaction was disturbingly low.

All of that is daunting, but it wasn’t too long ago that the mental health care system was reformed — massively. In 1973, David Rosenhaun published a study in the journal Science called “On Being Sane in Insane Places,” and it was swiftly followed by public and professional outcry for reform. In the paper, Rosenhaun and some co-conspirators gave up personal hygeine for several days and presented themselves to mental institutions, their only reported symptom being a voice in their heads that repeated the word “thud.” After being admitted to the hospital, they went back to acting completely normal, but could not get any of the nurses or doctors to notice they were sane. Everything they did or said only reinforced the diagnoses they were given. The system in that era was full of invasive procedures, lifetimes lost being locked up on neglected wards. Jenny Diski was institutionalized a few times for her depression when she was younger, and she explains her experience in her new book The Sixties:

I was detained under a section of the Mental Health Act that deprived me of any right to agree or disagree with my own treatment and the right to leave. I was detained, literally, being held down by several nurses and injected with Largactyl, which put me into another narcosis, but this time with hideous nightmares I couldn’t wake up from… A woman next to me, incredibly in 1968, was put on the completely discredited insulin shock therapy, another given LSD “treatment.” Two or three of the patients had received lobotomies, and sat passively waiting to be discharged.

Rosenhaun’s paper was only one figure in a constellation of troubles in the industry. The antipsychiatry movement had Thomas Szasz and R. D. Laing questioning brilliantly and convincingly, even if deludedly, that mental illness might not even exist. Again, Jenny Diski:

The mad — the word became a banner of resistance — were outcasts, prophets, speakers of unspeakable truths, and were pronounced heroes. Pushed by malign normality, the mad, on behalf of those of us who hadn’t the courage, took a journey to the furtheset depths of the human psyche to look at what was really there, and who we really are.

The movement also corresponded with the development of some of the first effective pharmaceuticals for depression, mania, and psychosis. The result was widespread deinstitutionalization, the idea being that there was no need for the ill to languish in asylums. With proper medication, they could return to their homes, be supported by community clinics, and live normal lives. So how is that going, anyway?

Instead of being locked up in an asylum to be put in an insulin coma or having your teeth forcibly removed, patients are now locked into a diagnosis and corresponding pharmaceutical regimen. According to Richard P. Bentall’s Doctoring the Mind: Is Our Current Treatment of Mental Illness Really Any Good?, psychiatrist Loren Mosher — the former Chief of the Center for Studies of Schizophrenia at the National Institutes of Mental Health — resigned from the American Psychiatric Association stating, “The major reason for this action is my belief that I am actually resigning from the American Psychopharmacological Association.” And this was before the pharmaceutical industry tried to get the FDA to approve the use of antipsychotics for “juvenile schizophrenia.”

The new critics of the mental health system are not completely anti-medication. At no point did Bentall argue that we should go back to Laing’s approach of letting a psychotic smear her feces on the walls if that is how she wants to express her insanity. But the current system of find-the-correct-diagnosis-and-prescribe-the-corresponding-medication has led to a rigidity in the system and a belief that each mental illness is a solid, understandable thing. In fact, there is still debate about what schizophrenia is and how it relates to mania, which is why new diagnoses with the word “schizotypal” have shown up in the recent past. And while there are people who recover from what is originally diagnosed as schizophrenia, or at least conduct their lives despite the symptoms, the current idea of what this disorder is — chronic, debilitating, progressively worsening — allows the medical community to turn people who suffer from schizophrenia into schizophrenics. That is, not fully human. This was highlighted by a rather shocking anecdote from Paul R. Linde’s Danger to Self: On the Front Line with an ER Psychiatrist.

Suddenly, a rather large, unkempt man, a scowl on his face, stumbles out of one of the four seclusion rooms and ambles to the [nurses’] desk.

“What do you want, George?” asks Christina.

“I need to take a piss.”

“Get back in that room, or we’ll have to tie your ass up and give you a shot.”

After further verbally abusing the patient, working him up into yelling “fuck you” at the nurses, they do exactly that. They tie him down and give him a shot of medication, “delivered via an 18-gauge needle into the upper outer quadrant of his left buttock, where the thick muscle can soak up all those good tranquilizers.” You don’t have to be a follower of antipsychiatry to be grossed out by the exchange, or others of a similar nature that follow. When Laing created Kingsley Hall, where patients who suffered from schizophrenia or psychosis or mania were allowed to live unmedicated, the very mixed results closed the discussion on whether there were treatment options for serious mental illnesses. It’s unfortunate, because similar experiments — such as Mosher’s residential experiment called Soteria, which included medication but also life skill rehabilitation and other therapies — had very positive results. Other experiments during the 1960s and ’70s showed marked improvement simply from including, as Bentall put it, “warm and empathetic attention of another human being.”

While the various authors disagree on the way things must change — fewer drugs versus better drugs, refining and creating more specific diagnoses versus creating diagnosis spectrums, cognitive behavioral therapy versus psychotherapy — everyone agrees that the goal has to be re-humanizing the mentally ill. The days of the 10-minute pharmaceutical consultation has to come to an end, and it should be replaced with rehabilitation and empathy. Unfortunately for the state of the debate about health care reform, “We Want the Warm and Empathetic Attention of Another Human Being” does not make as good a chant as anything that includes the word “Nazi.” • 4 November 2009