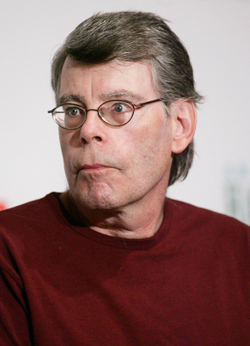

By now we are all familiar with the litany of reports about the god-awful state of reading in America, the table-talk obituaries about the marketplace for serious literary fiction, and the guttering candles critics keep lighting prematurely around the deathbed of the American short story. The litany goes like this: One of four Americans didn’t read a book last year; major book reviews are shrinking; magazines have dumped or drastically reduced their publication of short stories. If the literary market is lousy in general, short fiction is not even on the agenda. Agents willing to consider short fiction at all now “bundle” collections with novels or even nonfiction books. A sense of crisis is setting in: “What Ails the Short Story?” Stephen King asked after editing The Best American Short Stories 2007.

Contemporary masters still practice the form, including Alice Munro, Deborah Eisenberg, Lydia Davis, and Christine Schutt, to name only four personal favorites. And four of the five PEN/Faulkner nominees this year were short story writers — Amy Hempel, Edward P. Jones, Eisenberg, and Charles D’Ambrosio. (This year’s MacArthur Genuis Grant recipients included a short story writer as well, Stuart Dybek.) Although D’Ambrosio’s book had sold only 3,000 hardbacks prior to the PEN nomination, commerce isn’t the barometer of respect for the arts.

Still, the discontent amongst younger short story writers cannot be wished away by a few happy anecdotes. Short story writers now spend years crafting a collection only to be dismissed by agents or to throw their work on the mercy of university press book contests, a lottery for one-year creative writing positions. King blamed the state of things on “the bottom shelf”-ing of short fiction in the public eye, while the typical “death of reading in America” article pins shrinking audiences on competition from TV, movies, and the Internet.

And what about that wonderland of digital publication, which in many ways has been good for the national conversation about ideas? Online publishing still makes most fiction writers feel like second-class literary citizens. The short fiction contest at Zoetrope All-Story does not print its winners on physical pages but in a “special” online supplement. Some writers object on principle to the Zoetrope competition for this reason, while others shun online publications because they don’t count with academic search committees or the O. Henry Prize Anthology, which maintains a policy of having magazine editors submit physical copies of issues to its judges. (King said that he downloaded “a few” stories in reading for the 2007 Best American collection.)

The short story’s troubles stem from what Marxist critics used to call “the means of production,” which is to say that, unlike Chekhov or Fitzgerald, younger folks can’t feed themselves writing the stuff anymore. Thanks to MFAs and literary quarterlies, short fiction lives as a fine art, like jazz, classic music, opera, ballet, and poetry. King, who also blamed stories “written for editors and teachers rather than for readers” for the current malaise, got it wrong here: Thank heaven for the universities and nonprofits who see fit to support journals, small presses, and creative writing departments filled with brilliants who would be squeezed out by market forces. Yet these are reduced circumstances, making younger short story writers the literary equivalent of that generation of babies born today who will live shorter lives than their parents.

Many of the writers slated by King as “airless,” “self-referring,”

“show-offy,” “self-important,” and “guarded” probably developed their

first pimply love affair with reading through King’s technophobic tales

of possessed cars, malevolent consumer products, post-apocalyptic

wastelands, and Better Living Through Chemistry Gone Mad. When these

writers become teachers, I hope they recommend King’s inspiring book On Writing

to their students. But I don’t know why 2007’s Co-Arbiter of Taste in

Short Fiction feels the need to kick literary baby carriages down

critical subway steps — it has to be part of an ongoing grudge match

with the academy even if King doesn’t use the term “MFA.” King clearly

cares about fiction and went out of his way to read widely for his Best American

picks, but his argument is nonsense: the “airless” short story is by no

means the exclusive commodity of the present day, and there are too

many good short stories published every year to fit in the Best American volume, not too few, which is why the series always includes a supplemental list of 100 other highly recommended stories.

No pessimism of any sort can be admitted in the cheerful propaganda dispensed by the Glee Club of technology boosters who claim they’re going to save literature using Web sites, blogs, POD publishing, National Novel Writing Month, podcasts, iPhones, e-books, and the like. According to the gurus of the interweb, the cultural changeover from print to digital is supposed to usher in a golden tomorrow of universal democratic access. Sony, Amazon, and Google are the latest contenders in new e-book schemes that most people thought died a whimpering backroom death in the 1990s. HarperCollins is touting browsable free samples of books for the iPhone, starting with Ray Bradbury. Amazon is starting a fiction contest with Penguin, featuring online submissions to be judged by Amazon’s top citizen-soldier book reviewers. And from this day forward until the last instant of recorded time, every Harlequin Romance — hundreds of titles a year — will be downloadable from the privacy of one’s home.

The short fiction writer’s reaction to most of this stuff is probably “Ugh.” Students and business travelers, who can ditch armloads of books and read from a palm-sized device, will probably rejoice over the new e-books. These devices make the skin of most writers crawl. Many if not most serious fiction writers still think of digital media as a threat rather than an opportunity. The online world, especially for the older crowd, is still conventionally depicted as a kind of South Bank of London filled with the literary equivalent of bear-baiting.

The technology boosters think of themselves as saviors of a hopelessly backward humanity, while grim-jawed Luddites are bracing themselves for an apocalyptic cultural collapse involving “the death of literature” rather than simply the death of print’s dominance. Both camps in the Print Wars rely on a similar and false sense of crisis. Human beings crave and adore absorption in narrative. The delivery mechanism for thinking entertainment can be pressed into clay, carved in stone, repeated from memory around a fire, incised on scrolls, illuminated, printed, typed, Xeroxed, acted out, filmed, animated, YouTubed, Second Lived, IMed, blogged, or beamed from Earth to Mars and back again on handheld screens. The problem for short fiction is that novels grab what’s left over after the movies, cable, and online media.

But it’s not the technology that matters so much as the human need for a story and a storyteller, the proverbially needed figure the reporter in William Faulkner’s 1935 novel Pylon jokingly calls “a connotator of the world’s doings,” and even more ironically refers to as “the molder of the people’s thoughts.” Yet even after making these remarks, Faulkner’s reporter nevertheless struggles to write something that will be better than the news, surely the fiction writer’s main goal. In Pylon, Faulkner set out to document the lives of traveling stunt airplane pilots in order to figure out what was becoming of humanity in an era subjected to so much unprecedented speed, uprooted-ness, petroleum fumes, and outrageous technological change.

The “death of print,” the “death of literature,” the “death of books,” and the death of reading culture — the death of irony, and now the death of the short story — nothing dies more quickly than the “death of” article. In a 1996 Harper’s essay on the fate of serious literature, novelist Jonathan Franzen warned of dark ages ahead in the characteristic mode of the day:

if anybody who mattered in business or government believed there was a future in books, we would not have been witnessing such a frenzy…for an Infobahn whose proponents paid lip service to the devastation it would wreak on reading (“You have to get used to reading on a screen”) but could not conceal their indifference to the prospect.

Of course people did get used to reading on a screen. Some went on to fall in love, write blogs, form communities to discuss the works of Thomas Pynchon and William Gaddis, and do all manner of unpredictable, lovely, strange, obscene, and absurd things online that no one could have possibly foreseen. You have to hand it to humanity — really, there’s no stopping us from entertaining ourselves. But Franzen wrote because he wanted to know how books like Catch-22 had “seeped into the national imagination,” and whether fiction and fiction writers could still perform such miracle feats in his day. That question — similar to Faulkner’s reaction to a new world of flying machines in Pylon — is a durable good no matter what technological twists, turns, platforms, data storage methods, and operating systems we will successively pass and leave abandoned on Bill Gates’ The Road Ahead.

Another unabashedly Luddite text from the mid-1990s, Sven Birkerts’ book The Gutenberg Elegies, as its subtitle suggested, was mainly a funeral eulogy for The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. But it was clear-eyed one: “We are in the midst of an epoch-making transition. The societal shift from print-based to electronic communications is as consequential for culture as was the shift instigated by Gutenberg’s invention of movable type.” His main argument was that “the experience of depth” would diminish along with book culture, but, intriguingly, he also wondered whether “language is a hardier thing than I have allowed.” Birkerts thought it was possible that language might “flourish among the beep and click and the monitor as readily as it did on the printed page.” This wasn’t hot air: As Editor of AGNI, the literary magazine published by Boston University, Birkerts established a parallel web magazine that publishes literary fiction and poetry that may not ever appear in print.

•

The Internet has not devastated reading or abolished books. In some ways it has diminished reading and in other ways it has probably revived reading and writing more than TV or movies, especially for many young people, albeit in a more roving, browsing, grammatically questionable, and less attentive form, through email, chat, MySpace, and Facebook. The shift from print to the Web as the main entry point into the public square of ideas is a technological-cultural shift that gives anyone with a computer free access to the world of ideas. It is difficult to perceive the harm in this development. That said, despite the best efforts of Robert Coover (author of a classic “The End of Books” article) and Shelley Jackson (author of the CD-ROM-based story “Patchwork Girl”), as well as the digital experiments of the Brown University Creative Writing Program, it cannot be said that hypertext fiction has really taken off or taken root amongst readers or writers, either. That’s meant descriptively, not pejoratively. Jeff Parker and Kevin Kelly have written eloquently of the link as a “whole new literary joy” and a “type of intelligence common on the web, but previously foreign to the world of books,” respectively.

I loved Choose Your Own Adventure books as a kid. But fiction seems stubbornly resistant to the concept at present.

The salvation or damnation promised for the apocalypse just hasn’t happened; the apocalypse itself continues not to happen. We’ve stumbled on, not forward or backward so much as blindly and haltingly, into a “digital future” that never measures up to the best or worst predictions. The future tends to look eerily like the present because of the persistence of human nature. Books, those clunky old lovable things, don’t appear to be vanishing anytime soon. Even Shelley Jackson publishes them. And it happens to be the case that the online world craves a lot of text — in some ways it is a world of text or a world that cannot exist without writing.

•

Up till now, good fiction has been something consumed in solitude by people with free time and disposable income. At its best fiction becomes an all-absorbing world. There is a world of Pylon and of To the Lighthouse; Faulkner and Woolf may no longer be living people, but they have become places anyone can visit. As an art form with cultural value, serious fiction is also founded on a big risk that hardly ever gets acknowledged: You sacrifice a chunk of your precious and finite days on the premise that you’ll enjoy your time away and bring something back from your trip. This is reading, aptly described as a “shadow life” by Birkerts in The Gutenberg Elegies.

Great novels and short stories separate us from our fellow human beings, temporarily. They might leave us better equipped to imagine their suffering upon our return. But during the experience, we’re disengaged, sometimes mute. In that sense, serious fiction seems diametrically opposed to the kinds of imaginary communities, games, interactions, and buzzing, surfing, and chatting experiences available online. “Only connect,” E. M. Forster once wrote, but the how and why of connecting online seems categorically different from how fiction works. That quality of all-consuming solitary readerly absorption — what Birkerts champions as “depth” — is essentially humane and its evaporation is alarming. For many the plug-in required to run serious fiction gets disused or was never installed at the factory to begin with because the developers considered it a fancy and unnecessary optional extra. But the real question is whether the Internet and other new digital platforms are more of the same assault begun by movies, television, cable, and computer games, or whether, after serious fiction writing reaches its nadir, it can re-infiltrate the culture using a combination of books, the Web, and wireless screens. Call me, Ishmael — or, better yet, text me — when the answer emerges, because I don’t pretend to know.

Certainly an increasing amount of good short stories are available in online-only formats. University-backed quarterlies like AGNI and The Mississippi Review now have parallel Web editions featuring short stories, many by emerging and younger writers. Longer-standing online ventures include Blackbird, failbetter.com, storySouth, Drunken Boat, and The Barcelona Review. Newer online journals – Memorious, GutCult, Small Spiral Notebook — pop up on the NewPages site.

The short fiction available online can’t compete in quality with the better print quarterlies. The pay is virtual. The work hardly ever gets anthologized. But what’s done for love alone shows the resilience of the short story as a serious art form. Quantity is not quality, but the existence of so much fiction online, with so little pay for anyone involved suggests serious dedication and a level of unwarranted hope that is heartening. There are also a few professional advantages. It’s nice to have quality work online as a kind of Google-able C.V. Reputable agents browse these sites and contact writers directly if they like what they see. Online short fiction, then, is becoming a kind of “portfolio” format that many younger writers want when they are starting out.

Even so, fiction doesn’t work so well on the Web. Perhaps we’re not yet hardwired to sustain our concentration scrolling down a long Web page. There may be something biological about it, or least generational. It’s also likely that online fiction remains in a very primitive stage of its evolution. What we have now are stories originally designed for print that are slapped up on Web pages instead, regardless of length and with no consideration given to the very different form in which they will be consumed. There is a lot of fiction online, in other words, but not a great deal of online fiction. Nonfiction has found a plethora of ways to engage digitally: using links, shaping content to blog formats, getting shorter and snappier, and so forth. Short fiction hasn’t bothered much, and frankly online it doesn’t seem all that “short.” It’s not that online editors and browsing readers don’t like fiction. It’s more likely something at the core of fiction itself that resists quick scanning and browsing. And the paradox is that this quality is one of fiction’s greatest and most humane virtues.

•

Printed books are still how serious fiction writers make a living in our culture, either through publishers’ advances and movie deals, or by validating an author’s meal ticket at a university creative writing department. The existence of things like Oprah’s Book Club (in truth run largely through her show’s Web site) and Amazon.com suggests that printed books will endure in the digital age. As the literary blogger Scott Esposito notes in this thoughtful post, browsing the Web and browsing a good bookshop are far from mutually exclusive activities.

As far as I know, however, nobody in their senses would rather publish for free on MySpace if they can sell a book and get it printed. Would this change, however, if writers could get paid or become part of some excitement through these new technologies, in a somewhat similar fashion to a MySpace musician producing chart-topping songs? If there were an iTunes for new short stories that amalgamated writing from lots of journals, would that work for iPhones? The HarperCollins project to develop browse-able Bradbury for the iPhone appears to be a toe in this sort of water for the English-speaking world, although as yet the project is geared toward book purchases through free samples, not a fundamentally literary use of the technology.

One strategy that might work for the short fiction of the future — when printed books may be only one among many “platforms” available — is brevity. Both Esquire and Wired have created short story features based on very tight length requirements: Esquire.com’s Napkin Fiction Project hosted short stories that fit on a drinks napkin, while Wired limited its writers to just six words, as in Margaret Atwood’s piece — “Longed for him. Got him. Shit.”

Dave Eggers wrote microscopic fiction as a regular feature for The Guardian, and McSweeney’s recently published 145 Stories in a Small Box as well as an ongoing feature on its Web site in which writers completed short stories based upon F. Scott Fitzgerald’s notebook entries. When I see iPhones, my honest reaction is, can somebody please put little stories up on those tiny-tot screens? Miniaturization, beyond being trendy, seems to fit this browsing age. Stories that fit in a window on the Web or can be consumed on the train — little fiction jukeboxes — mimic the form of life people are actually living. The classic account of The Rise of the Novel by Ian Watt linked the appearance of the form in 18th century England to the reading habits of day. Rushed

readers might prefer to gulp down literature in pill form. Seriously: Should the fiction writer’s goal be to surf or resist cultural trends?

Writers mining old classics for novel forms could revisit figures like Felix Feneon, the turn-of-the-century French Anarchist journalist who created “Novels in Three Lines” out of strange incidents from news wire stories. The French word was “nouvelles,” which actually meant “The News in Three Lines” for Feneon, although the same French word means “short stories.” In a review of Luc Sante’s new translation of Feneon for The London Review of Books, Julian Barnes noted a tendency among writers of Feneon’s day that seems resonant: “The great descriptive and critical project that had been the realist novel – from Flaubert via Goncourt and Maupassant to Zola – had run its course, had sucked up that world and left little for the next generation of practitioners. The only way forward lay through compression, annotation, pointillism.” Gide complained that this type of writing was “not a river but a

distillery.” Surely food for thought here for short fiction writers trying to cope with the madness and delight of annotating the digital world.

The great American blog novel — yet to be written as far as I know — will not be a novel written on a blog but instead be the blog of a compelling fictional character, or a community of interacting invented literary personas, the online equivalent of the Portuguese Fernando Pessoa, who invented poets from various schools with clashing manifestoes. This approach would take fiction back to one its sources in the 17th century, the “jest biography,” such as The Life of Long Meg of Westminster. Somebody wonderful has already done this in comic form with the “blog” of the Incredible Hulk.

Another strategy that publishers could resurrect for digital media is Victorian-style serialization. Episodic structures with very brief chapters for browsing or downloading in bite sized chunks might work well online if they managed to retain the larger shape of a full-blown book. Charging for episodes or individual titles, as Stephen King once tried to do online with “The Plant,” is wrongheaded. An HBO style buffet, or annual subscriptions to an array of publishers, would work much better. In addition, publishers probably ought to consider reviving another old idea — producing preview anthologies with excerpts from their upcoming books as if they were magazines, not just single-publisher PR newsletters like The Borzoi Reader. Made available for free online, these would act like the old Works in Progress and New World Writing to generate pre-publication buzz. The motto of the latter, “Today’s New World Writing Is Tomorrow’s Good Reading for the Millions,” now seems almost unbearably touching, especially when one learns that the 1952 issue peddled works by William Gaddis and Flannery O’Connor: paperback price, fifty cents.

•

Thomas Pynchon once asked, “Is it OK to be a Luddite?” And Stephen King wrote in Time that “you can have my gun, but you can take my book when you pry my cold, dead fingers off the binding.” Birkerts described the advent of digital culture as entailing a death struggle between “technology and soul.” Okay, we get it, elders and betters, yes, duly noted, caveat lector. But many younger writers just feel differently about all this stuff. We no longer view our computers with universal suspicion, as HAL 9000s in waiting that will turn on us one day or another. Many of us type instead of writing and browse as much as we read, especially for ephemera like news and commentary. Unlike our parents or older brothers and sisters, we were raised up on Atari and IntelliVision, we learned BASIC at school and played Frogger down at the arcade. We’re actually fond of this junk. Those of us born in the 1970s are a straddling generation who knew life Before and After the digitization of everything. We’re straddlers of centuries and millennia as well, of the end of the Cold War and the beginning of the post-September 11 era.

The main thing is that serious fiction writing — that collective enterprise one might call RIPPING YARNS, INC., whatever the delivery method — cannot be allowed to go away. Writing has survived and adapted to film and television and it must survive and adapt to digital media, too. The problem with both the Luddites and the Technorati is that they tend to moralize technology itself, as if a screen or an iPhone or a web page or a blog could be “good” or “bad” by definition, rather than simply representing a number of blank, inert platforms for the same basic human storytelling impulse. It’s the stuff on these pages and screens that matters. Whether it becomes valuable to culture depends on qualities that probably don’t change all that much. Not only are the Luddites fighting a losing battle — although it’s always an attractive temptation to present oneself as a heroic representative of a lost era in a world newly diminished by barbaric sound and fury — but they are also missing out on a specific historical opportunity to cross the Thames and try to establish a Globe or two on the South Bank of the digital divide. • 12 October 2007