Being cool is mostly about posture. It is a way of holding your body. It is a certain expression on your face. It’s the way you handle a cigarette, but not the way you smoke it. Maybe you never even take a puff; you just let the thing dangle in your right hand, smoldering, until it burns out.

- “American Cool.” Through September 7. National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C.

There is a photograph of Lauren Bacall in the current exhibit (“American Cool”, through September 7) at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. The exhibit consists almost entirely of photographs, many of them now iconic. These photos trace the history of cool people in America from Frederick Douglass to Benicio Del Toro.

In the photograph of Bacall, she is standing against a wall. Her right leg is cocked to the side and she’s got one hand stuffed in her pocket. Her face is half in shadow and she isn’t looking toward the camera. She’s holding a cigarette in the first two fingers of her left hand. Elegant, nonchalant.

Bacall looks hard in the picture, but not too hard. She isn’t angry, but she might deliver a cutting comment at any moment. Or she might ignore you altogether, if you had the nerve to walk up to her. Her posture against the wall is easy. To be cool, there must be ease. The posture of cool is relaxed, never rigid. A soldier stands to attention and holds his or her body erect. A person being cool never does that. A cool person slouches or bends. A cool person leans against a wall or sinks down a little in a chair. A cool person lets the eyes lid over, too, or squints. And yet, the cool person must also be aware and alert, ready to say something cool, or to dismiss the person saying or doing something uncool. The cool person must be limp, but ready.

It is said that the jazz saxophonist Lester Young (1909-59) was the first person to use the word “cool” to mean something other than temperature. Over time, the concept of cool became desirable and distinctly American. Being cool became an unambiguously good thing. As the introduction to “American Cool” puts it, “To be cool means to exude the aura of something new and uncontainable. … Someone cool has a charismatic edge and a dark side. Cool is an earned form of individuality.”

But the goodness of cool was not obvious to Lester Young. He was cool more or less by necessity. As the exhibit puts it, “When Young said, ‘I’m cool’, he meant, first, that he was relaxed in the environment and, second, that he was keeping it together under social and economic pressure as well as the absurdity of life in a racist society.” The fact that Lester Young was trying to “keep it together” under social pressures and amidst the absurdity of racism suggests that the posture of cool is often just that, a posture. Cool people want to look relaxed for the very reason that they are not, actually, relaxed. Lester Young was famous for being an extremely sensitive and touchy person. Billie Holiday once said of Lester Young that, “you can hurt his feelings in two seconds.”

Somewhere at the root of coolness, then, is sensitivity, trauma, fear. Lester Young medicated himself with drugs and alcohol. He could barely blow his sax at the end of his life because he was so sick from liver disease and malnutrition. It was, to say the least, an intense struggle for Lester Young to “keep it together.” He wore dark glasses in smoky clubs long after midnight and slouched against the wall glaring at the audience. But this was no triumph. Lester Young died of being cool.

You could say the same thing of many Americans featured in the “American Cool” exhibit. You could say that James Dean died of being cool, as did Marilyn Monroe. Lester Young’s friend Billie Holiday was cool. She drank and drugged herself to death too, unable to cope with the same social and racial tensions that were driving Lester into the ground. Jack Kerouac is also featured in the exhibit. A white man, he didn’t face the specific horrors of racism as Holiday and Young did. But living life was hard for Kerouac, too. Here’s a passage from On The Road: “I realized these were all the snapshots which our children would look at someday with wonder, thinking their parents had lived smooth, well-ordered lives and got up in the morning to walk proudly on the sidewalks of life, never dreaming the raggedy madness and riot of our actual lives, our actual night, the hell of it, the senseless emptiness.” He played the cool guy to the end, dying of cirrhosis of the liver at age forty-seven.

Not everyone in the exhibit is an alcoholic or a suicide. There are those who picked up on the style and posture of cool without feeling the attendant fear and panic. But there are enough train wrecks of human beings in the exhibit, there are enough Lester Youngs, to drive the point home. Being cool is not so much an achievement of confident individuality as a desperate holding on and holding out against the terrors of existence. Cool people stand there looking blasé and nonchalant because they are anything but.

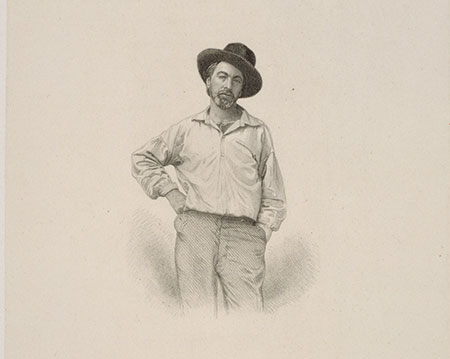

Americans started learning how to be cool sometime in the middle of the 19th century. The first cool American was, perhaps, Walt Whitman. In the “American Cool” exhibit, there is an early edition of Leaves of Grass. Whitman published his original edition of the work on the Fourth of July, 1855. On the title page of that first edition, which included the name neither of the author nor the publisher, was a portrait, an engraved daguerreotype, of Walt Whitman himself.

Walt Whitman, Samuel Hollyer (1854-1855)

Damn if Walt Whitman doesn’t look as cool as any 1950s jazz man in that daguerreotype. He’s got his left hand stuffed in his pocket and his right hand cocked on his hip. His head is tilted to the side and he’s wearing a black hat with what the engraver called “a rakish kind of slant.” No cigarette, but Whitman’s posture and demeanor is pretty similar to Lauren Bacall‘s.

Malcolm Cowley wrote about the engraving in his 1959 introduction to a reprint of the original edition of Leaves of Grass: “It is the portrait of a devil-may-care American workingman, one who might be taken as a somewhat idealized figure in almost any crowd.” According to Cowley — and to plenty of other people who’ve taken Whitman at his word — Leaves of Grass truly is a “song of the self.” “Not only,” Cowley wrote, “did Whitman choose his idealized or dramatized self as subject of the book; not only did he create the new style in which it was written (working hard and intelligently to perfect the style over a period of six or seven years), but he also created the new personality of the proletarian bard who was supposed to have done the writing.”

But if “cool” is really just a posture of ease and of “keeping it together” in the face of trauma and fear, then Walt Whitman’s coolness should be no different than that of Lester Young. Whitman’s cool should betray signs that it is the pose of a scared kid waiting for the other shoe to drop.

“I celebrate myself,” Whitman declares in the very first words of his poem. A few lines later he tells us more about this celebration. “I loafe,” Whitman writes, “and invite my soul, / I lean and loafe at my ease.” All this leaning and loafing and self-celebrating. It is practically a manifesto on the attitude of “cool.” It is like a how-to guide that Lester Young could have used in teaching people how to slouch through the jazz clubs of New York City.

Yet, it seems that Whitman had his doubts. As he got older and continued to revise the poem, Whitman had a way of softening the edges of his confident coolness. Here’s what Cowley has to say about those revisions: “‘Do I contradict myself?’ Once Whitman had asked the question defiantly, but now it worried him.” Whitman even changed the opening to the poem. In 1881, he expanded the line to “I celebrate myself and sing myself.” It is as if Whitman was admitting, with the inclusion of those extra words “I sing myself”, that the confident devil-may-care attitude of Leaves of Grass had been something of an act. The bluster and immediacy of his first proclamation of coolness gave way to something more distanced and reflective. In short, he couldn’t keep the cool going forever. The pressure of being cool was too much, even for Walt Whitman.

The burden of cool passed from Whitman on to other Americans. In the early days of cool, the era before 1940 that the National Portrait Gallery exhibit labels “The Roots of Cool,” the figures of cool tended to have a lower profile and a greater degree of social marginalization. Heroes of the era of the Roots of Cool include figures like Frederick Douglass, the boxer Jack Johnson, and Bessie Smith.

Then, in 1940, America experienced what the exhibit calls “The Birth of Cool.” This is the period of Lester Young and Lauren Bacall, of Humphrey Bogart, Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra and James Dean. This is the period of jazz and Beat culture and film noir. This is the period where people start to call themselves cool, to self-consciously assert the desire to be cool.

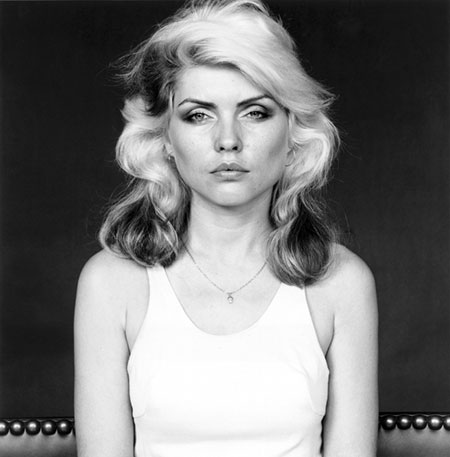

“The Birth of Cool” led to “Cool and The Counterculture, 1960-79.” The cool saints of this era are Muddy Waters, Steve McQueen, Jimi Hendrix, Joan Didion, and Deborah Harry. These people were so cool they didn’t even bother to say it. They let other people do that. Counterculture cool ended around 1980 when, “the selling of rebellion as style became ingrained in cool.” This part of the exhibit includes Madonna, David Byrne, Kurt Cobain and Tony Hawk as examples of the last period of cool, the period that leads all the way to the present.

Deborah Harry, Robert Mapplethorpe (1978)

It is interesting to consider whether we’ve experienced the final phase of cool. Have we witnessed the birth, ascendance, and then petering out of cool? Is it possible to be cool anymore, cool in the way that Lester Young or Lauren Bacall could be cool? If it is not possible to be cool anymore, does this mean that the specific suffering experienced by people like Lester Young no longer exists? Were the social tensions and anxieties of the late 19th and 20th century so central to the emergence of the phenomenon of “coolness” that it cannot exist without them?

You don’t see the postures of cool as much today as even a couple of decades ago. You rarely see public figures smoking in public, and almost never with that I-don’t-give-a-damn stance of Bogey or Bacall. Nobody slouches in the 21st century like the slouchers of the 20th.

The death of cool is, in the end, an ambivalent sign. It could be the result of a greater general social health, a purging of the fear that led to coolness in the first place. But it could just as easily be a transformation of fear. The death of cool could be the sign that we have learned new ways to hide our anxieties, ways that are not yet apparent, not yet obvious and nameable. We’ll need a Lester Young of the 21st century to invent a new word for whatever it is we do to hide our fears today. In 2014, we haven’t yet met that person. We’re still lingering on the vapors of the last few cigarettes smoked by the aging cool cats of the previous century. • 14 July 2014