On a spring day in 1913 students at the Art Institute of Chicago held a mock trial for the aesthetic crimes of the artist Henri Matisse. The event was a response to the Art Institute’s exhibition of works from the large Armory Show held earlier that year in New York, which was the first encounter many Americans had with European modernism.

- “Matisse: In Search of True Painting” Through March 17, 2013. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The trial was a well-staged performance for a crowd of students and patrons held on the south portico of the Institute, its archways providing a proscenium for the theatrics. Guards brought in the satirically named artist “Henry Hair Mattress,” his hands manacled as he was pushed in front of the court at the “point of a rusty bayonet,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune. The prosecution presented the evidence of three canvases — said to be that of the artist but, in fact, rough copies of three Matisse works from the show: “The Blue Nude” (1907), “Le Luxe I” (1907) and “Goldfish” (1912). The crimes were read to the jury and included “artistic murder, pictorial arson, artistic rapine, total degeneracy of color, criminal misuse of line, general esthetic aberration, and contumacious abuse of title.” (In case you were wondering, contumacious is a “stubborn or willful disobedience to authority” though this “crime” seems the lesser one of the list.)

“Goldfish” (1912)

The copies of Matisse’s paintings were so unsettling to the all female jury (an irony in 1913 before women had the right to vote) they caused a collective fainting. The verdict was unanimous. The canvases were burned to the excitement of the crowd, and then, in a moment of pure Greek tragedy, the executioner stepped forward and the “shivering futurist, overcome by his own conscience, fell dead.” His body was carried to the other side of the Art Institute with onlookers in procession, ending in a humorous funeral where a student read a eulogy, concluding: “You were a living example of death in life; you were ignorant and corrupt, an insect that annoyed us, and it is best for you and best for us that you have died.” With this, they planned on burning Matisse in effigy but the police stepped in before the image of the French modernist could be set ablaze. Even for this performance, burning the artist went a bit too far.

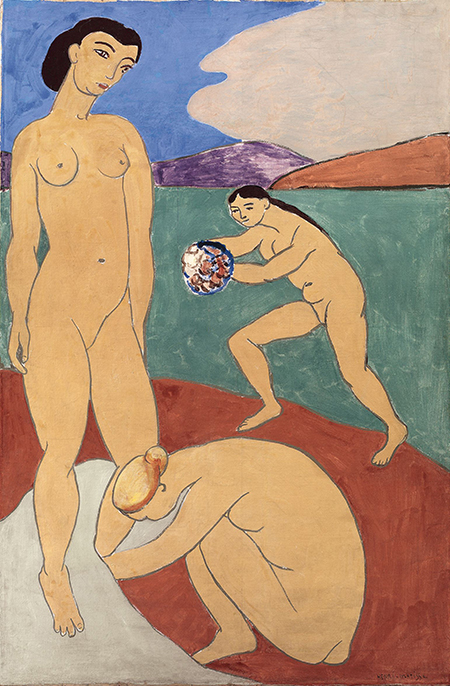

“Le Luxe I” (1907)

This revolt against modernism was an acutely violent one, more so than the acerbic words of critics and artists that were hurled at the Armory Show and those cubists and Post-Impressionist works on display. If modern art was about “artistic murder” as those Art Institute students so claimed, then their mock trial was its own form of modern performance art with its bonfire jubilation of Matisse’s copied canvases. Burning art or books (or even witches) holds this paradox for it is often not about the thing being burned as much as it is about maintaining an idea. Preservation often depends so much on destruction. In this sense the mock trial was more than outrage, but rather a claim to an artistic process anchored to the rigors of academic painting. What hovered behind the outrage, what angered the critics and the students, was how Matisse used the canvas. As much as this trial was about modernist aesthetics it was also about a question that has lurked at the edges of modern art for decades: What makes a canvas a painting?

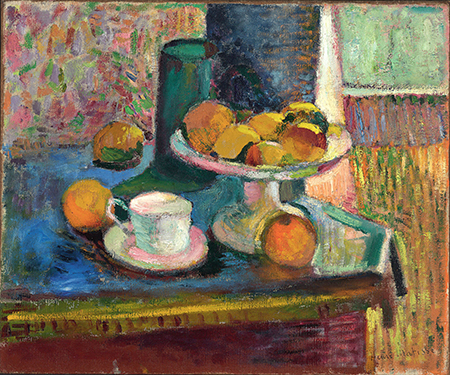

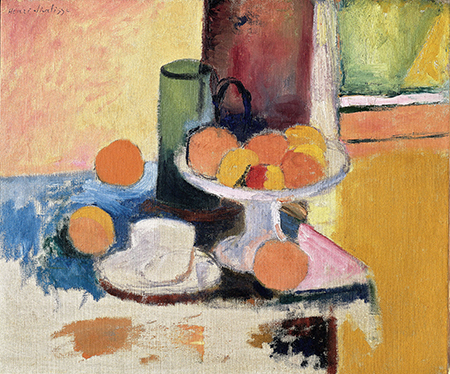

“Still Life with Compote, Apples, and Oranges” (1899)

“Matisse: The Search for Pure Painting” explores this question in a slightly different way. Exhibiting 49 paintings of the hundreds of works Matisse completed during his life, the show illuminates the importance of experimentation and the painterly process in understanding his works. In displaying canvases created in pairs or a series, the show makes this process, these experiments with paint on canvas, the creative energy of his art.

“Still Life with Compote and Fruit” (1899)

From the first spacious gallery, you confront this experimentation with two still life works composed in 1899, when the artist was 30. Matisse began his studies of art in Paris in 1891 after leaving behind a career in law, much to the dismay of his middle-class Normandy family. “Still Life with Compote, Apples, and Oranges” and “Still Life with Compote and Fruit” reflect his early efforts with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist techniques. The paintings nearly mirror each other in composition, but while the former experiments with an earthy palate, heavy brushstrokes, and geometrical shapes of a Cezanne composition, the latter is much more flat in color, the paint nearly translucent in its softness, fading away towards the left corner of the canvas, the colors nearly succumbing to the texture of the canvas itself. These two works could have been done by completely different artists, or at different times of an artist’s life. But here they are sitting together, composed in the same year, questioning any singular sense of Matisse.

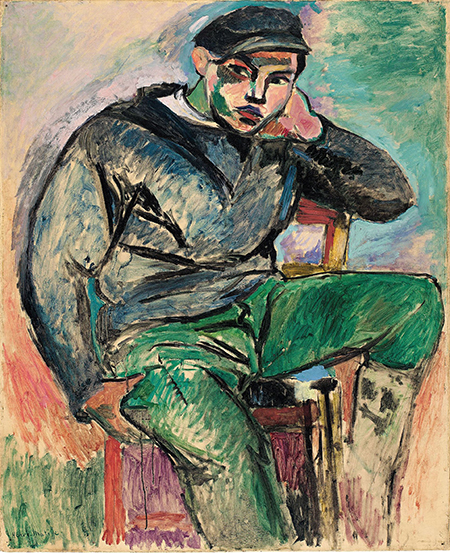

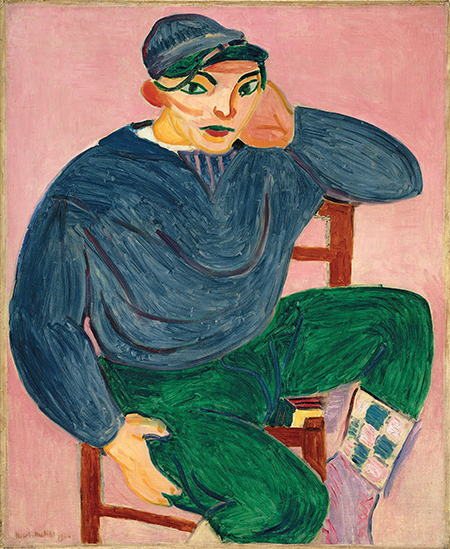

“Young Sailor I” (1906)

We confront this questioning again and again in this show, as these experiments with color and shape and perspective continue to challenge our sense of Matisse as more than that artist with the colorful collages. Consider “Young Sailor I” and “Young Sailor II,” each done in the south of France in 1906. The first canvas looks more like a sketch of paint, the sailor slouching on a simple chair, torso twisting to the left as he gazes off to the distance. The colors of both the sailor’s clothing and the background are roughly applied in quick brush strokes that reveal the canvas beneath, the body and facial features trimmed in black lines that are meant to give the subject some depth and solidity. The second version destroys the depth of the painting, presenting instead the shape of the sailor’s body defined with dark outlines and contrasting hues of green and blue and pink. The work lacks any sense of light or shadow — the sailor’s body looks nearly like a cut out of color shapes — and transgresses the pictorial perspective that was, in the demands of academic art, so crucial to what makes paint on a canvas a painting.

“Young Sailor II” (1906)

This loss of depth is clearly evidenced in his large canvases of “Le Luxe I” and “Le Luxe II” from 1907 and 1908 that hang nearby. Matisse uses the paint to give texture and shape to the bodies of the three women composed naked on a hillside, a lake and more hills rise behind them in the distant. But in the second version, the paint is there to give form, flat colors outlined in black, the shapes of clouds and hills flat and dense with brush strokes, the charcoal sketch underneath revealed through the paint. This painting evokes its very artifice as we encounter the artist’s efforts on the canvas, creating its own intimacy between viewer and artist, as well as viewer and canvas.

“Le Luxe II” (1907)

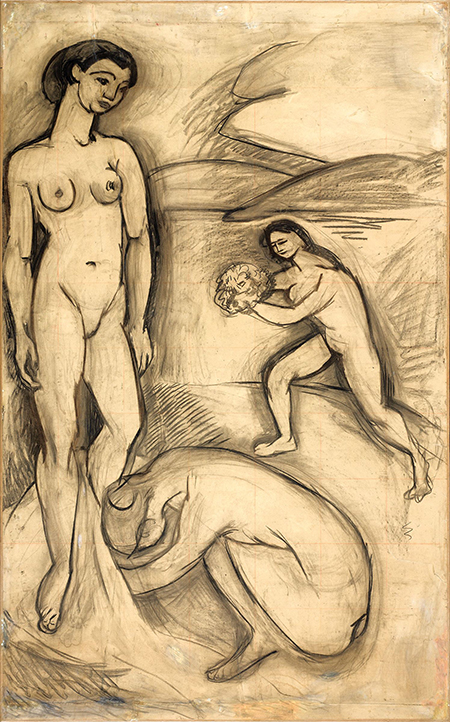

Alongside these paintings hangs a full-sized drawing of the first painting. Matisse commonly did sketches that were as a large as the canvases, believing in the power of the sketch to hold it own force in imaging the painting. Here the sketch serves to preserve the first painting, but also evokes the more reduced sense of depth in the second painting. This copying upon copying, a near obsessive mimetic exploration in the use of shapes and lines, underlines how the subjects of his paintings were increasingly less important than the how the canvas can present and hold the subject. In an interview from 1925, Matisse responded to critics who wondered about his repetitive subject matters arguing that throughout the history of art, painters “went on re-doing the same painting and always differently. After a certain time, Cézanne always painted the same canvas of the ‘Bathers.’” In evoking Cézanne, who he greatly admired, Matisse was aligning himself to a painterly process that emphasized the work of the artists as much as the subjects he created.

This process was itself a perpetual search into the limits and possibilities of not only paint but also the canvas itself. One wall text in the show quotes Clement Greenberg, the American art critic and champion of modernism, who wrote that Matisse was “a self-assured master who can no more help painting well than breathing.” This self-assurance rested on his ability at using the canvas as a field of exploration, of creating paintings that are caught in a moment of expression but utterly incomplete for both the artist and the viewer. There is a power in this incompleteness, as these works always seem to be in the process of becoming more finished. The force of such incompleteness raises a question that the show makes explicit about half way through: What constitutes a finished canvas?

Drawing for “Le Luxe” (1907-08)

For Matisse working and reworking a painting illuminated both the painterly process and the ongoing possibilities of the canvas. His early critics were distressed by this quality of his work. One critic in particular expressed his hope that Matisse would overcome this “malady of the unfinished” as if these sketch-like paintings were in some way a sickness. Perhaps as an effort to reply to such criticisms, Matisse began to photograph his painting process, and the transformation of the canvas through its stages of development, and continued to do so through much of his life. In his Notes of a Painter, published in 1908, he wrote: “I do not repudiate any of my paintings but there is not one of them that I would not redo differently, if I had it to redo. My destination is always the same but I work out a different route to get there.” In this way, the photographs of the works in progress offered a kind of road map as Matisse explored the direction of the painting each day.

“The Large Blue Dress” (1937)

By the 1930s the canvas itself became a dynamic space, for unlike his earlier focus on a series of canvases with a singular subject, he worked with the same canvas, painting and repainting it, scraping paint off from the last session, leaving other paint untouched, each reworking holding some trace of earlier compositions. This is how he composed “The Large Blue Dress” in 1937, painted over several days, each session concluding with a photographic portrait of the canvas take by a photographer who Matisse had hired. Helping him with this process was the model for “The Large Blue Dress,” Lydia Delectorskaya, a Russian émigré who met Matisse in Nice in the early 1930s when she was 22 and he was 62. Matisse hired her to be his wife’s assistant and to help him in his studio. While her presence caused a rupture in Matisse’s marriage (his wife left him in 1939), Delectorskaya would become his consummate model, muse and caretaker for the rest of his life. Throughout the 1940s Matisse and Delectorskaya, who was often his supportive collaborator in the studio, worked together in the painting process in his studio in Nice, almost unaware of the destruction of war that swirled around them. Matisse was not a political artist and his works from the 1940s have few traces of the conflicts of Europe.

Photograph documenting Henri Matisse’s of painting “The Large Blue Dress” (1937)

One of the last rooms of this show is a recreation of the Gallerie Maeght 1945 exhibition of Matisse’s works including “La France” (1939), “Still Life with Magnolia” (1941) and “The Dream” (1940). As they were in the fall of 1945, the paintings are displayed at the center of a constellation of photographs that evidence the process over the weeks Matisse worked on them. This was Matisse’s choice, to show the works in this context of development. The only point of the exhibition, Matisse wrote, “was to present the progressive development of the art works through respective states toward definitive conclusions and precise signs.” Oddly there is no mention of the war in this recreation of the gallery space, mounted just months after Germany surrendered and Paris was liberated. The city was still suffering from food shortages and limited electricity when the patrons crowded into the opening of the exhibition, encountering what must have seemed odd displays of paintings alongside their progressive stages documented in black and white photographs. Such a display offered a kind of film-like quality to the works, as curator Dorthe Aagesen notes in her catalogue essay, creating a series of photographic canvases that emerged into the one on display. But I couldn’t help but think that Matisse’s obsessions with preserving the painterly process were also a response to the destruction around him both personally and socially. The photographs as displayed with the paintings offer a marker of time and, within the historical context, conjured for me a kind of memento mori of each progressive stage, preserving each trace of creative effort at a time when so much was being lost.

“Still Life with Magnolia” (1941)

The preservation of his painterly process also allowed for a certain reality that art historian Jack Flam has described as a “perpetual state of becoming” suggesting how an emphasis on the artistic process allowed for its own continually unfinished project. And perhaps this is what makes this show so compelling. It reminds us that the labor of art is a layered endeavor that often gets mystified in our enthusiasm for the canvas as a icon of market value, distancing us from the complex artistic processes and cultural forces that determine when a canvas becomes painting.

Reprint of archival photograph documenting Henri Matisse’s process of painting “The Dream” (1940)

On the day before he died in 1954 at the age of 84, Matisse sketched a small portrait of Delectorskaya with a ballpoint pen. It would be the last sketch he would ever do. In her biography of the Matisse, Hilary Spurling notes that the artist held the drawing “out at arm’s length to assess its quality before pronouncing gravely, ‘It will do.’” • 18 January 2013