The 50 cent token set into motion the electro-mechanical magic of the batting cage. The magic is not in the conveyors, the wheels, or the accelerator arm which catapults hardballs dumbly into flight. It is the machine’s ability to pull special memories right out of the past and into the strike zone. To get the memories to dance among flying fastballs requires squinting a little at life and letting yourself be lifted with the suspension of the present.

Almost always in the cage, key moments of life’s turning points — especially the sharp turns into manhood — are there for the mental massaging, like the ritual rubbing of baseballs before the game. Many of my life’s pathways ran through baseball, and baseball ran like rivulets through my growing up in Carmichael, California.

The smells of freshly cut grass and dusty infields flowed out of memory as I swung mightily in the batting cage. I grunted and twisted with my bat; but the balls came whistling by, unimpeded by my 32-inch Louisville Slugger. They hit the canvas behind me with a dull thud.

A picture of myself 30 years earlier drifted out like smoke in the batting cage. I stood under the stadium seats at Edmund’s field, home of the 1950s triple-A Sacramento Solons. There, Nippy Jones, the Solons’ first baseman, was conducting a batting clinic for us Little Leaguers. He had selected me to demonstrate a technique in hitting off a batting tee. Thirty kids in dirty T-shirts gathered around me in a circle. After a few pointers, Nippy turned to me and said: “Okay, son, step up there and hit a few balls.” I was awed that he chose me. Time slowed. My mouth dried. I focused on the ball with an executioner’s gaze. I sent my hips into a forward-turning glide that had first caught Nippy’s eye. My body uncoiled, my little shoulders generating puny torque, arms extending into thrust. My bat whooshed through a forgiving volume of air, missing the ball entirely. Nippy Jones doubled over with laughter.

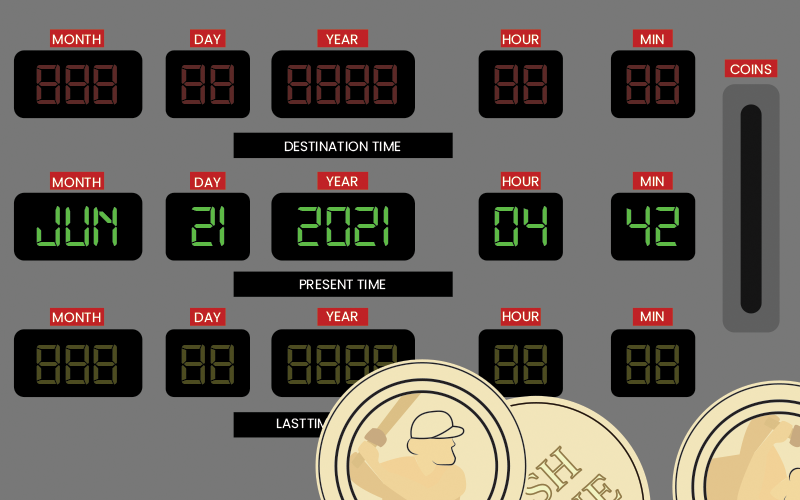

Back in the Myrtle Beach batting cage, I profited from this hors d’oeuvre of time travel. I readjusted my helmet, took a few deep breaths, and made an oblique connection sending the next ball spinning foul. A quiet ripple of hope lightened my mood. Anyway, I had hedged my bets. My pocket was heavy with machine tokens. I hit a few dribbling grounders and some pop-ups. Well before my tokens were gone, the mechanical imperatives of the swing — the proportional pacing of body levers and springs — were beginning to come back. This, in turn, elicited more memories, like the wiping of canvas with acetone resuscitates faded color from an aging portrait. Then, across a brief, imperceptible moment, I was off into the mists of history. The time machine was really beginning to hum.

Arching high up through a bright blue sky in memory, a small white speck reached a lazy apogee and began its descent on the far side of a right fielder. I was reliving a ball game my freshman year at UC Davis, playing on the JV team. The speck fell silently from view somewhere in the bleachers beyond the fence 340 feet away. Baseball was a great love, but definitely secondary to what I was being exposed to in the classroom. Only moments before seeing the sailing white speck, I left the on-deck circle totally engrossed in the day’s history lecture. At the plate, a blurry white ball came floating serenely toward me from a shadowy pitcher. This scene was framed by the molded plastic of my helmet and the out-of-focus profile of my nose. The rich crack of bat meeting ball snapped me out of the reverie on history. I was then startled to realize that the white speck sailing over the fence was off my bat.

It was an accidental discovery. My diversion back to the day’s history lecture had somehow sneaked me past my psychic sentinel, my Phantom Captain, who guards against my reaching outstanding feats in sport or anything else. I had learned in growing up that getting out too far in front of my dad was to step into troubled waters.

My dad’s early life was marked with grim struggle. A house fire destroyed the family farm. His father left the family to start over; the family unit never recovered. My growing up in the pastel ’50s unfolded in sharp contrast to my dad’s hardscrabble past. By the time I was in high school, we lived in a middle-class tract home. The specter of poverty never got near us. Yet, Dad worried that I wasn’t learning hard lessons the way he had learned them. Dad had a gruff, sandpaper exterior. Inside he harbored resentment toward my brother and me. A single anecdote summed it all up. After dinner one night at a fancy restaurant, Dad drew me aside, put his arm around me, and in a twisting motion, nearly threw me to the ground. “I could put you over so easily,” he said.

He was scornful of the breaking cultural revolution that sprinkled the country in the 1950s and showered youth in the 1960s. Dad was stern and sometimes resentful of our easy life, like an older species resenting the fresh colors of a new one.

My tentative overtures into the promising daylight of baseball were met with his skepticism. For me, it was convenient — less likely to elicit trouble from Dad — to simply not stand out too much. My internal survival mechanism, that force I call the Phantom Captain, kept me from coming into the unwanted glare of fatherly scrutiny. I generated extra measures of doubt about myself, and that helped to undercut any deliberate or accidental advance I might achieve in school, social relations, and, yes, baseball.

That’s why that home run was such a singular moment.

“You knew what was coming, right? You were you waiting for your pitch.” my roommate asked in a post-game celebration.

“Truth to tell, I wasn’t even thinking about baseball,” I confessed.

“Your head wasn’t in the game?”

“My head was far away . . . until I heard the crack of the bat . . .” I pictured the Phantom, asleep at the switch while I contemplated the history lecture in the batter’s box . . . “like it was an accident.”

•

In the previous year, my last year at high school, the Phantom had been relentless, making sure no such accidents happened. I was elected captain by my teammates and seemed to be on a promising path. Yet the Phantom lay at the ready to clamp down whenever a moment to shine drew near. In the last game of the season before going off to UC Davis, a good crowd with a sprinkle of big-league scouts saw my bid for fame turn into a bad dream. I made three errors, one a dropped ball on a first base cover play right in front of the scouts. Besides the errors, I went oh-for-three at the plate. My teammates were stunned. I was mystified.

The accidental breakthrough into home run hitting at Davis came the very next season. As was customary, UC Davis scrimmaged strong high school teams in the area. One game was with my high school alma mater, on the very diamond where the Phantom caused so much self-destruction the previous year.

The familiar diamond of my high school gave me a welcoming feeling. Perhaps because of my accidental success with the home run the previous month, I stepped to the plate with a lifting sensation of self-assurance. I hit the first pitch and saw it carry to the cyclone fence in right. It bounded off the fence for a double. My feelings soared a little higher. The next time up, I drove a low liner over the fence in right-center and into the ditch I once thought totally out of my reach as a hitter. I ended the day three-for-four, with the home run, a double, and a single. My former high school coach walked me back to the team bus. We shook our heads in disbelief once more, this time, sharing with me the irony of my day’s performance compared to the previous year on that field.

Many decades later, the time machine of Myrtle Beach let me see this history with fresh clarity. Tokens spent and muscles sore, I stepped out of the time machine and edged away from the cage in deep absorption. My children gazed up at my face. I felt that the look forming on my own face must have resembled the look on my father’s face during his many long, quiet reveries seated alone in a lawn chair during summer afternoons or at the beach, gazing off into the distance. Many times, I would come upon him in his deep absorption. I remember wondering then what was going through his mind. Now I guess he might have been chasing Phantoms, too. •