There has never been a better time to begin acquainting yourself with contemporary Chinese literature, and Megan Walsh’s The Subplot: What China is Reading and Why it Matters is an invaluable guide to that journey. It is a slim volume, but it is broad in its scope. It is focused on Chinese works published and read within the last 20 odd years, roughly speaking. It might be fair to say that, to the extent that English readers may be familiar with Chinese literature, the last few decades represent a cut-off of sorts. These recent years have seen an explosion in content that is overwhelming to spectators both inside and outside of the language. Yet they also have seen a sharp move away from any kind of simple political dichotomy which may have categorized many observers of Chinese culture before. This transformative state within the literature of the world’s most widely spoken native language is certainly worth all our analyses. Not least of all because gradually more and more content from China is finding its way into our daily lives, often without bringing with it a much broader social or historical context. This book is sure to result in both the finding of new content and new connections and facilitate a better understanding of exactly where today’s Chinese words are coming from.

For readers already familiar with some current trends, it will help contextualize their readings. To situate Liu Cixin’s popular The Three-Body Problem (soon to be a Netflix series) not only within a larger context of this so-called golden age of Chinese science fiction but to see alongside other patterns. Readers of Mo Xiang Tong Xiu will be interested to know how her three paperback New York Times bestsellers are properly situated within a larger context of danmei, largely homoerotic fantasy principally serialized for online consumption. Fans of Nobel prize winner Mo Yan’s absurd application of magical realism may find even more incongruence to contemplate in Yan Linke’s “mythorealism.” Youtube watchers who have run into the “cottage core” videos of Li Ziqi may be interested to read Jia Pingwa’s Broken Wings, a less-than-glamorous account of a young woman’s life in the countryside . . . or to learn of the Bishan Project’s attempt at constructing a rural utopia. Fans of China’s Sixth Generation filmmakers will likewise be interested in the “subaltern” literature (dicengwenxue) of professional writers such as Cao Zhenglu and the self-published migrant literature (dagongwenxue) of Chinese workers speaking for themselves. Above all, such a wide overview of what is being read in China today should serve as an indispensable tool in thinking about what connects all of these disparate elements.

Although under a hundred pages, Walsh ensures that her book is packed with the best examples of the multiple notable trends. Her analyses of each, though lucid, are brief. She acknowledges from the beginning that she wishes primarily for the authors’ words to speak for themselves. Yet a certain betrayal that risks reducing art to a social phenomenon is necessary in order to link all of her examples together. We start with the “post-80s generation,” a common term used to describe writers born in the 1980s, following China’s widespread market reforms, and occasionally used with dismissive or pernicious intent. We are introduced to perhaps the most emblematic of that group’s figures, Han Han, who climbed to the heights of celebrity as a controversial blogger and internet influencer. A dropout, Han Han has become a millionaire while vocally flouting the importance of the gaokao, the grueling standardized college entrance exam — nearly tantamount to flouting the Chinese government itself. After dropping out of school at age 17, Han went on to write a satirical novel about the Chinese education system entitled Triple Gate. The Chinese education system, he would write on his blog, is designed “to give the impression that people have no natural talent and get everything from education. That way, after you leave school, you will naturally accept that human beings have no inherent rights.”

The charges most often leveled against the “post-80s” writers, especially by older generations, is that they represent a kind of whiny, decadent narcissism brought on by market-driven individualism with little to no sense of social responsibility. Yan Lianke, an older writer whose works have found international acclaim and domestic bans, once said that the self-centered rebellion of the “post-80s” writers wasn’t rebellious enough, as “few of them can be heard when faced with social issues.” We could see the author and teen idol Guo Jingming as epitomizing such generational failures, with what Walsh describes as his “unironic tales of Shanghai’s vapid, wealthy youngsters, the so-called baifumei and gaofushuai — ’white, rich beautiful girls’ and ‘tall rich handsome boys.’” Such associations have led some “post-80s” writers to alternatively reject the title or to reject their generation’s literature itself (such as Yang Qingxiang). On the other hand, such a rejection of broader social dimensions has sometimes manifested itself in more innocent introspection. Walsh uses the example of the public fracas between elder poet Guo Lusheng and emerging “post-80s” poet Yu Xiuhua. In the ’60s, Guo suffered persecution during the Cultural Revolution and poetically protested the government’s usurpation of the individual in all aspects of life. Nevertheless, he expressed nothing but contempt for the younger Yu’s poetic musings on sex, consumption, and socializing. Yu fired back: “My fault lies in being on the bottom rung of society and yet still insisting on holding my head up high.” The irony of the two using such similar language to talk past each other is the kind of cultural incident normally indicative of a greater profundity yet to be fully understood.

Overall, we get a sense that “post-80s” writing could be a catchall phrase for class-conscious urban middle-class literature, and an equivalent of “lying flat” (tangping). Yet, as Yu Xiuhua’s example shows, it is too harsh to reject all the individualism and personal sentiment of this group, as the older generation of Chinese writers often do. Their personal accounts, far from representing condemnations of the struggles of pre-Reform generations, represent their questioning of the struggles that they are called upon to live through in the name of Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream. Walsh gives us this telling quote from Han Han, representative, perhaps, of the greater “post-80s” sentiment on politics:

Those people in the past, they simply found themselves cared about by politics whether they liked it or not, and the roles they played were just that of small fry, hapless victims swept around in the political currents of the day. Being a victim is no decent topic of conversation, any more than being raped has a place in a proper range of sexual experiences. The era when one can care about politics has yet to arrive.

One may read this as a form of bourgeois malaise. Yet it shows that, even for the upwardly mobile, and even within this new dream of economic prosperity, we have yet to arrive at a place where politics means anything (a feeling echoed outside of China, as well). If the “post-80s” writers show us that such privileged members of society question the value of their allotted tasks in China’s capitalist dream, the concurrent migrant worker poetry movement gives us the plaintive voice of the factory fodder of that dream. As Xie Xiangnan wrote in his “Orders of the Front Lines”: “My finest five years went into the input feeder of a machine / I watched those five youthful years come out of the machine’s / asshole — each formed into an elliptical plastic toy.” The sad story of poet and factory worker Xu Lizhi illuminates the movement so well that an English anthology and accompanying documentary on Chinese worker poetry borrowed their title from his poem “I Swallowed an Iron Moon.” In that poem, the young Xu tells us of his life, working at the notoriously abusive Foxconn factory in Shenzhen. There is no malaise here . . . Xu knows the source of his discomfort all too well: “I swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms / bent over machines, our youth died young [. . .] I can’t swallow any more.” Refusing to swallow anymore, Xu would take his own life a few months after writing those words.

If the previous trends are examples of a China which has lost its sense of direction — or at least lost faith in the official direction — then the technological dimension of today’s Chinese writing may hold the way forward. Just as Han Han began his ascent through blogging, the migrant worker poets used the internet to self-publish their words. In doing so they undercut the professional and often officially-sanctioned representations of workers delivered by the writers of “subaltern” literature. Yet the same technology which has confounded the traditional gatekeepers with its market economy has also quickly become a gatekeeper of its own content.

According to Walsh, online reading platforms such as China Literature and Qidian are reported to have 430 million currently active readers and are “touted as China’s most realistic shot at exerting cultural soft power.” Yet, says Walsh, “the millions of online novels that are being churned out seem proof that, despite government narratives emphasizing core socialist values, mainstream culture is governed by the mercenary, amoral instincts of the market.” More and more, however, these 24 million or so novels are not representative of any one author’s vision but are the product of anonymous laborers who are forced to “hammer out between 3,000 and 30,000 words every day.” Responding to demand as quickly as possible, this literature has been dubbed yiyin, or “lust of the mind,” with very shallow content driven by short-term gratification and ego-boosting. A subgenre known as xianxia, or “immortal hero,” centers around a masculine hero who flawlessly ascends from a lowly status through video game-like levels of challenges, all while retaining childlike pettiness . . . its consumers, diaosi, apparently a Chinese equivalent to incels. Despite the government’s growing misgivings over online literature, such a genre is really the embodiment of the official “Chinese Dream” ideology. “Online characters don’t change anything but their circumstances and status,” Walsh tells us. That describes the cutthroat mental state that the young urban Chinese find themselves in pretty well.

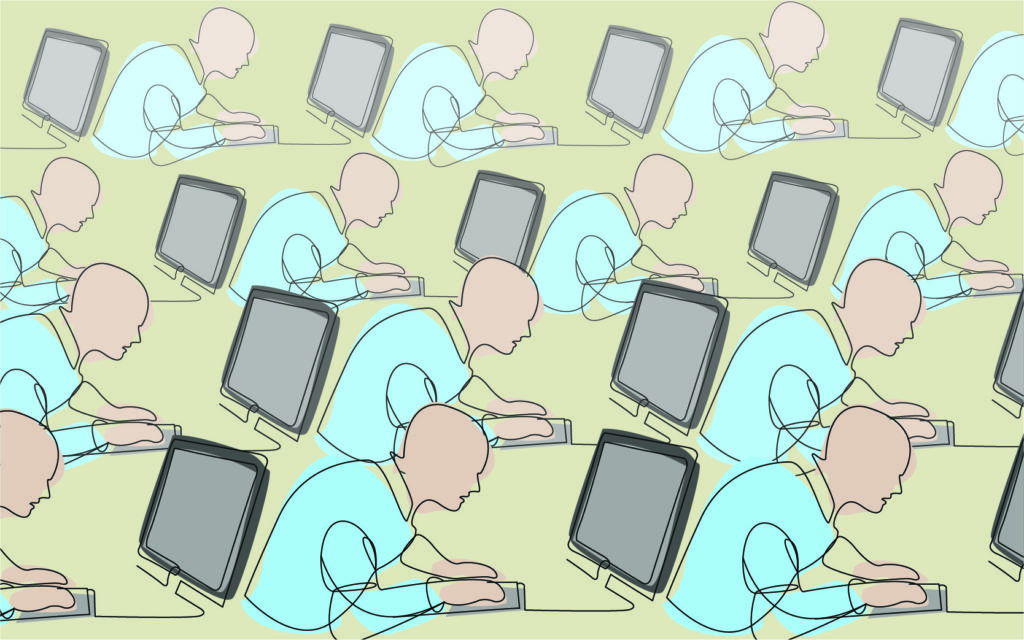

Perhaps themselves the product of urban middle-class ambitions to escape industrial labor, the sad fact about these anonymous online writers is that they are “re-creating the conditions of the factory, chained to their computers, hammering out thousands of words each night after work, manning virtual production lines in which supply can’t meet demand.” Walsh adds that “like manual workers in many other industries, many jobs may soon be destroyed by automation.” Artificial intelligence is already being employed in Chinese fiction. Walsh recounts the chilling instance of Chen Qiufan’s short story “The State of Trance”, which featured computer-generated text such as:

But this begins with the turn of the real mathematical power, it is very hard to lose the afterward, to change the future’s website, as well as assisting the surface of ceremony, pretending that it is somewhere concealed, but can only face crowds.

An authentic tumor.

In 2018 Chen’s piece was one of thousands in an AI-judged literature competition, where it came in first place . . . demonstrating that one algorithm was able to identify the work of another and show preference for it. Do the words mean anything? If the online fiction market shows us anything, it is that there is a huge market for shallowness that hits all the right algorithmic points. With the purchase of China Literature by Tencent, “the world’s largest gaming and social media company,” in 2020, this future is certain. The multinational conglomerate has made it clear that applying AI across various industries is a key part of its mission. If we take China Literature’s motto, “Live your dreams, don’t waste your youth,” next to Xie Xiangnan’s poetic lament of seeing his “five youthful years come out of the machine’s asshole,” we get perhaps the clearest possible image of the state of today’s Chinese literature. No great clamor for democracy and freedom as such. The control and propaganda of the government aren’t necessarily as pernicious as those of the market. “Xuanchuan,” Walsh indicates, means both propaganda and publicity.

On the point of government control, Walsh wishes to indicate that some of our valuations of Chinese art are flawed. She highlights Salman Rushdie’s labeling of Mo Yan as a “patsy of the regime” as such a poor valuation. “The assumption can be that those who don’t openly challenge China’s authoritarian system from within are apparatchiks, not artists,” she says, “But the fact is that most Chinese writers who continue to live and work in mainland China write neither what their government nor foreign readers want or expect.” She goes on to add, recalling the intrusion of oikosinto polis at the heart of Sophocles’ Antigone: “And in our failure to engage with and enjoy Chinese fiction as it is, in all its forms, we misunderstand our own part in the complex and often fascinating realpolitik at its heart: this intrusive relationship between grand and personal narratives.” This is a brilliant and necessary observation from Walsh, who uses for example Yu Xiuhua’s poem “Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You,” which was criticized for its blatant individualism. An interesting counter-argument, however, is later provided by Uyghur poet Tarim: “Friends say / the beauty of Chinese / is its subtlety / I ask / Is that because there is no freedom of speech?” Perhaps recapturing the language from such self-serving “subtlety” implies a higher loyalty to serving the self in writing. Perhaps this generation’s Antigone and struggle is exactly the open challenge that the spectator has been predicting. If so, then Walsh is correct, we definitely are missing out.

Some other very important takeaways from the work are its observations on censorship, changing generational norms, publishing technologies, and artificial intelligence. Censorship works through a combination of unpredictability (the “anaconda in the chandelier”) and pragmatic targeting. The more widely consumed a media is, the more likely it is to be scrutinized. This leaves significant freedom in more intellectual segments of society. Modern Chinese art is no stranger to generational differences, as evidenced by the nomenclature of its cinematic “generations.” Yet the rift between the “sent-down youth” generation of the Cultural Revolution, sent to the countryside to work, and today’s “lying flat” youth, rejecting the state-promoted rat race, could not be much greater. As the largest post-industrial explosion of Chinese literature is underway now in the digital age, it has become apparent that the role of purely digital publication means will be pivotal for the future of publishing everywhere — and physical media, much less so. The ability of the internet to both facilitate the telling of lesser-heard stories and to reduce art to its lowest common denominator is both promising and frightening. While migrant workers, ethnic minorities, and other voices have been given wings through the digital medium, we are also seeing a shift toward influencer-based literature and literature produced in conditions reminiscent of sweatshops. Finally, we must pay very keen attention to the developments around AI in literature as the above-mentioned literature industry becomes automated. AI literature is definitely only going to grow in prominence, regardless of the deeper artistic or philosophical quality of its work.

If there is any fault to be found, it is not in the book itself, but in the way that it was promoted. Columbia Global Reports, and the author herself, seemed too eager to pitch the work as a remedy to widespread ignorance. Such ignorance is more a projection of their pasts than a reality of the present. As Jeffrey Wasserstrom said in the first episode of Columbia Global Report’s Underreported podcast promoting the book, 20-somethings in the US and China have much more in common than ever before — and they know it. Stories about adventurous youngsters visiting China in the ’80s and going on to spend their lives combatting Western ignorance ring absolutely hollow in today’s world. The hundreds of thousands of international tutors participating in the China-based billion-dollar online English education industry in the 2010s-20s had over five years of intimate contact in Chinese living rooms (despite the 2021 ban on foreign teachers online, many Chinese parents continue to seek them out). Online gaming, the success of The Three-Body Problem among sci-fi readers, and the enormous presence of Chinese students on Western university campuses all put millennials in an extremely different position than Walsh herself must have been in those formative years. I myself, an older millennial readily recall Chinese classes at school, Chinese movies on streaming platforms, and Hollywood infamously beginning to kowtow to political pressure from Beijing.

All these things hit too close to home for a reading of Walsh’s book which holds that it is dispelling some thick, culturally biased ignorance. That, in fact, sounds exactly like the kind of line that Xi Jinping likes to take these days, endlessly insisting on the profound and irreducible chasm between China and the rest of the world. Where does he get such language from? Putin gets his from us. For our part, we have also announced our allegiances to “alternative facts.” This is the “inward-looking” at the heart of the Liu Cixin quote that Walsh gives us, about a dystopia in which both human happiness and ecological stability are preserved, but only at the cost of all human freedom. The alternative approach, “outward-looking”, would entail continued perpetual human intervention in the world. It would also, however, imply objective judgments on that world, including on its governments. It is sad to see The Subplot promoted in a paradigm that is so “inward-looking,” criticizing Western biases when the thrust of the best works described are very much not in such a direction.

Walsh provides us with a quote from Xia Jia on the Chinese-ness of Chinese science fiction: “The Chinese had to wake up from their old, 5000-year dream of being an ancient civilization and start to dream of becoming a democratic, independent, prosperous modern nation-state.” If that is so, then the importance of much Chinese science fiction today is its outward-looking, not as some method to evade censorship or provide an escape, but literally as a way to imagine a future . . . something besides so-called “capitalist realism.” Discontent with such bleak realism can be found within the migrant worker poetry movement in particular, as Christian Sorace has noted: “Chinese workers live under the paradoxical condition in which their emancipation was declared to have been achieved, which forecloses its possibility in the future. As a result, their lives are suspended in an eternal present of capital accumulation dressed up in socialist garb.” Opening that imaginary future — much more than mere censorship evasion — is the most fascinating cultural labor being undertaken in China today.

The reality is (and Walsh observes this in her book) that Chinese popular culture is moving closer and closer to Korean or Japanese popular culture every day, demonstrating the truth in Bong Joon-ho’s observation that today, “we all live in the same country, called Capitalism”. It may have been surprising to a young future-China expert in the ’80s to see Mao watches for sale outside of his mausoleum, but my generation wouldn’t blink at the suggestion. We know China too well for that. That being said, we should also be deeply grateful for this volume from Walsh, the aforementioned promotional angle aside. Given that we are encountering China in many different ways today, we are not necessarily understanding the broader Chinese experience. Specialists, in particular, are liable to suffer from such blind spots, where a literary assessment might exclude or denigrate genre fiction. Walsh’s work isn’t a success because it is specialized, but specifically, because it isn’t. It is generalized, and it is about a part of the world with which a global general audience is increasingly familiar. Only in that specific way can we say that Columbia Global Reports has hit the mark in its effort to bring out works covering subjects neglected by “conventional news coverage” . . . only in the sense that conventional news coverage would prefer to continue to exoticize that which the average person already has an increasingly intimate connection with.•